SCIENTIFIC EXPEDITION IN GREENLAND

1,500 km kite-ski expedition from Ilulissat to Qaanaaq

In June and July 2024, I led an expedition to Greenland with the glaciologist Dr. Heïdi Sevestre to collect scientific data on snow density and the pollution present on the surface of the ice sheet.

For one month, we moved through a natural environment completely devoid of human influence — a landscape deeply sensitive to climate change, characterized by its exceptional remoteness, dryness, and purity.

Unlike heavy, polluting mechanized scientific expeditions, we chose to travel by kite-ski — a lightweight, zero-emission mode of transport. We set off from Ilulissat on the west coast, bound for the Inuit community of Qaanaaq in the far north of the island — a 1,500 km journey by kite-ski.

Welcome to Ilulissat, a town of nearly 5,000 inhabitants on Greenland’s west coast.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Ilulissat region is home to the Sermeq Kujalleq Glacier, one of the most active glaciers in the world. It is responsible for about 10% of all icebergs produced in Greenland.

We take advantage of the midnight sun to observe the glacier up close before beginning our expedition northward.

Departure! After months of preparation, we are finally on the ice sheet with Heïdi. We make a complementary duo. Heïdi is a glaciologist specializing in glacier dynamics, tropical glaciers, and Antarctic ice shelves. She holds a Ph.D. in glaciology from the University of Oslo and works at AMAP (the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme), where she coordinates research on climate, pollutants, and ecosystem health in the Arctic. Her mission is to improve the visibility of climate knowledge for governments, communities, the public, and businesses, and to implement concrete, effective actions against climate change.

We launch our kites for the first time. They soar into the deep blue sky and gently pull us forward. At this early stage of the expedition, we must absolutely gain altitude — the edge of the ice sheet is riddled with crevasses, meltwater lakes, and rivers.

Our sleds (pulkas) glide smoothly across the all-white landscape. They carry everything we need to live autonomously on the ice sheet: stove, tent, sleeping bag, mat, rope, crevasse rescue gear, rifle (mandatory in case of a polar bear attack), expedition clothing, batteries, solar panels, cameras, satellite communication devices, scientific instruments, repair kits, and a spare pair of skis… Each of us has 30 days of food, 7 liters of fuel, and 4 kites of different sizes. Everything is divided between two pulkas, for a total load of about 120 kg. In the distance, we can still glimpse the mountains and the coast of the ice cap.

