CYCLING THE KARAKORAM HIGHWAY

From China to Pakistan, on the world’s highest road

Continuation of the adventure ” Kyrgyzstan, immersion in the life of Kyrgyz nomads “.

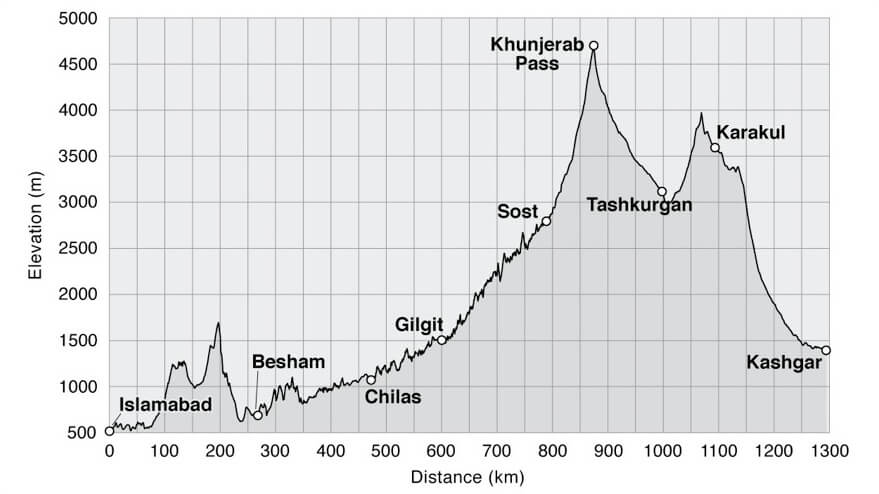

The Karakoram Highway is a road in the heart of Asia, the only link between China and Pakistan. Largely asphalted and culminating at an altitude of almost 5,000 m, it is the highest motorable road in the world. 1,300 km long, it links the Chinese city of Kashgar to Islamabad in Pakistan.

Profile of the Karakoram Highway. I travelled from Kashgar (on the right) to Islamabad.

After Chilas, I took another section of the Karakoram Highway over the Babusar Pass, 4,173 m above sea level.

I love traveling by bike. It’s a humble means of locomotion that resonates with everyone. Whether you’re Chinese, Bolivian or Ethiopian, everyone has ridden a bike. Everyone knows the effort it represents and the freedom it brings. With my pannier-laden luggage rack, my mount intrigues and invites exchange. But above and beyond facilitating encounters, what I prefer most about cycling is the gentle slowness of the journey. At 20 km/h, you have time to really soak up a landscape, the relief of a mountain or the scents of a forest… something that car travel doesn’t fully allow. Sheltered from the wind, rain and cold, the passenger compartment puts a protective distance between the traveler and the region he’s passing through. When it comes to time, terrain and distance, speed is arrogant. Conversely, when detached from the clock, slowness is conducive to contemplation.

This is the story of a 5-week cycling adventure through the Karakoram mountain range, between heaven and earth in one of the most hospitable nations on the planet.

China

Border post between Kyrgyzstan and China. It takes me 7 hours to cross from one country to the other. Firstly, because Chinese immigration is 130 km inside the country, and I have to get into a minivan to get there. Secondly, because of the slowness of the customs agents who inspect all my belongings. I have to X-ray them three times.

For this 5-week bike trip I decided to pack light to make the climbs less strenuous. Here’s what I packed.

BIKE: Surly Long Haul Trucker, 2 inner tubes, patches, multi-tools, pump, helmet, turnbuckle, 2 Ortlieb Back-Roller Classic panniers, Vaude handlebar bag, flex clamps

ELECTRONICS: Canon 6D, 50 mm lens, 24-105 mm lens, 5 SD cards, Rode external microphone, tripod, remote control, external hard drive, MacBook, batteries, chargers, headphones, iPhone

CLOTHING: shorts (never used, the Brooks B17 saddle is even more comfortable without shorts), windbreaker, shorts, shirt, t-shirt, technical tops and bottoms, hiking boots, 2 pairs of socks, cap, fleece, 2 pairs of boxer shorts, sunglasses, Buff, gloves.

CAMP EQUIPMENT: sleeping bag, ground sheet, bivvy bag (replaces tent), headlamp, Swiss Army knife, Spork, canteen, Esbit stove with ultra-light refills, lighter, soft backpack, zip-locks

HYGIENE: toothbrush, toothpaste, hard soap, microfiber towel, sun cream

OTHER: passport, 2 credit cards, cash, pen

The Id Kah mosque is the largest in China. It is located in the city of Kashgar in the far west of the country, in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which has an overwhelming Muslim majority.

