GREENLAND EXPEDITION

Polar expedition on the Eastern coast

In April 2015, I went to Kulusuk on the east coast of Greenland for a polar expedition and to receive training in survival techniques and evolution in extreme environments. For two weeks, I skied a total of 150 kilometers on the Greenland ice pack with Christian, a Swedish guide, and four other boys from Scotland, England, South Africa and Israel. An exhilarating, wild and rewarding experience.

Head for Kulusuk, a village on Greenland’s east coast in the municipality of Sermersooq.

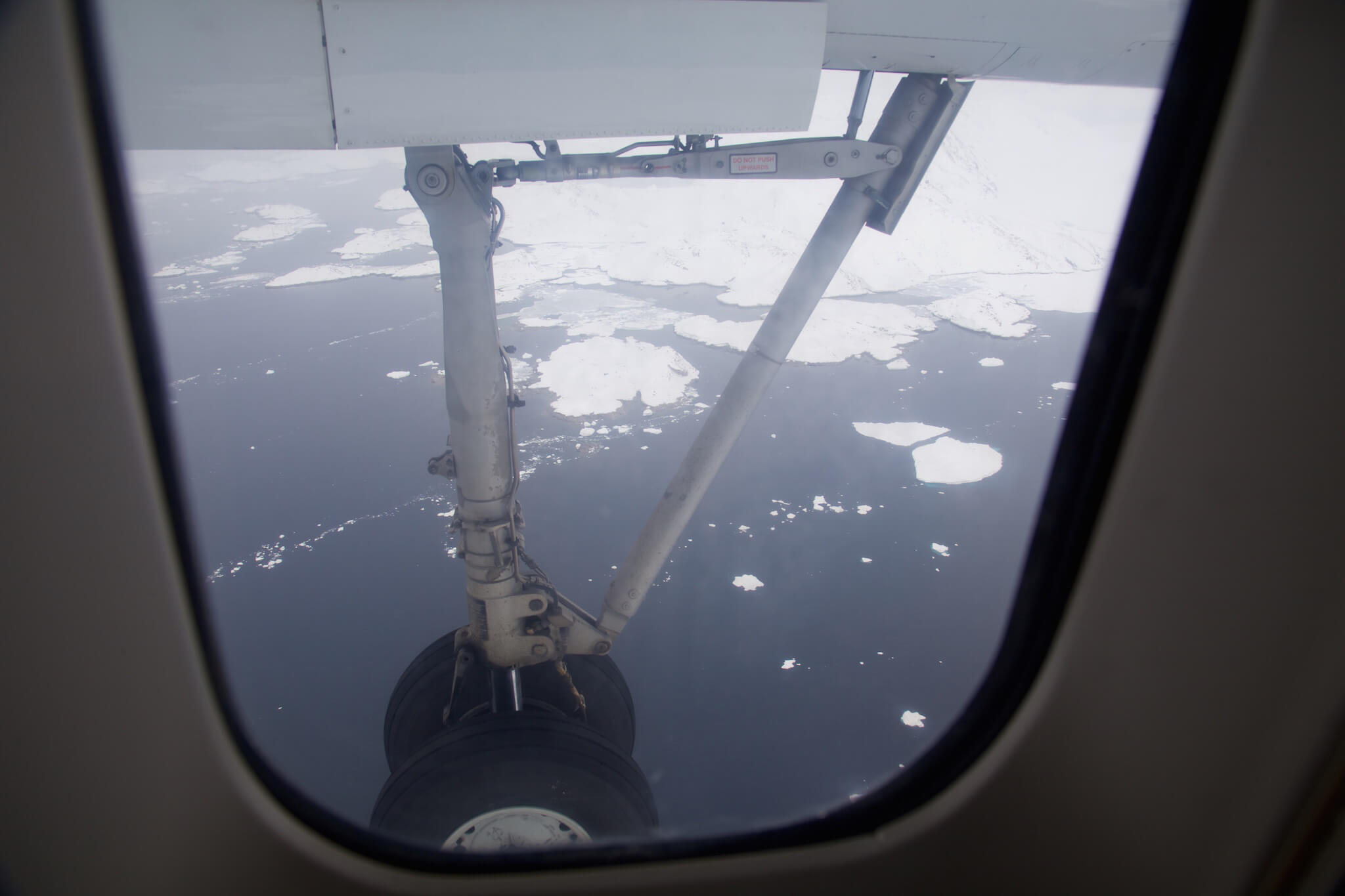

From my porthole, I can see pack ice and drift ice – a sight I’ve been looking forward to for a long time.

