NORTH-WEST PASSAGE ON SKIS

400 km on the pack ice, from Cambridge Bay to Gjoa Haven

Heading for the legendary Northwest Passage! 400 kilometers of self-sufficient expedition on skis on the pack ice between Cambridge Bay and Gjoa Haven.

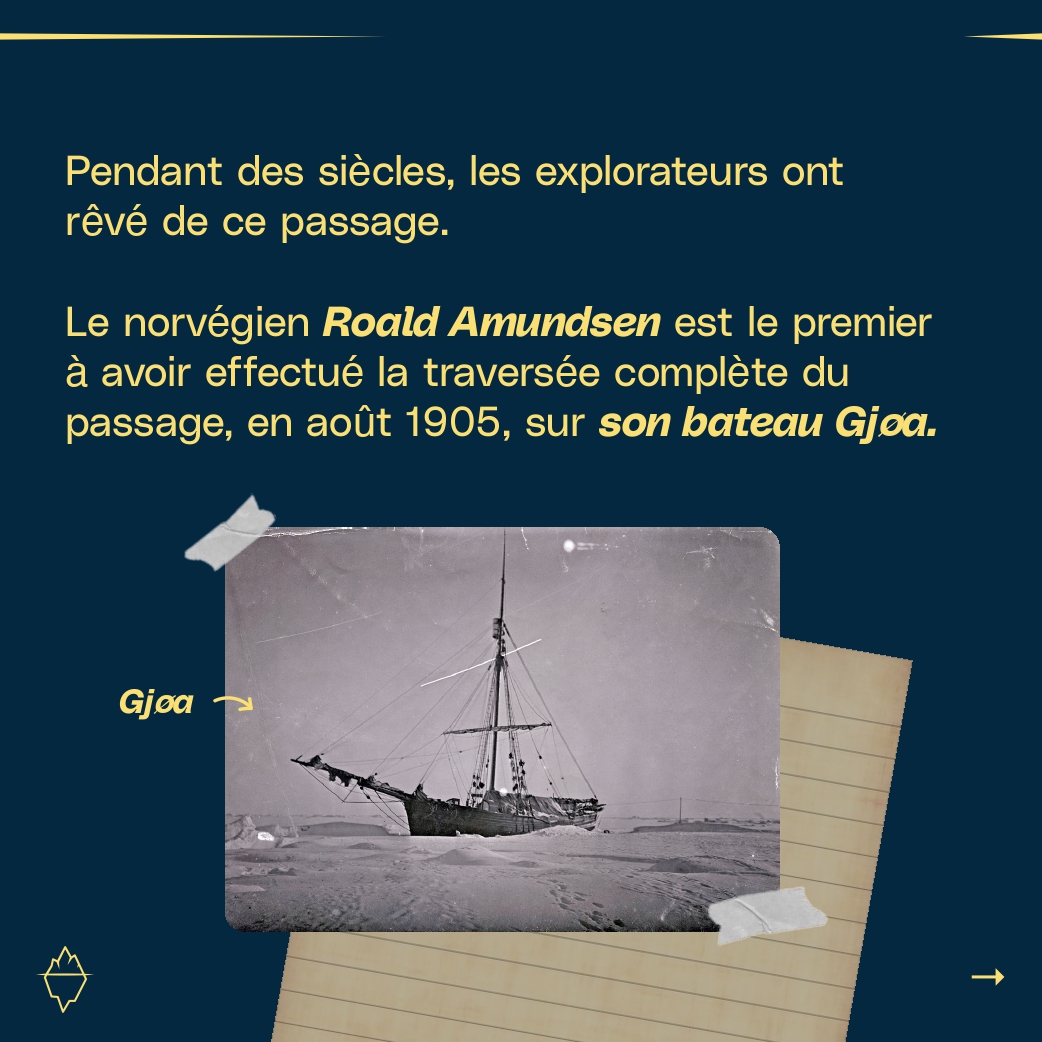

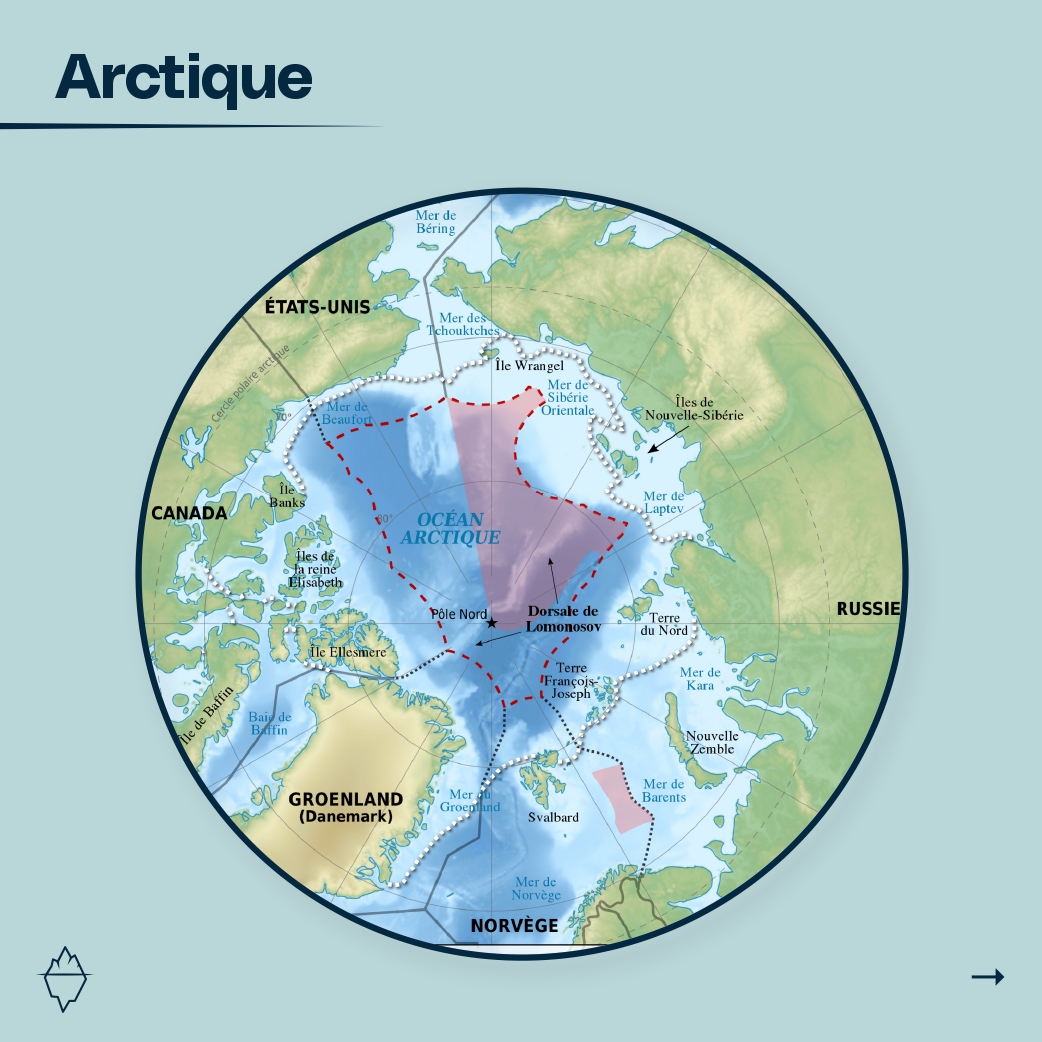

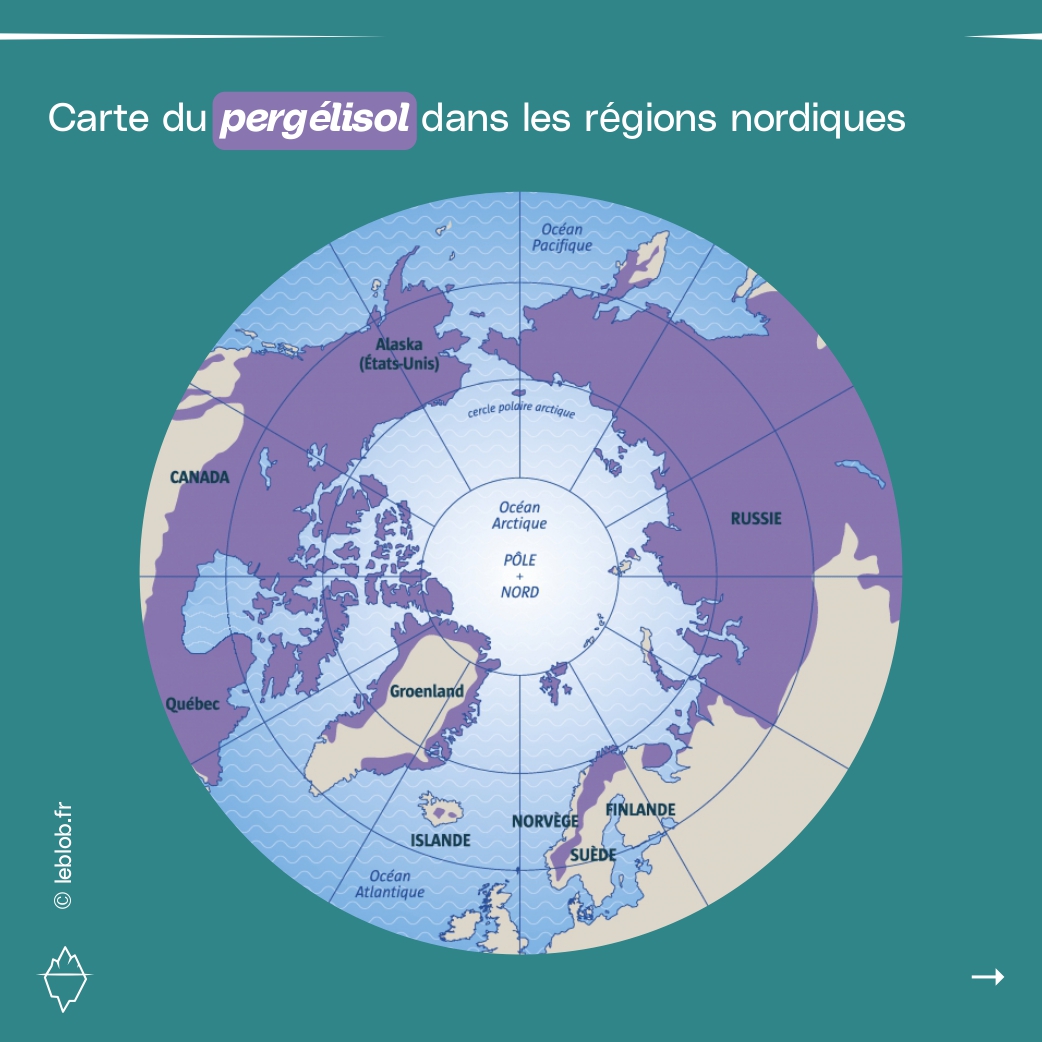

This route is a maritime route in the heart of the Canadian Arctic, linking the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. It was first opened in 1905 by explorer Roald Amundsen. In winter, the passage is frozen over and populated by polar bears and a few Inuit communities.

For this expedition, I’m teaming up with Anja Blacha, an exceptional German adventurer and mountaineer. We’ve been wanting to join forces for a polar expedition for years. So it’s decided: in April 2023, we’ll meet up in Canada’s far north.

Arrival at Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. At 69° North, we’re in the heart of the Arctic.

It’s a small Inuit village of 1,800 inhabitants on the Northwest Passage. In April, the average temperature is -21°C.

After a short day of preparation, we left Cambridge Bay at around 5pm on April 7th, in bright sunshine and -25°C temperatures. We now have 400 kilometers to cover on the pack ice, and we’re off!

As we left the village, a woman who had been skiing met us. Attracted by our easterly heading and our loaded pulkas, she assails us with questions. We tell her we’re off to Gjoa Haven on skis. She can’t believe it, but thinks it’s a great idea!

We’re soon immersed in the great white. A gentle breeze covers the warmth of the sun’s rays. The few particles of ice in the sky create a solar halo.

The start of a polar expedition is always a shock to the body. You leave your warm comfort behind and find yourself in a freezer where you can’t do anything with your bare hands.

