MARATHON DES SABLES

250 km ultra-trail in the Sahara

I’m not much of a runner; I don’t even know if I like running. What I do love, however, is adventure, being on my own in a hostile environment. It was for these reasons that I decided to sign up for the Marathon des Sables, a 250 km long, self-supporting, stage race in the Sahara desert. The Marathon des Sables has the reputation of being one of the toughest races in the world. It’s true that the race is intense, especially for those who do it in the lead. But the time barrier at the checkpoints is high, so the probability of finishing the race is quite high. But that doesn’t take anything away from the difficulty of the terrain and the heat. During the race, I had to deal with dunes, stony plateaus, dry wadis and small mountains, all in 6 stages ranging from 30.3 to 86.2 km, sometimes in temperatures of 51°C. I took part in the 32nd Marathon des Sables in April 2017, so before setting off I knew it was going to be tough. It was.

The Paris-Normandie daily of March 10, 2017. In addition to my weekly outings in Paris, I did a full-scale training run of 85 km along the Normandy coast, from Dieppe to Étretat.

For a race like the Marathon des Sables, the weight of the bag is of prime importance. With the exception of compulsory equipment, each runner is free to take what he or she wishes. It’s all a question of compromise between bag weight and comfort. A light bag will shorten the race time, while comfort on the bivouac will help you recover better. According to the regulations, the rucksack must weigh between 6.5 and 15 kg (excluding water) and include the following compulsory equipment. A race bag, a whistle (integrated into the bag), a sleeping bag, a headlamp, a compass, a signal mirror, a knife, a lighter, a survival blanket, an aspivenin pump, sun cream (not on the photo), 200€ in cash (not on the photo), a passport. In addition to the compulsory equipment, here’s what I took with me: a ground sheet, a light bivouac windproof suit, running shorts with bib shorts, compression sleeves (not on photo), a long-sleeved running tee-shirt, a tee-shirt and technical tights for the bivouac, a pair of flip-flops, cleaning wipes, trail sneakers, gaiters, two pairs of trail socks, a buff, a Saharan cap, a GPS watch, walking sticks, sunglasses, an iPod Shuffle, headphones, an iPhone and iPhone cable (not in photo), an external battery, a toothbrush and toothpaste, a bowl (not in photo), a spoon, a stove, tablets for the stove, two cans of water, a roll of toilet paper. As the race was self-sufficient, my bag also contained meals and food for 6 days. All my meals were freeze-dried and repackaged in freezer bags, for a total weight of around 4.5 kg and an energy value of 20,000 calories. Stéphanie Itsuko

Official photo after bag check. At the weigh-in, I have just 10 kg on my back, to which I’ll need to add 3L of water.