The old town is a maze of quiet little streets.

At the end of the school day, some do their homework…

…while others prefer to play.

For 2,000 years, Kashgar has been the meeting point of the various Silk Roads. The city lies at the crossroads of the Taklamakan desert to the east and the Pamir mountains to the west. In the past, caravanners came here to trade their yaks for camels and vice versa. Even today, Kashgar’s main activity is trade.

First turns of the wheel on China’s Karakoram Highway. From Kashgar, 413 km separate me from the border with Pakistan.

The road winds through the mountains. At this point, I still have 230 km of climbing to do before I see my first descent.

On the way, I pass by Bulunkou lake, which offers a superb panorama of sand dunes. Unfortunately, it’s strictly forbidden to go walking there. Xinjiang is an autonomous province with a special status, like Inner Mongolia or Tibet. It is subject to numerous community tensions, and the government tries to keep it under wraps to prevent any attempt at revolt or independence on the part of the Uyghurs. The province is heavily militarized, with numerous checkpoints.

I’m very pleasantly surprised by the courtesy of the Chinese truckers. They never honk at me and always leave plenty of space between them and me when overtaking.

Karakul Lake in Xinjiang, where I’m trying to find accommodation in a yurt or camping.

After a grueling day, I try to sleep in a yurt at Karakul Lake. This is a destination where many Chinese tourists camp at weekends. Unfortunately, the nomads tell me that, unlike last year, they are no longer allowed to welcome foreigners. Knocking on every door, the police notice me and tell me I’m not allowed to be here without a guide. After 2 hours at the station, it turns out that I’m not allowed to sleep in the area and have to go to Tashkorgan, 90 km from the lake! The region isn’t dangerous per se, but the Chinese authorities take a dim view of foreign tourists in Xinjiang. I offered to sleep in the barracks, but the police refused. At 8pm, the police throw me out without offering me a solution. Exasperated, I got on my bike and hid out to camp at the first opportunity. Without a tent, I spend a chilly night in my bivvy bag, hidden behind the wall of a telephone relay antenna.

One of the last climbs before the town of Tashkorgan in Xinjiang. With the exception of a handful of Tajik and Chinese trucks, I’m alone on this stretch of road. At almost 4,000 m, I stop regularly to enjoy the view.

The fortress of Tashkorgan. In the Uyghur language, “tash kurgan” means “stone fortress”. This is where my road to China ends. The Chinese authorities won’t let anyone take the road to Pakistan on their own. The only solution is to board an official bus with a guide.

Pakistan

The Khunjerab Gate seen from the Pakistani side. Inaugurated in 1982, it marks the border between China and Pakistan. At an altitude of 4,693 m, it is the highest open border crossing in the world. Due to snow conditions, the pass is closed from November 30 to May 1.

The descent from the border is vertiginous. After several days of non-stop climbing, it’s a liberation to let go and head into the valleys of the Hunza region in northern Pakistan.

The Karakoram mountain range abounds in glaciers. In summer, they feed the Hunza River and the current becomes extremely powerful.

The Hunza valley is surrounded by several 7,000 m peaks.

Attabad Lake. It was formed in 2010 following a gigantic landslide that engulfed several villages and a 19 km stretch of the Karakoram Highway. 6,000 people were displaced and several villages wiped off the map. Today, the lake is over 21 km long and 100 m deep. For many years, the road was cut off and vehicles had to be put on barges to cross, but today the Chinese have built tunnels through the mountain and traffic has resumed.

The Pakistanis give me an extraordinary welcome. Everywhere I go I’m greeted, smiled at and asked about the reasons for my visit.

I drive along the Hunza River, a beautiful green road. In the valley grow many apricot and cherry trees, whose fruit is sold along the roadside.

Inside the royal fort of Baltit in Karimabad. The fort is a former royal residence dating from the 12th century, overlooking the entire valley.

A man in traditional Pakistani dress, wearing a “topi”.

The village of Karimabad is perched high in the mountains, offering exceptional views over the Hunza valley.

In Karimabad, a group of Pakistani tourists visit Baltit Fort. Pakistani society is still very much male-dominated. It’s rare to see a group of women in the street, or to make any real contact with them.