The airport is a little way from the village. We reach the village on foot in half an hour.

Although largely subsidized by the state, the Inuit still live from fishing and hunting. Fish is stored outside the house, in the freezer.

After butchering a freshly hunted seal before our very eyes, an Inuit feasts on its still-warm flesh.

Seals are generally hunted on the ice from a motorboat or kayak. In the past, the Inuit used the “hakapik”, a pole with a metal point attached to the end. Today, they use rifles.

Traditionally practiced for thousands of years, mainly for human consumption, seal hunting yields not only fur, but also meat, fat and bones.

Nothing is thrown away. The best cuts are eaten by families, while the offal is used for sled dogs.

According to Christiansen, creator of the Greenland flag, the upper white part of the flag represents the glaciers, which cover 80% of the island. The lower red part represents the sea. The red semicircle represents the sun, while the white semicircle represents the icebergs drifting off the coast. The flag also recalls the setting sun reflected in the sea.

At the last census in 2010, the population of Kulusuk was 286.

Snowfall and strong winds force us to postpone our departure by a day to start our expedition in more favorable conditions.

Greenlandic houses are characterized by their bright colors. Although they are relatively comfortable inside, few families have running water. Drinking water is drawn from a lake where a water pump is installed.

The Kulusuk school, rebuilt in 2005, accommodates 70 children.

On weekends, dog sled races are organized on the pack ice. Five teams of ten dogs start a race of several laps around Kulusuk, with the finish line at the village entrance.

Greenland Dogs are distinguished by their strength and speed. But because of their pack instinct, they need a firm, determined master to be a good pet or working dog.

A Greenland dog a few weeks old.

In April, as spring approaches, the ocean begins to reclaim its rights and break up the winter ice pack.

In a house before the start of the expedition, we take inventory of our equipment and divide up the food we’ll be taking on the ice.

Each of us will ski pulling a pulka weighing around 60 kilos.