We’re slowly getting used to our little expedition routines: skiing, taking regular breaks and eating with huge mittens, wrapped up in our down jackets. The cold is biting!

Our first polar bear track! It’s impressive to imagine the size of this animal: the length of its imprint is twice the size of my hand from wrist to index finger. For us, the bear is a threat. We are equipped with an attack-prevention device (pepper spray, smoke, horn…) and, as is customary (and as a very last resort) a shotgun. At night, we sleep with a headlamp around our necks, so we can get out as quickly as possible if he comes to visit us…

The days on the pack ice are long. We ski around 11 hours a day, covering around 30 kilometers depending on the conditions. When evening comes, we quickly unhook ourselves from our pulkas and take off our skis to set up the tent. We put up everything we need for the night: food, stove, sleeping bag, sleeping mat, clothes… Setting up the tent takes just a few minutes.

Melting snow and ice, on the other hand, takes much longer. We need to make 6L of water every 24 hours, which easily takes 2h with a stove. So we take it in turns to refill the pan while wolfing down our freeze-dried dinners.

The surface of the Arctic Ocean is sublime. Beneath our feet, thick pack ice formed at the start of winter. Beneath this pack ice lies the ocean, hundreds of metres deep.

As you approach Jenny Lind Island, the Northwest Passage bristles with compression ridges and ice blocks of all sizes. Anja Blacha

In the crevices of the ice, we pull our 85kg pulkas like mad.

This is what the Arctic Ocean really looks like: a chaos of frozen blocks of ice. As the ice floes form in winter, wind and ocean currents knock them apart. The result is a battlefield spectacle.

On this section, we advance at a snail’s pace. In the tricky passages, we have to take off our skis, pull the pulkas by hand and avoid falling between the rock-hard blocks of ice. It’s an exhausting process that slows us down considerably. Anja Blacha

Between the compression ridge fields, there are sometimes flatter areas. We make use of these, even if it means changing direction completely and heading north. This is the best way to get around the huge blocks of ice blocking our path.

The spectacle of the Arctic ice pack.

Exhausted, after a ten-hour effort, we pitch our tent in the middle of an ice chaos, hoping that conditions will improve for the rest of the trip. In the evening, we take stock. What matters to us is the distance covered as the crow flies (in a straight line) since the last camp. As we zigzag our way through this obstacle-ridden terrain, we sometimes make more than 5 kilometers of detours in a single day.

The alarm goes off at 6:20 in the morning. The fatigue of the previous days can be seen on our faces. The first step of our day is to get out of our icy sarcophagus. Humidity in an Arctic tent is enemy n°1. We sleep in waterproof bags (called VBL: “Vapour Barrier Liner”) to prevent our perspiration from transferring to the feather sleeping bag. While sleeping, a human loses up to 200 cL of water through respiration and perspiration. If this moisture migrates to the sleeping bag, it will freeze and become unusable. On top of this, we add a large over-bag to protect the sleeping bag from any frost that might come off the tent walls. Getting out of these 3 bags is quite a task!

Every 70 minutes, we take a 5-minute break sitting on our sleds. For lunch, we take off our skis and stop a little longer. These stops also mark a change in the person leading the way. This allows the person behind to take over the navigation.

The surface doesn’t make our work any easier. It’s as if it had been turned over by a giant tiller. We need to read it as well as possible.

We regularly climb over blocks of ice to try and find the best passage in the distance. Anja Blacha

It’s a constant slalom between boulders, where it’s crucial to anticipate trajectories as much as possible.

Left? To the right? Our horizon looks like this. Fortunately, the weather is on our side. I can’t imagine sailing in a whiteout on this terrain… Temperatures are mild (-15°C) and the sun is with us until 8:30pm. The low-angled light on the pack ice is magnificent and almost makes us forget that we’ve spent 12 hours battling with it.

It looks like the compression ridge field is behind us. At the break, I retrace my steps, hoping not to go back there any time soon – we’ve lost a lot of strength there.

Once again, we come across the tracks of a polar bear. Its footprints are clearly visible on the pack ice, but the hard, solid surface tells us they’re not so recent.

The joy of a clear horizon and the pleasure of sailing on flat pack ice. We take advantage of these favorable conditions to make good progress, recording days of over 35 kilometers.

