SOUTH POLE OBJECTIVE

A French first and a world record in Antarctica

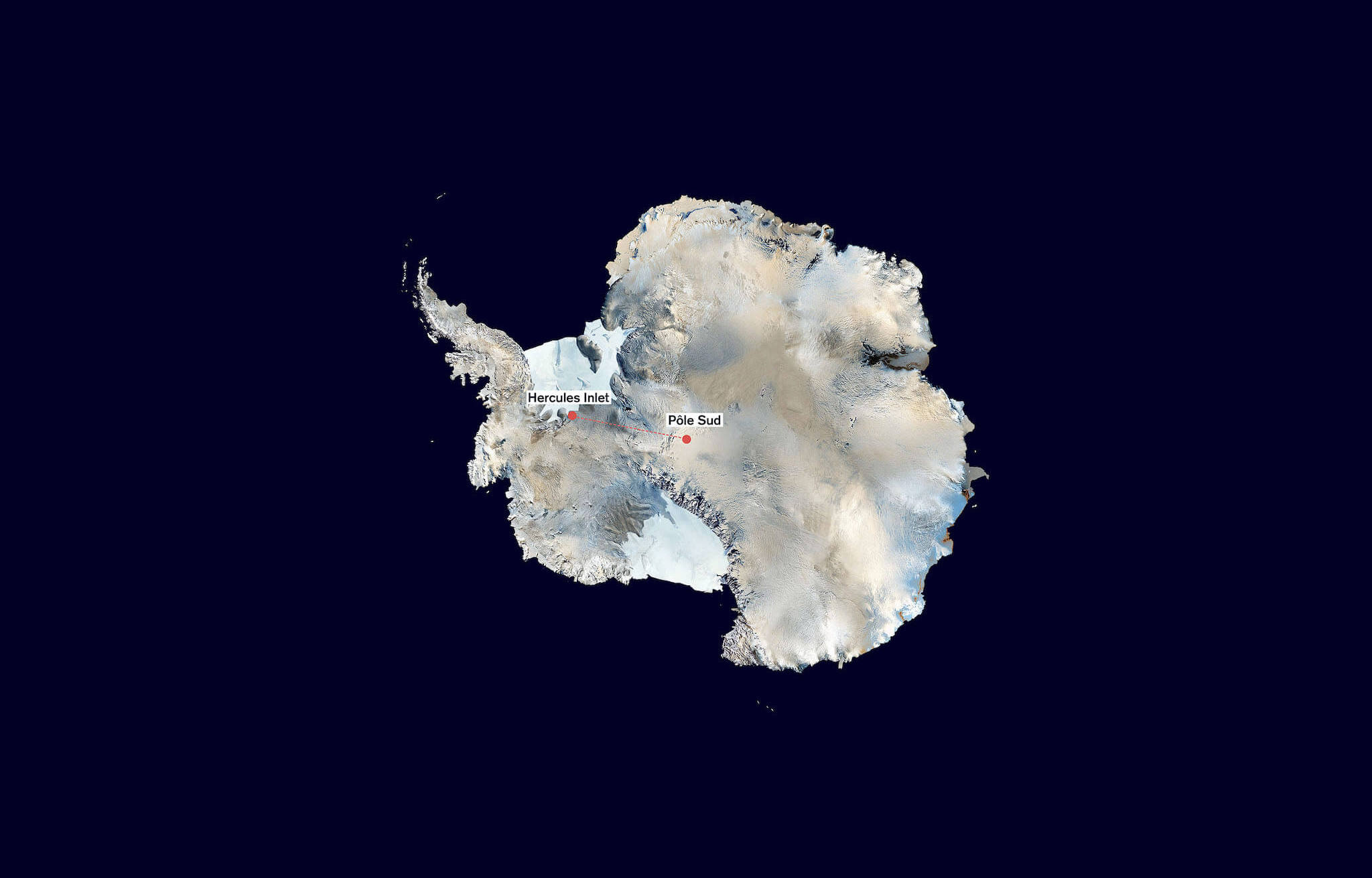

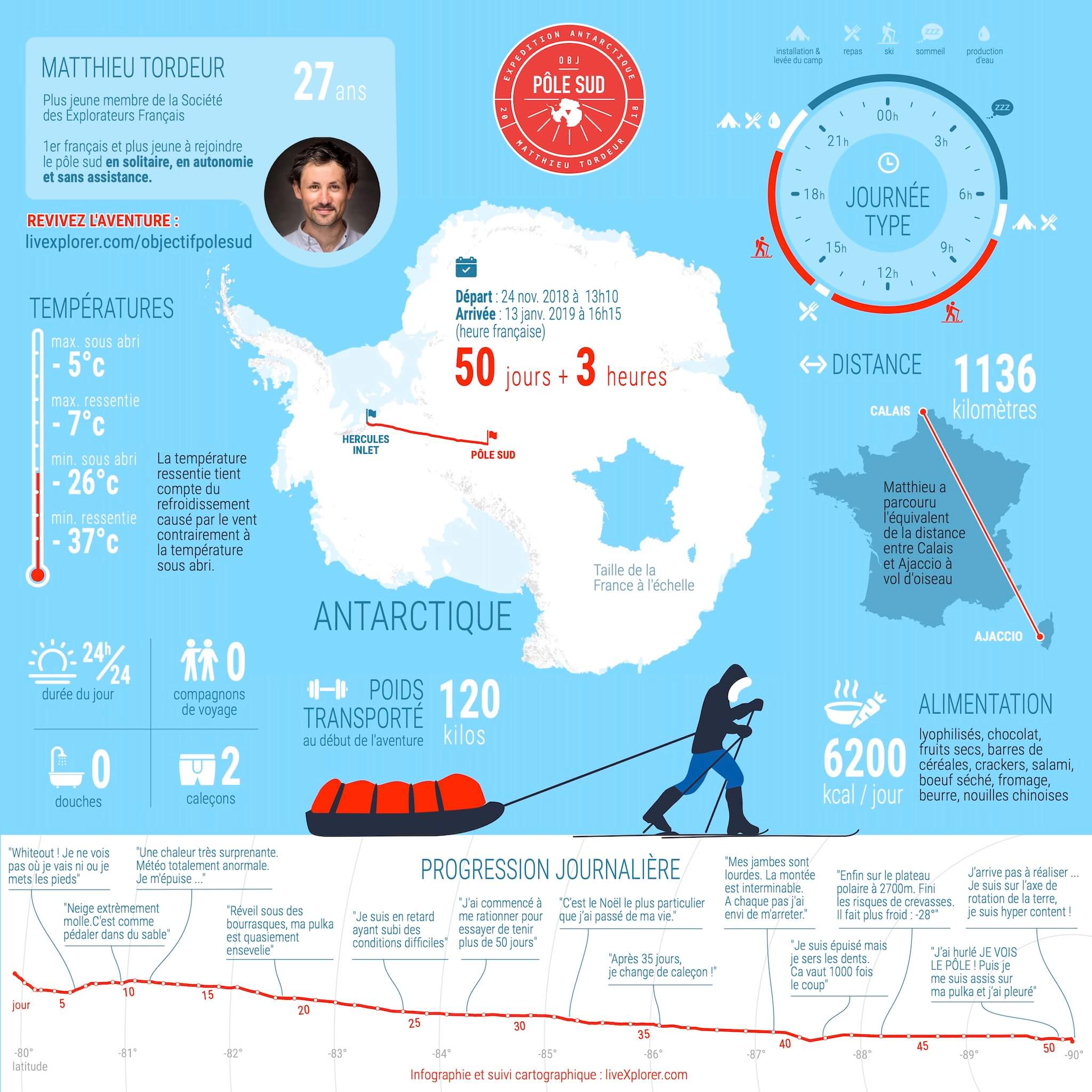

It all began with a dream. To travel part of the White Continent, a land of exploration and discovery. The playground of polar explorers like Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton, Charcot and Victor… Ever since I was young, I’ve been fascinated by the courage and self-sacrifice of the heroes who made Antarctic history. Just over 100 years after Norway’s Roald Amundsen discovered the South Pole, I decided to take my turn in the polar adventure. My idea is simple: to reach the geographic South Pole from the coast of the Antarctic continent. A journey of 1,150 kilometers, the distance between Ajaccio and Calais.

I’m going on this expedition alone. I want to experience real solitude. The kind that never lets you go and brings you face to face with your worst doubts and worries. But it’s also the kind that reveals you to yourself and allows you to discover something new, unknown and unsuspected. I’m not a solitary person by nature, only the experience of solitude interests me. It’s conducive to introspection and contemplation.