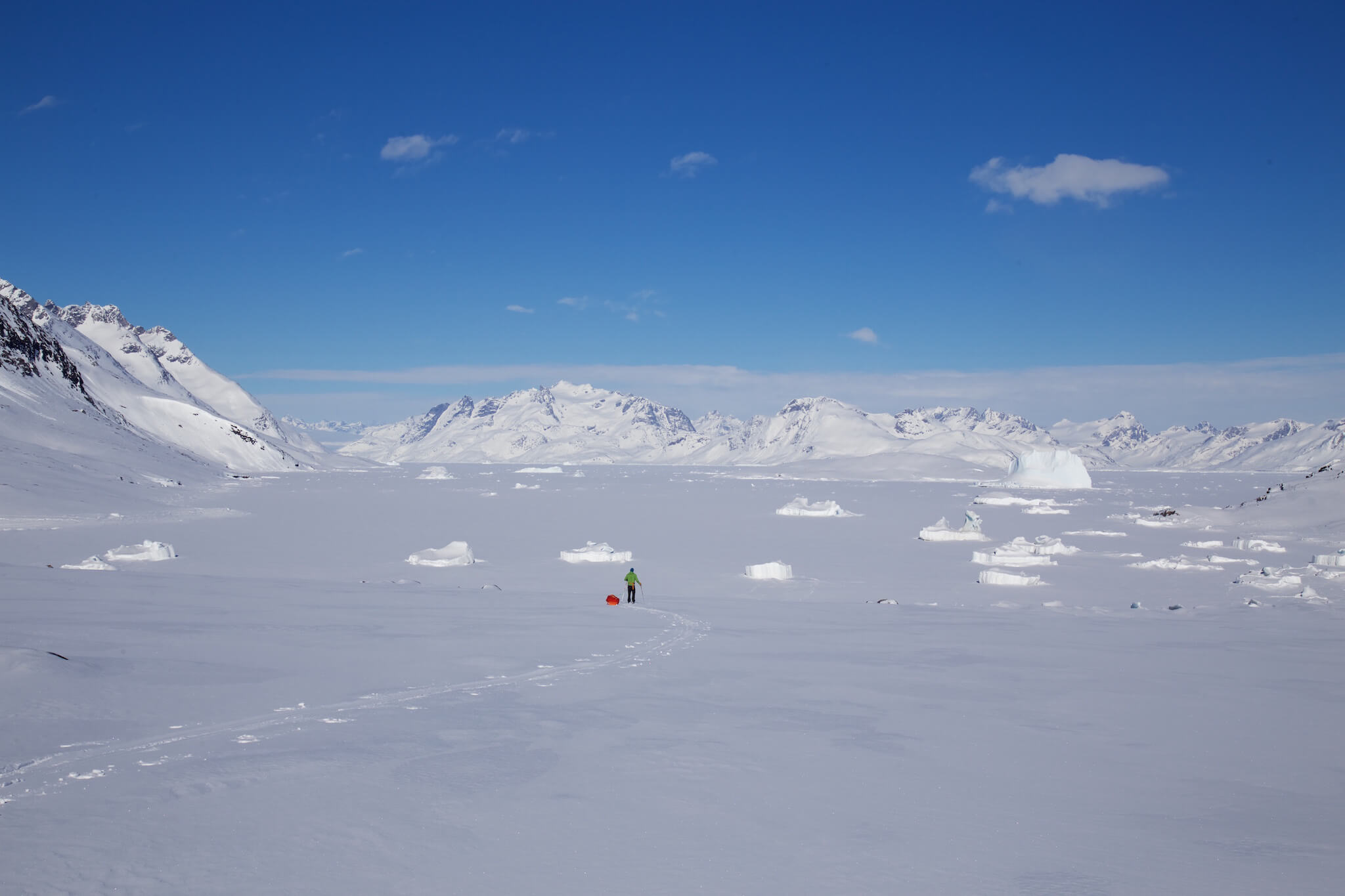

I’m amazed by the immaculate beauty of the environment in which I find myself.

The person in the lead, making the trail, has to redouble his efforts in the soft snow to pull the sled off the ice and make progress.

On Apusiaajik Island, as we do every evening, we build a wall of ice around the tents to protect ourselves from the wind, which can be very violent in Greenland.