Cool temperatures have returned, with a slight -20°C in the early evening. The heat generated by the effort crystallizes instantly.

To be as quick and efficient as possible after the day’s skiing, I start the stove to melt snow before I even pitch the tent. Anja Blacha

Arriving on King William Island, we were greeted by a large radio antenna. It’s an American surveillance system called “Dew Line”, which surrounds the entire Canadian Arctic. We’ve left the pack ice and are now on dry land. We’ve only got 100 kilometers to go to the finish.

Now that we’re back on dry land and away from the pack ice, we’re regularly spotting muskox tracks.

Our route undulates over the hills of King William Island. In the distance, a herd of muskoxen appears on the horizon. We try to approach them, but they’re fearful, hunted by the Inuit. Anja Blacha

We pitch our tent next to around fifteen individuals of this emblematic Arctic species. It’s relatively warm (-11°C) and the snow has softened. Through the snow, we can sometimes make out mosses and lichens that are just waiting for spring to arrive.

Breakfast 40 kilometers from Gjoa Haven © Anja Blacha

One ski in front of the other, each stride brings us a little closer to our goal. It’s mechanical, repetitive, sometimes monotonous, but there’s great satisfaction in the slow effort and autonomous progress in this hostile universe. Anja Blacha

The last few strokes of the skis are fast and we’re going at full speed, as if magnetized by the houses. We know that this evening, we’ll taste the joys of civilization again: a shower and a sit-down dinner.

After 14 days of expedition and 400 kilometers of self-supported expedition on the pack ice, we reach our goal and the hamlet of Gjoa Haven. We’ve done it!

It’s been a wonderful expedition. Teaming up with Anja was fabulous. Our shared polar experience enabled us to move fast and perform well on the ice. It’s a world that’s always difficult to get to grips with, and together we brought a lot to each other.