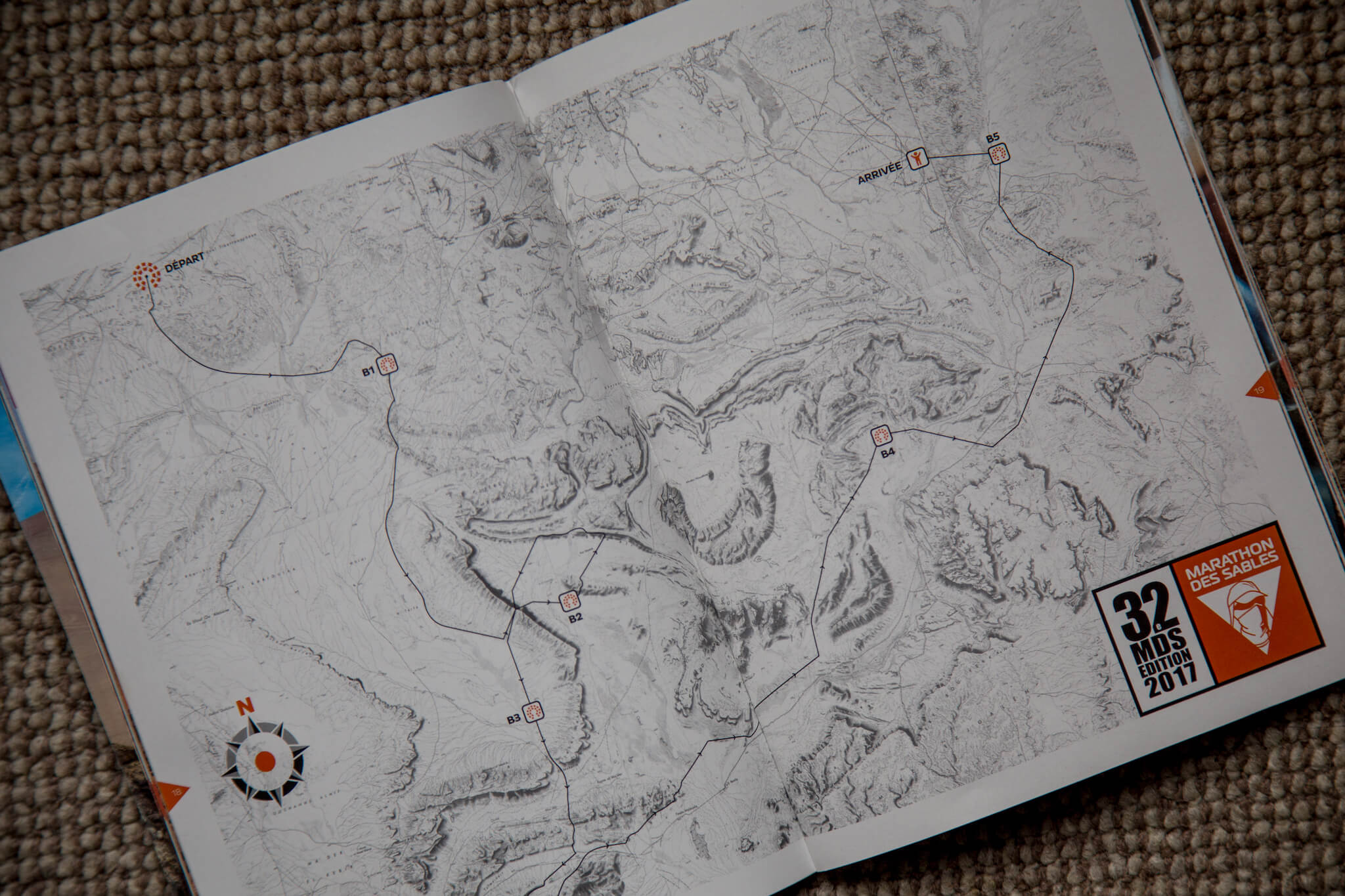

The route of the 2017 edition of the Marathon des Sables is 237 km long. The first stage: 30.3 km, the second: 39 km, the third 31.6 km, the fourth: 86.2 km, the fifth: 42.2 km and the last, the solidarity stage: 7.7 km. Although the route is fairly “short” this year, it is characterized by a significant altitude difference, with the ascent of several jebels (rocky mountains).

The Marathon des Sables is a race that was created in 1986. The 2017 edition brings together just under 1,200 runners, 20% of whom are women. The first day of the event is an administrative day, with bag and electrocardiogram checks, salt tablets to be ingested during the race, and so on.

To support the heavy logistics, 450 volunteers and employees work on the race. In the early evening, some of them take advantage of downtime to relax.

The bivouac has 300 Berber tents, which are set up and taken down daily. There are 8 of us per tent, and we keep the same team throughout the race. Thanks to my friend Thomas, a former volunteer podiatrist, I find myself surrounded by his friends, all former controllers and nurses on previous editions. The atmosphere is festive, and I couldn’t have come at a better time.

Moroccan logisticians build fires in the evening. On the eve of departure, some of us gather here, both impatient and curious to find out what the next few days have in store for us.

On Sunday April 9, we set off into the dunes of southern Morocco to the sound of AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell”. These first moments are liberating. They put an end to long months of physical and logistical preparation. I’m relieved to be finally taking my first steps into the desert and tackling this sporting challenge.