I’m leaving unsupported. In an age when technology allows us to be at the other end of the planet in 12 hours by plane, I want to experience slowness, to establish a new relationship with space and time. So I set off on skis, without traction sails, sled dogs or motor vehicles. I rely solely on the strength of my legs and my desire to go all the way. I’m not one of those people who leave to run away from something; in my adventures, I like the departures as much as the returns. But in a world of immediacy and instant gratification, I want to slow down, to take a step aside. So I set off in total autonomy, relying solely on myself. No flora or fauna on the route. The heart of Antarctica is a permanent freezer where no animal or plant species can survive. In my sled, I carry 50 days’ worth of food, gasoline to melt the snow and obtain water, camping equipment, technical clothing to withstand temperatures of -50°C… No food supplies are planned on the route, and I have to pull all my provisions with my own strength – 115 kg, more than one and a half times my own weight. It’s a daunting task, and as proof, only about twenty explorers in the world have ever managed such an expedition.

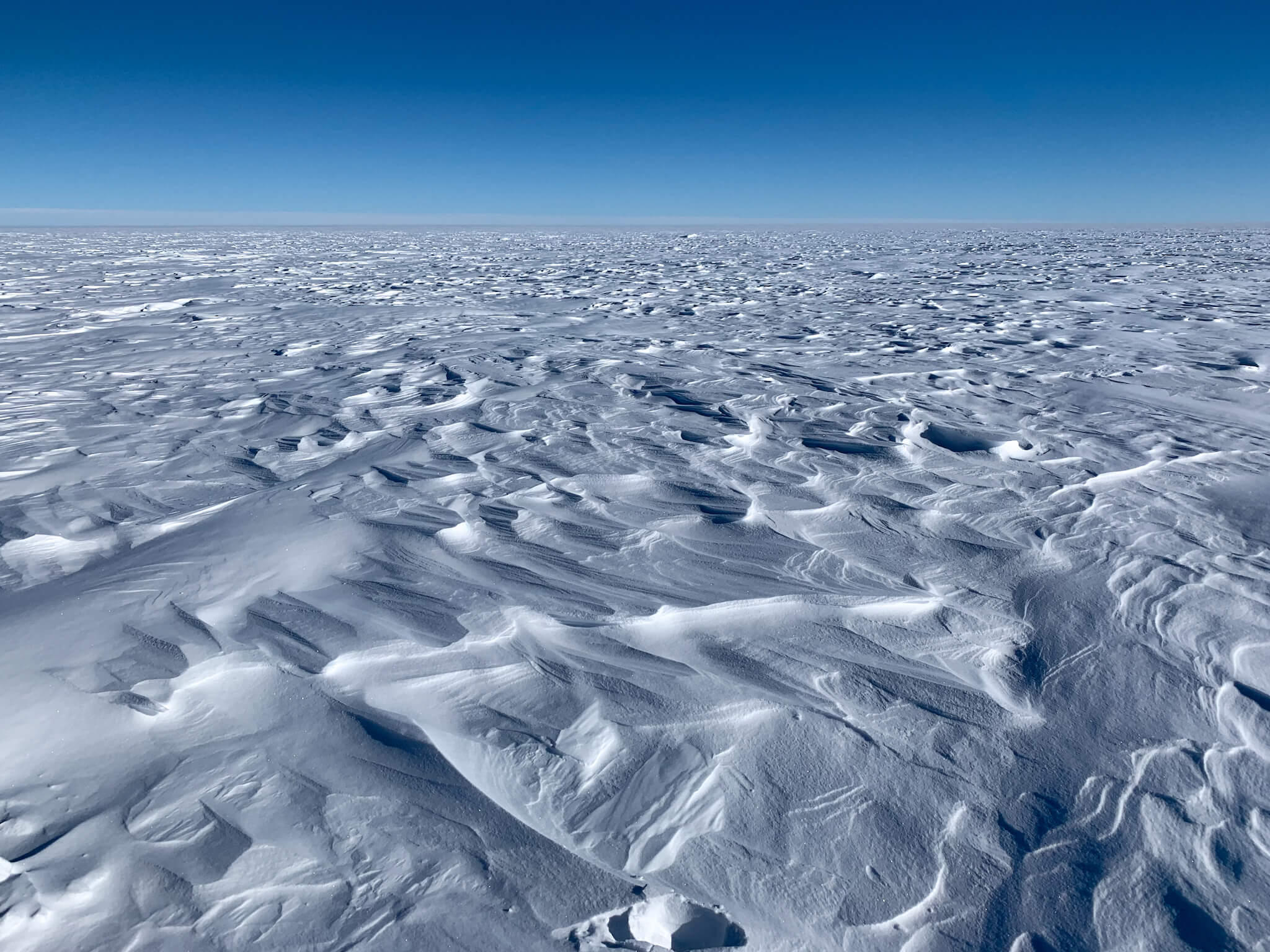

I begin my long walk on November 24, 2018. A small propeller plane dropped me off on the Ronne Ice Shelf, on the edge of the Antarctic continent. I’ve dreamt of it, here I am! Every morning I unzip my tent and find out what my day will be like. Will it be windy, foggy? Or sunshine mixed with bitter cold? Is the surface covered in a fine blanket of snow, or does it give way to imposing sastrugi, large mounds of snow sculpted by the wind? Conditions during the first few weeks of the expedition were Dantean. It’s a hot year in Antarctica. You’d think it would be a godsend for me, but it’s not! The rise in mercury has precipitated a lot of snow on the continent, and my tent finds itself buried under fresh snow. I’m exhausted pulling my sled through 30 or 40 centimetres of snow. Fully loaded, the sled and my skis sink into the powder. I stomp, stumble, fall… But the worst part is finding myself in the whiteout and not knowing where I’m going. This atmospheric optical phenomenon blends snow and sky into a white glow and cancels out all contrast and sense of depth. At times like this, I lose all my bearings. It’s exhausting to walk blind, unable to set a course in the distance. My gaze is lost in a white immensity, my eyes riveted to my compass. I feel like I’m in a ping-pong ball or walking with a white pillowcase over my head. So I concentrate on what I can control: my breathing, the glide of my skis and the management of my thought flow. I try to chase away the bad thoughts and convince myself that this capricious weather will only last for a while, that it’s a bad time to be out. When all the elements are against me, I try to bring my South Pole dream back to the surface. Above all, not to succumb to the temptation to give up.