Sunset over the Karakoram mountain range. This massif boasts a high concentration of glaciers and peaks, including K2, the world’s second-highest mountain (8,611 m).

I head south again, still following the Hunza River.

Pakistanis are generally quite fond of photos. Often in the countryside, it represents a solemn moment for them, and it’s difficult to make them smile.

A scene of daily life at the end of the day in the streets of Gilgit. Gilgit is the largest city in northern Pakistan and serves as a tourist hub for all mountaineering expeditions in the Karakoram.

I love taking portraits of people I meet. I always ask permission, but sometimes complete strangers spontaneously ask me to take their picture. This is the case here, where I took the photo of this boy selling cherries in the Gilgit market.

I’m stopped by the police just before the town of Chilas. I’m entering a rather tense region that is the subject of a number of inter-religious tensions. It’s also the region where 9 foreign tourists had their throats slit by terrorists in 2013. The situation is now stable and under police control, but I’m not allowed to continue my journey alone. I have to ride with a police escort.

A police car follows me for a hundred kilometers. It’s very frustrating to be followed and to suffer the impatience of the policemen, who are in turn frustrated by driving at 25 km/h, but as time goes by we get on well.

After the town of Chilas, I have a choice of two routes to Islamabad. One is relatively flat but longer (the one shown in the graphic at the top of this article), while the other is shorter but much more mountainous. The second route being the more spectacular, I chose this option.

After a grueling 9-hour climb, I reach the summit of the Babusar pass at 4,173 m altitude.

It’s the hardest climb I’ve ever done. I set off in the morning from Chilas, which lies at an altitude of around 1,000 m, and arrived at the pass at 4,173 m in the evening. 3,000 metres of ascent in a day’s cycling isn’t so difficult in itself, but what was really tough was that the climb was only 40 km long. The gradient of the road was often in excess of 12%, and it took me 9 hours to complete it. Sometimes climbing at a speed of 4 km/h, 7 police cars took it in turns to escort me. At every break, the policemen insisted that I put my bike in the back of the pick-up. Faced with their dumbfounded looks, I resolutely refused all their suggestions.

Nowhere else have I been asked to take so many selfies. Since my arrival in Pakistan, the locals have paid me a lot of attention and it’s impossible to go unnoticed. I’ve posed for photos around fifty times a day. When I’m driving, cars often come up to me to talk to me and sometimes stop in front of me to shake my hand. It’s very touching to feel so welcome, but sometimes I have to take it in my stride when people are so insistent.

At the top of the Babusar pass, temperatures at night drop below 0°C. After a long negotiation, I finally find refuge in the police station. Before going to bed, an official makes a radio call to the police teams at the various checkpoints.

When I arrived at the pass at an altitude of 4,173 m, the chief of police was furious at my late arrival. Apparently, he had asked each of his colleagues to make me get into the cars escorting me. Faced with the chief of police’s aggressiveness – which is actually quite zealous – I choose to be completely indifferent to him. He forbids me to sleep on the pass. The Xinjiang scenario in China repeats itself, except that this time the road down south passes through communities that are quite hostile to foreigners and where stopping is strongly discouraged. As night approaches, I have no option but to stay close to the police. Tempers flared and the situation became tense. On my travels, I’ve always been able to manage my relations with authority figures such as customs officers or policemen: a pinch of bluff mixed with a good dose of humor has always enabled me to extricate myself from tricky situations or attempts at bribery. But with my overexcited energetic self, I have to be very diplomatic to make my case. After 4 hours of mutual obstinacy, I finally obtain the right to stay in the police barracks for the night.

“Be careful, here people have nothing, they cut your neck!”

The next day, I quickly descend to the other side of the Babusar pass. I know that some of the communities here are not very welcoming to foreigners. Even the Lonely Planet reports that tourists are sometimes pelted with stones, but generally speaking the security situation is stable and the police are very present. However, I can’t shake off the conversation I had the day before with a Spanish tourist traveling with her guide for the 4th time in Pakistan. Surprised to see me alone, she told me in French before leaving: “Faîtes attention, ici les gens n’ont rien, ils vous coupent le cou!”. I took it with a smile, but it’s true that I didn’t linger too long on the road.

Gittidas, the village where you shouldn’t have stopped. As I took this photo, voices rose up from the village. Children started running towards me with a few adults behind them, one brandishing what looked like a pitchfork or shovel. In 5 seconds I put my camera away and with my heart pounding I ran 5 km at full speed.