The dunes give way to large stony stretches. As they are flat, they allow you to move forward more quickly, but when they are several kilometers long, they are hard on the morale.

I’m more comfortable in the dunes. The contact with the sand is more pleasant than the pebbles, which takes the pressure off the soles of my feet. Progress is slower than on the plains, but I can rely on my poles, which make walking much easier.

There are checkpoints every 10 km or so along the route. At each stop, you receive 1.5 or 3 liters of water, or 1 or 2 bottles.

It’s also an opportunity to rest for a few minutes in the shade before continuing the race.

Each running at his own pace, we meet up in the evening as we arrive in tent n°59. We use our free time to treat our feet at the clinic, rest and eat.

Each arrival at the bivouac is a moment of relief, after long hours spent under the scorching desert sun.

We wake up at 6am to give ourselves time to get ready before setting off on a new stage at 8:30am. For breakfast, I eat freeze-dried tabbouleh which I re-hydrate with cold water. Thanks to sports journalist Peggy Bergère for following me throughout the race for the sports daily L’ÉQUIPE (find my interview at the bottom of the page) © Jean-Marie Gueye

I come across wild dromedaries along the way. In the hot season, they can go without drinking for 2 to 3 weeks. As for us, we drink around 12 liters of water a day.

I spend a good part of the race alongside Guillaume and Mathieu, two of my tent-mates. We support each other in our efforts, and that’s good.

There’s no question of stopping for lunch on the run. During the day, I eat salted peanuts, cashew nuts, sausage, fruit pastes and dried apricots.

The route includes several jebel climbs, the highest of which, Jebel El Otfal, rises to an altitude of 800 metres.

These climbs slow our progress, but the views of the desert from the peaks are unforgettable.

On the other side, the descent is perilous and you have to hold on to a rope. In the distance (top right in the photo), you can see the bivouac that marks the end of the stage. It’s 5 km away.

In the soft sand, you can descend at high speed, which frees up your legs after a demanding climb.

Gaiters are virtually indispensable on the race course. Very few runners do without them. Attached to the sneakers, they prevent much of the sand from entering the shoe.

Probably one of the best moments of the day. Seeing the bivouac and the finish line of the stage is always a liberating moment that makes you forget all the troubles of the day.

Finish of stage 3. At this stage of the race, we’ve covered around a hundred kilometers. A webcam is set up near the arch, allowing our loved ones to watch us cross the finish line live after each stage.

An e-mail system has also been set up by the organization. Every evening, we receive the messages addressed to us, which is a real morale booster.

Tabbouleh for breakfast. Food is important on this kind of race. You have to pack enough calories without weighing too much. In the evening, I swallow a dehydrated soup before eating a freeze-dried dish (macaroni and cheese, chicken rice, spaghetti bolognaise…) and a freeze-dried dessert (applesauce).

Every morning in tent 59, we repeat the same gestures. Protecting our feet and toes with elastoplast, dressing, filling our water cans and packing our bags. As the days go by, the bags become lighter and easier to close and handle.

Luke Robertson is a Scottish professional adventurer (www.lukerobertson.org). I met him on my expedition to Greenland (see “Greenland” adventure), during which we shared the same tent. Following this expedition, Luke skied solo from the Antarctic coast to the South Pole in 39 days (“Due South” expedition). This year, he ran the Marathon des Sables alongside his wife Hazel, with whom he will attempt in summer 2017 to cross Alaska to the Arctic Ocean by bike, foot and kayak (“Due North Alaska” expedition www.duenorthalaska.com). It’s a coincidence that Luke and I signed up for the Marathon des Sables this year, we often bump into each other on the race like here at a checkpoint.

First kilometers of the fourth stage, 86.2 km long. It’s the one I’m most dreading, but we have a maximum of 35 hours to complete it.

The elite runners who set off 3 hours after us that day quickly catch up. It’s impressive to see these athletes in action as they pass us by. Here, British rider Thomas Evans, who finished third overall.

During these long hours of running, I lose myself in my own thoughts. I recall fond memories and think of the future, dreaming of new adventures. Music also helps me to escape and better cope with the continuous effort.