The days go by and the quality of the snow doesn’t improve. I’m progressing at 1.5 km/h. At this rate, I don’t have enough food to complete the expedition. So to keep going, I decide to set myself a very precise routine. I ski in one-hour blocks. At the end of each session, I stop for 5 minutes to eat and drink. I ski up to 12 hours a day. I’d never have imagined such intense days. But I have to keep moving, my food reserves are dwindling and I have to reach the South Pole before the end of January, by which time the continent will be gradually enveloped in the polar night. This almost military routine helps me put one ski in front of the other. The watch guides me, and I rely on it. It dictates my day, when I take my breaks and when I take off my skis. Without her, and without this slightly irrational attraction to the Pole, I would never have left my tent. An expedition like this takes time. Thinking about arriving on the first day is totally discouraging. It seems insurmountable to think that there are almost 2 months of solitude and effort ahead of you. To cope with this, it’s essential to deconstruct the expedition into achievable mini-objectives: the next break, the next podcast, dinner… I have to take each day as it comes and accept being battered by bad conditions.

As the weeks went by, I began to feel better and better in this vast desert. As if Antarctica was testing me and playing with me. As if it had to be earned and tamed. Then I entered into total communion with this continent. Every day, I’m more efficient at surviving in such a hostile environment, at reading the ice, at pitching my tent in a strong wind… It’s as if Antarctica had accepted me and opened the way to the Pole. After more than 7 weeks of loneliness and effort, I catch sight of small black dots on the horizon. I shouted “I SEE THE POLE” and collapsed onto my sled. Tears of joy and exhaustion freeze on my cheeks. For the first time, I realize what I’m about to accomplish. So much effort, rigor and perseverance to get this far… So I slow down over the last few kilometers, trying to enjoy and soak up as much of the moment as possible. The Amundsen-Scott scientific base is growing by leaps and bounds. I’m almost there… I touch the metal sphere representing the South Pole on January 13 at 12:15pm. After 51 days, I become the first Frenchman and the youngest person in the world to complete such an expedition. As I arrived, I thought of Jean-Louis Étienne, the godfather of my expedition, and his words: “You don’t push your limits, you discover them”. A mixture of joy and pride washes over me, and I feel as if I’m on cloud nine. I’m already feeling a touch of nostalgia, Antarctica has left its mark on me and I’m leaving a part of myself behind. I’ll be back.

Read the book about this adventure: Le Continent blanc, 51 jours seul en Antarctique, published by Robert Laffont. And the whole expedition on the Objectif Pôle Sud website.