I pass by Lulusar lake, where a soldier takes advantage of a break to make a phone call.

The Kaghan Valley is a beautiful green valley where villages are concentrated along the river. Travelling alone, I’m often asked how I manage to take this kind of shot. While I sometimes hand my camera to strangers to take a quick photo, I also take the time to set myself in a sublime landscape. To take this photo, I first set up my camera on a tripod with an automatic shutter release every 2 seconds, then run to my bike, mount it, and run back to stop the automatic shot. I start again if I’m not satisfied with the result. All in all, a photo like this takes me about 30 minutes of work.

I spend a little time with these 4 men who called out to me as I rode by on my bike.

Children crammed into a truck on their way to the Babusar Pass in the early hours of the morning.

I stop for lunch at a roadside restaurant. For 200 rupees (€1.60) I eat a delicious beef curry with naan and tea. At the end of my meal, a group of Pakistanis join my table and invite me to share their dishes. I have lunch again.

On the way to Islamabad, I pass many families sitting on the side of the road.

At the top of a hill, I stop next to this man. He wears a keffiyeh, a large blanket over his shoulders, and clutches a long stick in his right hand, which he uses like a walking stick. He questions me insistently in Urdu, speaking slowly and mincing his sentences as if to make it easier for me to understand. But I don’t understand a word. Thanks to sign language, however, we manage to communicate and even laugh.

Passing through a small village, I stop to take a few photos. This man, intrigued by my presence, walks over to me and shakes my hand. Showing him the portraits I’ve already taken of other people, he agrees to play along.

Meet a young boy waiting for a car to take him to the town of Naran.

“Welcome! What’s your name?” As I was looking at my iPhone to see which way to turn at an intersection, a smiling Pakistani approached me. Safir is 35 years old, he worked for the American army in Kabul for 5 years, but since the Americans left Afghanistan, there’s been no work and he’s returned to Balakot, his hometown, to look for a job.

My cycling route is drawing to a close, the mountains are behind me and the city of Abbottabad is holding out its arms to me. The temperature has risen, and I’m tired but happy with the effort I’ve made.

In a pine forest, I pass a group of Pakistanis loading hay onto a truck.

This photo, taken in Abbottabad, marks my arrival at the end of the Karakoram Highway, after 1 month on Chinese and Pakistani roads. From here, I’ll be taking buses first to Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, then on to Lahore, the historic city some twenty kilometers from India.

In Abbottabad, I visit the site of Osama Bin Laden’s former fortified compound out of curiosity. Not knowing exactly what to expect, I had scouted the geographical coordinates to find the exact location of what was once the home of the world’s most wanted terrorist. A few months after the assault by American special forces in May 2011, the Pakistani army totally destroyed the complex. Today, almost nothing remains, but the land is open and serves as a playground for local children.

The Badshahi Mosque in Lahore is an architectural gem. Built in 1673, it remained the world’s largest mosque until 1986, when it was dethroned by the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. When I arrived in Pakistan, I met Raza, a 22-year-old boy. We quickly hit it off and arranged to meet in Lahore. Welcomed like a king, I spent four days with Raza, visiting Lahore and meeting his family and friends.

Because of the conflict surrounding the partition of Kashmir, relations between India and Pakistan are extremely stormy. The only crossing point between the two countries is at Wagah, where a ceremony is held every evening by both sides, amid electrifying patriotic fervor.

The border guards, after adopting various postures and attitudes of defiance towards each other, finally join together to shake hands and close the two gates that materialize the border.

On my last evening in Pakistan, I sip tea with Raza from the terrace of a restaurant overlooking the Badshahi mosque.

Off to India! Since India and Pakistan rarely issue visas to each other, the border post between the two countries is virtually empty. I cross the border alone at Wagah, heading for Amritsar and then Ladakh, where I plan to meet up with my friend Nicolas for a Royal Enfield adventure (see the adventure “Ladakh by Royal Enfield”).

The Karakoram Highway, also known as the “Friendship Highway” to the Chinese, lives up to its name. The Pakistanis gave me an extraordinary welcome, and I experienced their incredible kindness and generosity on a daily basis. While it’s true that the region around Chilas requires a few precautions, the rest of northern Pakistan is not as dangerous as you might think. Quite the opposite, in fact, and I can’t wait to go back.

Read more about the adventure ” Ladakh by Royal Enfield “.