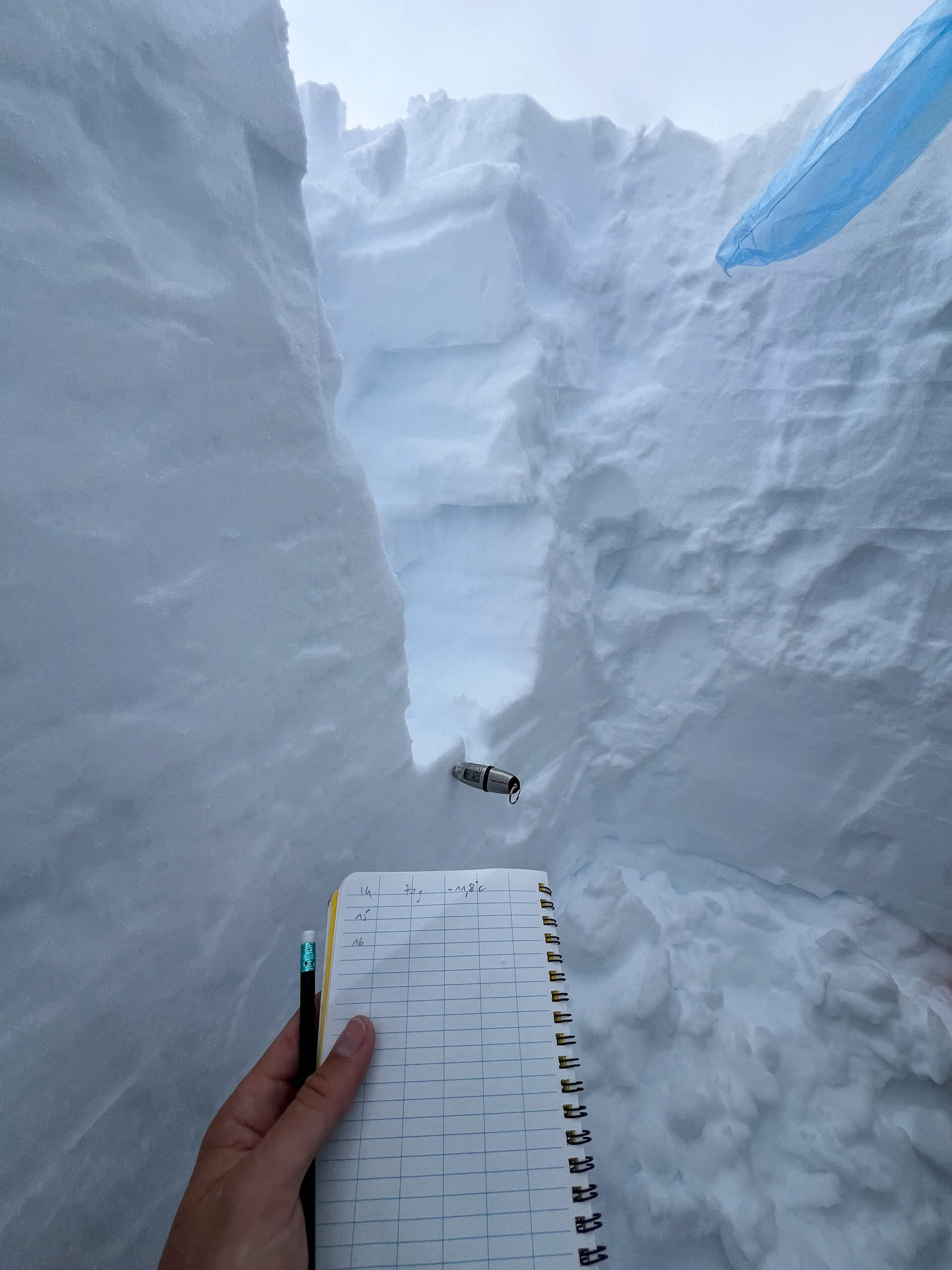

We take advantage of a windless day to begin our polar research program. With Heïdi, we dig a 1.5-meter-deep pitdown to the ice to measure snowpack density.

Next, we take small snow cores at regular intervals to weigh and measure their temperature. These data are essential to validate satellite observations and estimate how much snow Greenland receives each year.

Our camp sits at 2,400 meters above sea level. Beneath our feet lie several kilometers of ice — dizzying! With climate change, Greenland is currently losing 30 million tons of ice every hour (!). If all the ice were to melt, global sea levels would rise by 7 meters.