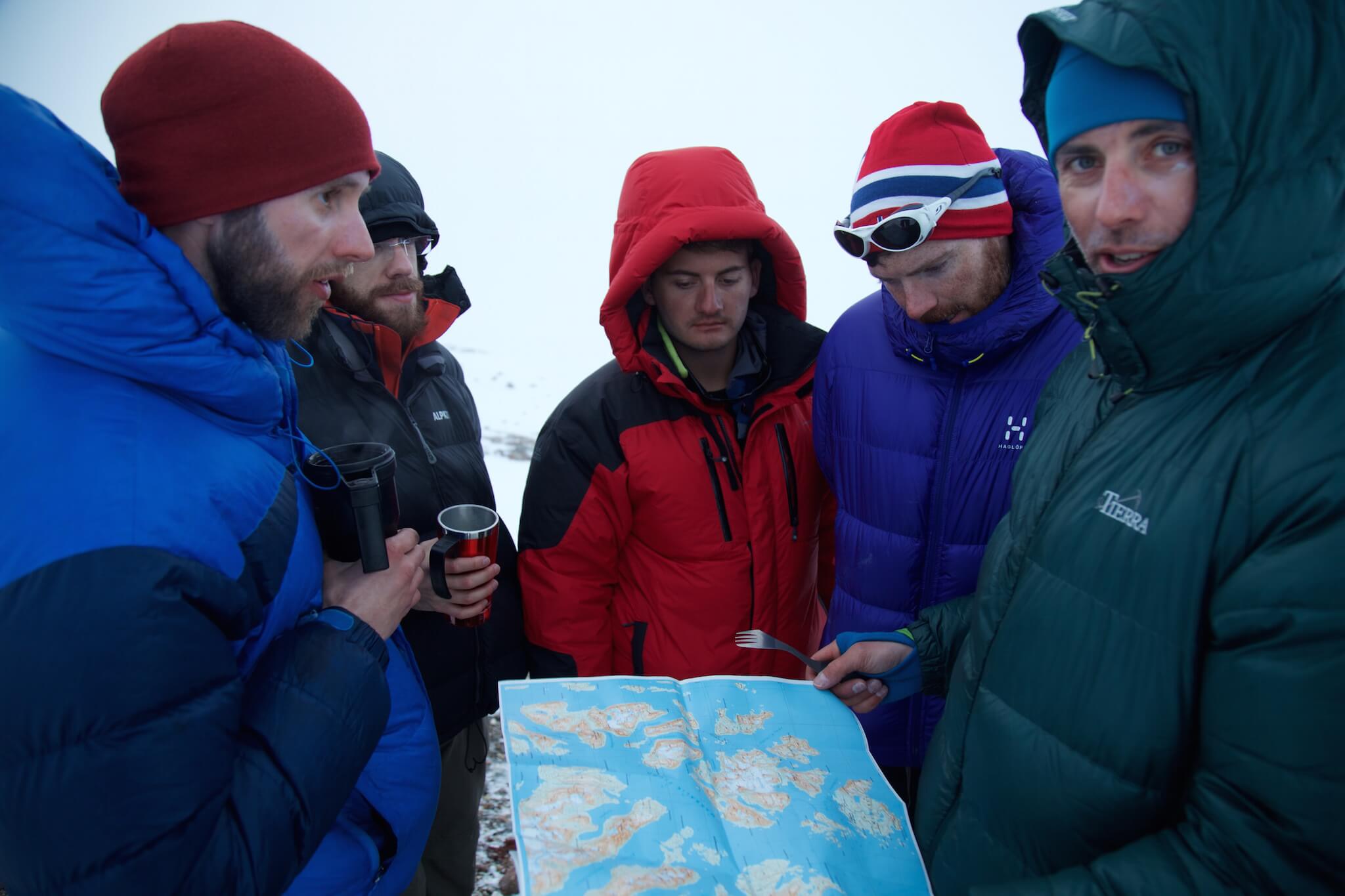

Richard, Noam, Ben, Luke and Christian prepare the next day’s itinerary (from left to right).

As soon as the sun goes down, the temperature drops considerably. To ward off the cold, it’s essential to multiply your layers of clothing.

At lunchtime, we eat crackers, cheese and dried fruit. In the evening, we have more time to rehydrate freeze-dried dishes, melting snow on our multi-fuel stoves. Here, 800 Kcal of chicken vegetable pasta.

As night fell, alerted by one of us, we got out of our comforters just before 10pm to observe for the first time the magical phenomenon of the aurora borealis. They are caused by the interaction between charged particles in the solar wind and the upper atmosphere.

When I’m leading the way, staring straight at the horizon, I feel a powerful sense of freedom.

We spend most of our time on the frozen fjords, camping on dry land. However, at this time of year, the ice is sometimes too thin to risk it, so we cut across an island and climb it to continue our journey.

Every evening, we set up 8 stakes around the camp, connected to each other by nylon wire. This device is a protection system against polar bears, of which there are many on the Greenland coast. If a bear were to approach our tents, it would trigger a series of detonations by pulling the wire as it moved. In the best-case scenario, the noise would cause the bear to flee instantly, otherwise it would put us on the alert. However, this protection technique is not infallible, and after dinner we systematically snow all our food in two pulkas, closed one on top of the other and tied together, close to the camp. We also do a “bear watch” every night, which consists of 2-hour shifts each to prevent any nocturnal visitors.

Like the katabatic winds in Antarctica, the region is also known for its very strong Piterak winds, which can reach speeds of over 300 km/h.

Under the gusts, we hurriedly set up camp, tying up anything left outside so as not to lose it: either blown away by the gusts or buried under the snow. We spent 36 hours trapped under the tent by the storm, getting out every two hours to clear the snow that the wind had piled on the tent despite our protective wall.

When we can, we set up camp early enough to climb to the top of the small mountains that surround us.

On these excursions, we leave our skis and pulkas behind, but don’t let go of our rifle in case of an encounter with a polar bear.

The mounds in the distance are icebergs waiting for the ice to melt and free themselves from the grip of the frozen sea.

On undulating terrain, we take off our skis more than once to climb the ridge. The deep snow, the steepness of the slope and the weight of the pulka make for a strenuous effort.

The terrain on Greenland’s east coast is by no means monotonous. Mountains, icebergs and open-water passages are all landmarks that the eye catches in order to move forward.

We walk between 6 and 8 hours a day. Each session lasts 50 minutes, at the end of which we take a few minutes’ break to eat before resuming the walk.

A hypnotic green canopy dances in the sky. While the formation of the aurora borealis is explained very rationally by science, it takes on a mystical dimension in these wild places, and transcends the observer.

Luke Robertson, a 30-year-old Scotsman with whom I shared a tent for half of the expedition. In January 2016, Luke became the first Scotsman and the second youngest ever to ski from the Antarctic coast (Hercules Inlet) to the South Pole, solo and without supplies. An expedition covering more than 1,130 kilometers over 40 days on the planet’s most hostile continent. Follow Luke’s adventures on his website www.lukerobertson.org

Christian Edelstam, our Swedish guide for the expedition.

After 11 days of expedition and 150 kilometers, we return to Kulusuk and look forward to a hot shower!

On the way back, the weather didn’t allow us to take off, so we waited 4 days for a lull before finally flying to Keflavík in Iceland.

Greenland, by far one of the wildest lands I’ve ever tread. I’ll be back.