Faced with this hostile environment and our own physical and mental limits, the bonds between each competitor are naturally strengthened. The Marathon des Sables is above all a story of solidarity and sharing.

The heat is overwhelming and there’s no shade. The hours of running between 1pm and 3pm are very hard. At its hottest, it was 51°C.

It’s a privilege to tread the majestic dunes of the Sahara and to cross a small part of this desert.

In the distance, a checkpoint where the race controllers will hand out 3 liters of water.

Night falls on the long stage of day four. By now, Guillaume and Mathieu and I have covered some 50km.

Nightfall at checkpoint 4, where we stop longer to eat a freeze-dried meal. I continue with my two companions to checkpoint 5 (km 56.1) before letting them go ahead. I’m a bit exhausted physically, my feet are aching, I’ve got numerous blisters and I’m sleepy. With 30 km to go, I decide to sleep for 1 hour and set off again just before midnight.

It’s been a difficult and lonely night. I made slow progress, stopping at each checkpoint to rest. Here at checkpoint 7, the last before the finish line, I’m tackling the last 10 km at daybreak.

In the distance, the bivouac.

Faced with this deliverance, I can’t hold back a few tears of exhaustion. I’ve covered 184 km in 4 days.

24 hours after the start, I cross the finish line. I’m still standing, but my poles are a great help.

We spend most of the day resting, exhausted by this demanding stage.

At the end of the afternoon, I have my blisters treated. A team of volunteer doctors and chiropodists take care of us every day, so that we can leave the next day in the best possible condition.

A few minutes before the time barrier, many of us gather at the finish line to welcome the last competitor, 35 hours after the start.

Two Berbers with their camels close the way. They cover the entire course at the pace of the last competitor, making sure that the time barriers at each checkpoint are respected. Being overtaken by the dromedary means disqualification from the race.

At the finish of the fourth stage after 86.2 km in the desert, sweet tea is served to the last finishers.

The fifth and final stage begins. We’re tired, our feet are bruised, but at this stage of the race, there’s no stopping us.

I’m feeling pretty fit on this last day. I accelerate and overtake several groups, then race alone. I’m thinking about the finish line, concentrating on the checkpoints and trying, despite the effort and my aching feet, to enjoy these last moments in the desert.

I’m about ten kilometers from the finish. My feet are swollen and blistered and I’m suffering on the stony track leading to checkpoint 3.

777 metres from the finish. For a few kilometers now, from the moment I see the bivouac, my legs have been racing and I’ve been running at top speed. The euphoria of the finish makes all my pain disappear.

I crossed the finish line with emotion, happy, after 237 km on foot in the Sahara desert.

Despite assiduous tanning of my feet in the months leading up to the race, I couldn’t avoid blisters and overheating. But by treating them immediately, none prevented me from continuing the race or slowed me down considerably.

Finisher’s medal for the 32nd Marathon des Sables awarded by Patrick Bauer himself, the race’s creator.

The last stage of the race is a short solidarity stage. Through its association “Solidarité Marathon des Sables”, the Marathon des Sables builds sports centers to benefit disadvantaged populations in Morocco. We’re doing this last leg with the whole tent 59 team (from left to right: David, Mathieu, Guillaume, Pauline, Greta, Meheza, Thomas and me.

For me, the Marathon des Sables was a dream. At the outset, it was a race that seemed inaccessible to me, too hard, too intense. But after running several marathons in recent years (notably the Pyongyang marathon in North Korea) and an ultra-marathon (the SaintéLyon), the Moroccan race seemed less difficult. I registered many months in advance and to prepare, I ran regularly without overdoing it (between 20 and 30 km per week). What appealed to me most of all was the prospect of finding myself in the middle of the desert, self-sufficient in food, alongside a thousand strangers, with the daily challenge of covering each stage on foot. Sporting performance was of little importance to me, and I took part in the Marathon des Sables to experience an adventure rich in emotion, discovery and adventure. You can find my interviews on the Marathon des Sables website before the event and on the L’ÉQUIPE website during the event.