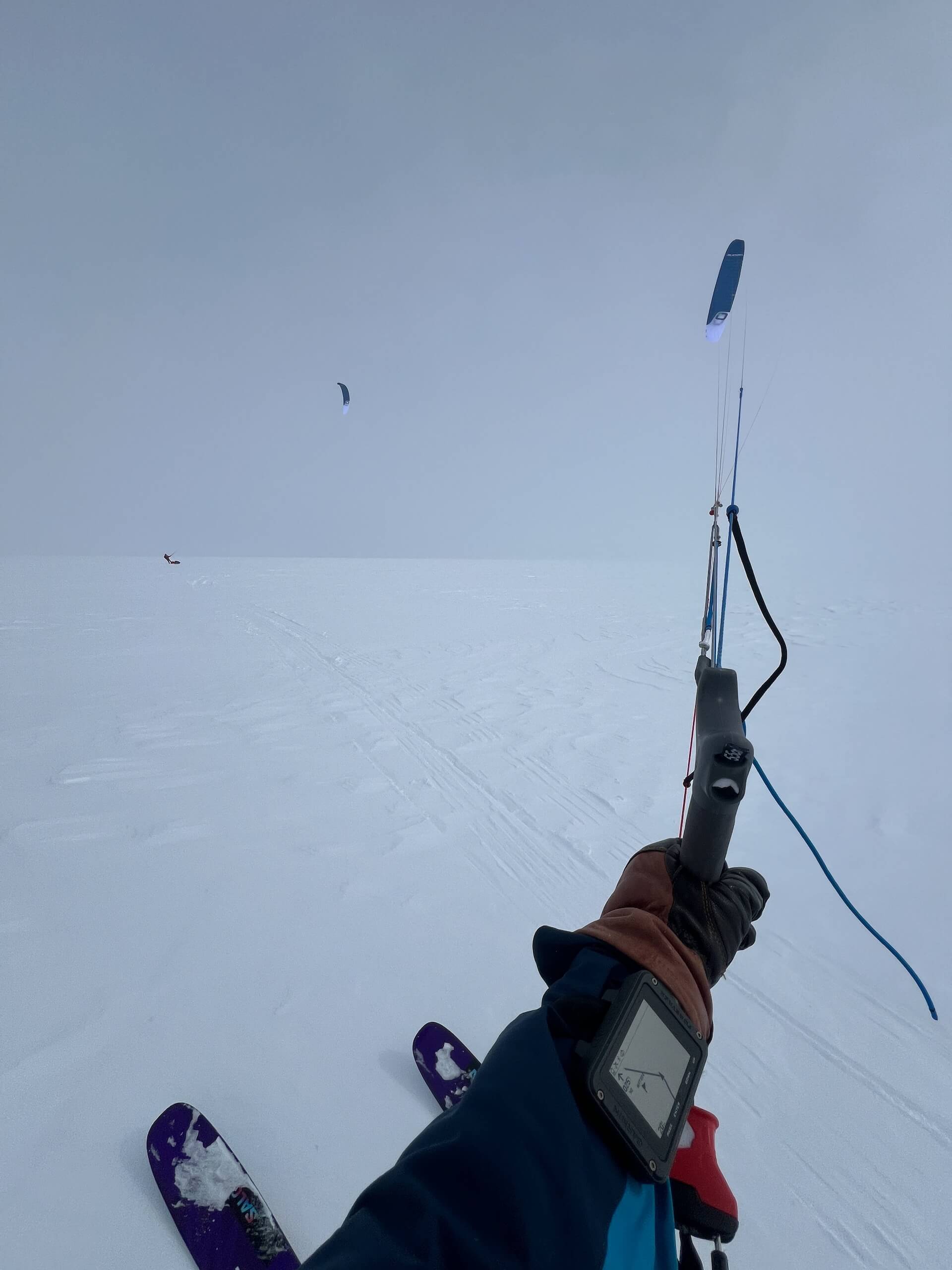

Ideal conditions: perfect wind, surface, and visibility! The southeast wind fills our 15 m² wings, sometimes propelling me to 40 km/h. The fresh but shallow snow glistens like a shimmering carpet beneath us.

Usually, once we’re moving, we stop every two and a half hours to eat and drink. We can kite without worrying about nightfall, as at this time of year the sun never sets. It dips slightly on the horizon, but daylight is permanent.

At midday, we were treated to a spectacular sight: the sun broke through the clouds and an enormous parhelion (sun halo) appeared — multiple giant rings encircling the sun.

This luminous phenomenon is caused by the reflection of sunlight on ice crystals in the sky. It was surreal and breathtaking. In these dreamlike conditions, we covered 217 km in a single day!

With a light tailwind, we make wide sweeping motions with our kites, zigzagging across the pristine surface.

We dig two 1.8-meter-deep snow pits, leaving a thin snow wall between them to observe, in cross-section, the density and composition of the snowpack.

Each layer represents a different weather episode. The bright lines often correspond to melt events. By analyzing snow density and composition, we can look back in time and determine annual snowfall accumulation in Greenland.

Since the beginning of the expedition, I have been collecting snow samples at regular intervals. I melt them and filter them using a syringe filter.