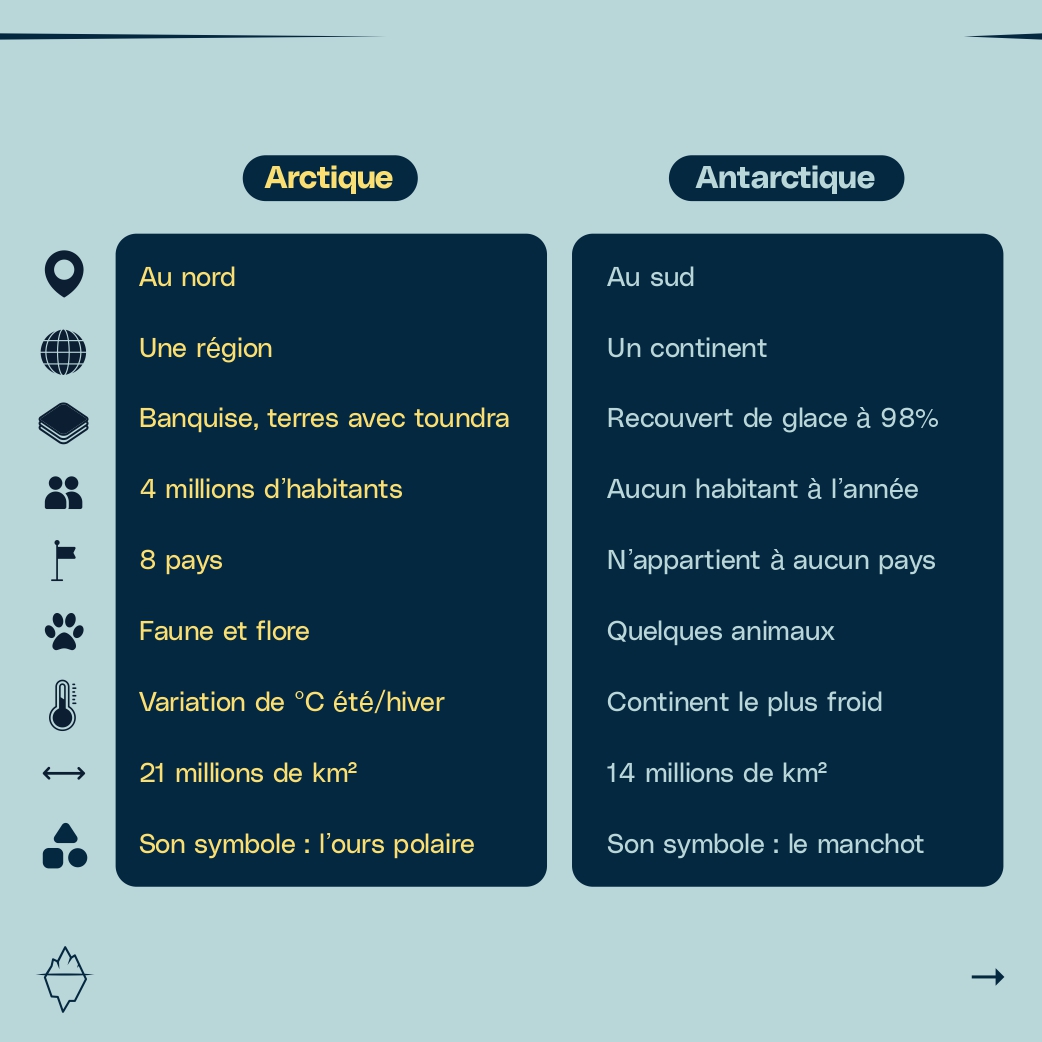

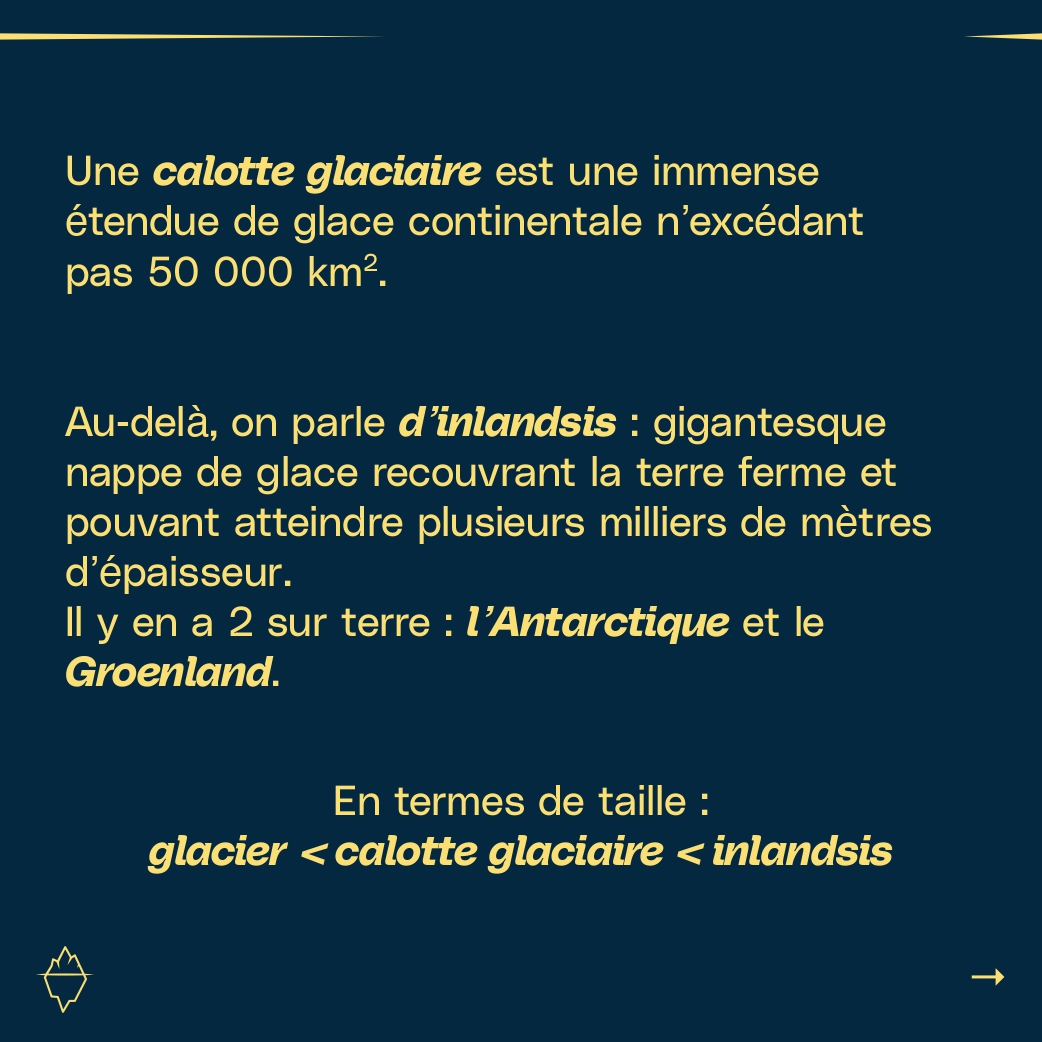

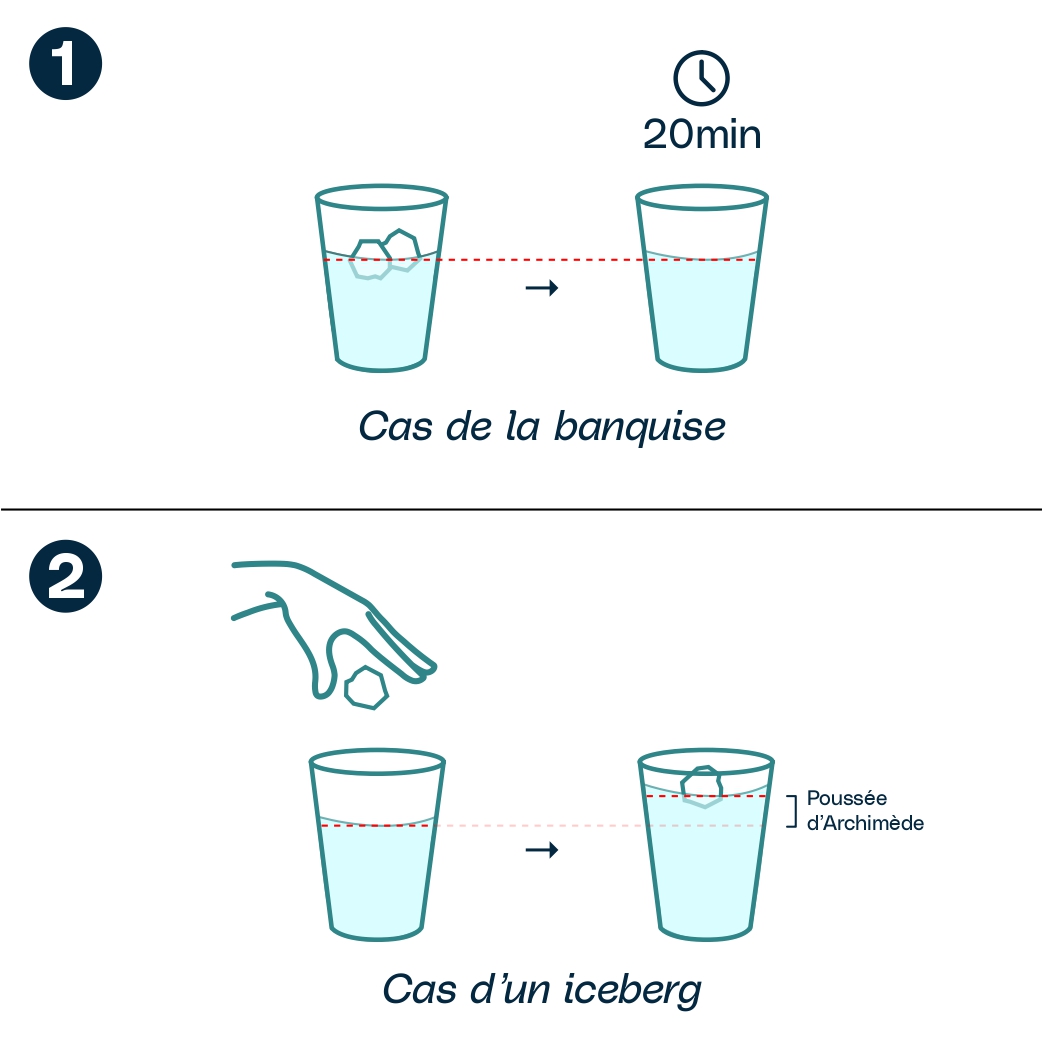

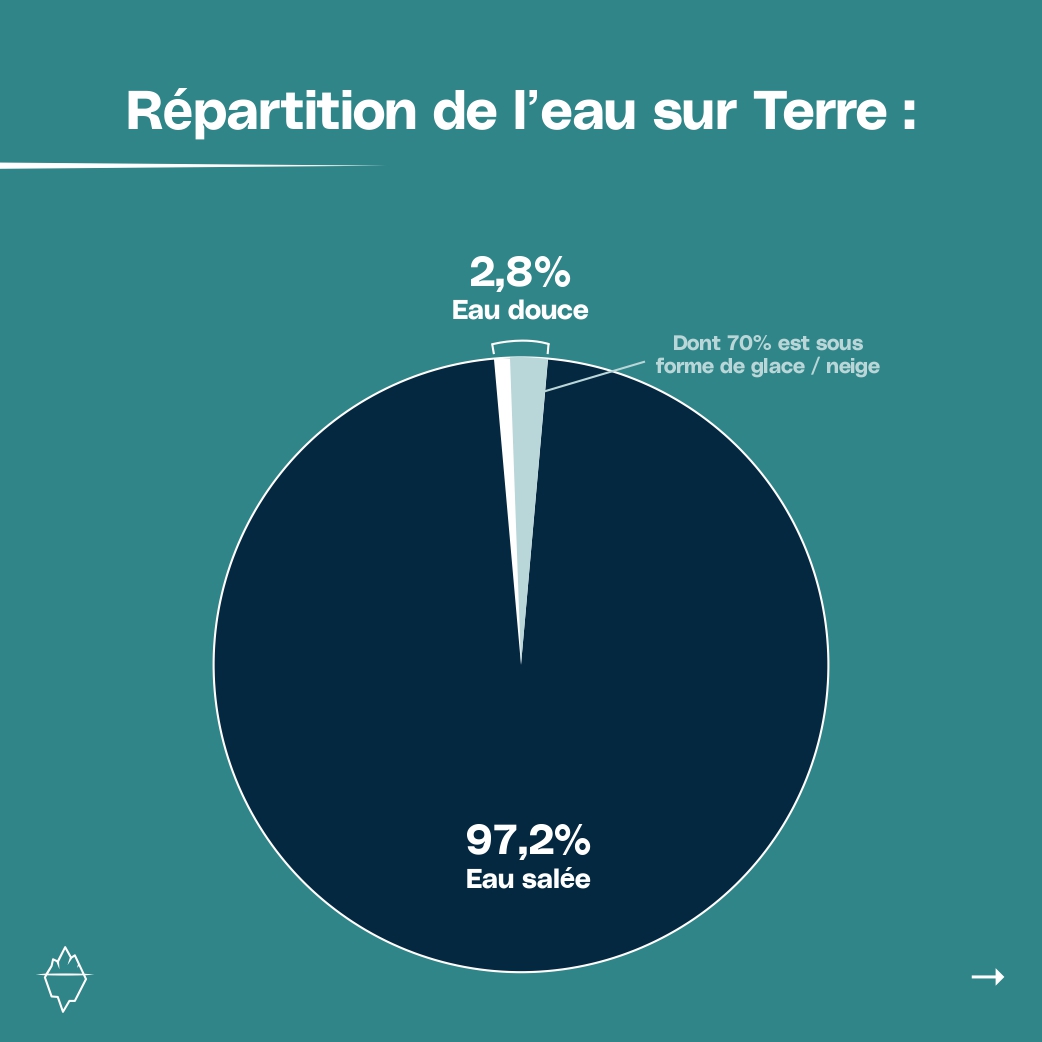

The Northwest Passage is pretty wild. In winter, it’s still frozen solid. But for how much longer? Today, the polar worlds are on the front line of global warming, yet they are of vital importance to our planet’s climatic equilibrium – as explained in the 6 infographics shared during the expedition ( Twomorrow production).

This adventure would not have been possible without the support of my partners: Nollet Électricité, Niort Frères and Egerie.