Each filter is carefully preserved and will be delivered, upon my return, to the University of Colorado Boulder (USA). There, they will be analyzed to determine the quantity and origin of black carbon in the snow. Black carbon is a microscopic air pollutant — a residue from fossil fuel and biomass combustion (such as forest fires). When it settles on Greenland’s ice sheet, it darkens the surface and, since dark colors absorb more sunlight, accelerates melting. We say that it affects Greenland’s albedo by reducing its ability to reflect sunlight.

Every morning, the same ritual: analyze the wind strength to choose the right kite, lay it out carefully, and make sure all the lines are untangled…

…and finally, take off!

La tente est aussi bien un refuge contre les éléments qu’un rempart contre l’immensité.

The tent serves both as shelter from the elements and as a barrier against the immensity of the landscape. Inside, a small routine unfolds: set up our sleeping bags, melt ice for water, eat, assess our progress, and rest.

Today we must sail slightly upwind. To do this, we have to edge the skis as much as possible. Our bodies lean to one side to counter the 15 m² wing that constantly tries to pull away from the wind. Bent low, almost sitting, arms outstretched, we pull on the control bars to steer the kite and generate power. But it’s exhausting — our legs burn and beg for relief.

To navigate, we wear a Garmin Foretrex GPS on our wrists, preloaded with waypoints. It’s less romantic than steering by sun and wind, but much more practical when visibility is poor.

Despite our altitude (2,641 m), it feels “hot” — between –5°C and –10°C. Inside the tent, under sunlight, the greenhouse effect can raise the temperature to +15°C!

At each camp, I collect a snow sample for filtering and analysis.

As we approach Qaanaaq, mountains begin to appear. We gradually lose altitude. Near the edge of the ice sheet, we cross crevasses (covered by snow bridges) and numerous meltwater rivers, kites still flying above us.

What a joy to finally glimpse the coast and the surrounding landscape!

Only 750 meters from our goal, the wind dies. We attach skins to our skis and pull our sleds by hand to reach the snow’s edge.

After 1,500 km of kite-skiing from Ilulissat, we reach the edge of the ice sheet — it took us 15 days!Arrivés sur le bord de la calotte polaire après 1 500 km de kite-ski depuis Ilulissat. Il nous aura fallu 15 jours !

But the adventure isn’t over. We still have 8 km and 800 m of descent to the Bowdoin Fjord — a completely wild stretch of land.

We carry about 260 kg of equipment, which we must haul down on our backs — impossible to pull the pulkas here. We divide the load into four trips, each of us carrying 30–35 kg per trip.

The end of our expedition is exhausting. There is no trail to the coast, and we must find our way through rock, soil, and mud.

After immense effort, we finally manage to bring all our gear down to the fjord, where we are scheduled to be picked up by boat and taken to the village of Qaanaaq.

We wait six days for the boat. Here, in the far north of Greenland, it’s the transition season. Just days earlier, Bowdoin Fjord was still choked with ice, and sea ice near Qaanaaq made launching boats impossible. Gradually, the ice retreated, opening the water.

At 77° North, Qaanaaq is Greenland’s northernmost settlement, with around 600 inhabitants.

At this time of year, the sun dips toward the horizon but never sets. In the evening, we admire the magnificent skies and icebergs.

It’s time for us to head back south and say goodbye to Qaanaaq.

On the way, we take one last look at Greenland’s sublime coastline.

The Arctic is warming three times faster than anywhere else on Earth. The future of our planet depends largely on the health of the poles. Today, Greenland loses the equivalent of 30 million tons of ice every hour. If this ice were to melt entirely, it would raise global sea levels by 7 meters.

Science has no impact unless it is communicated. With Heïdi’s scientific expertise, my polar experience, and our shared passion for ice, we strive to make our discoveries accessible to everyone, bringing the polar regions closer to people’s minds and hearts.

This expedition could not have taken place without the support of our partners: Nollet, Egerie, and Garmin — a huge thank you to them.