IRAQI KURDISTAN

From Erbil to Iraq’s highest mountain

February 2017, Iraq is in the grip of violent fighting. West Mosul has not been liberated and is still in the hands of the jihadists. Kurdistan is an autonomous political entity in northern Iraq at the crossroads of Syria, Turkey and Iran. Security conditions there are stable, but clashes are close and minds are deeply scarred by the Sinjar massacres perpetrated by the Islamic State (EI) in August 2014. I haven’t prepared anything. I have no program for the next 9 days, other than to attempt an ascent of Mount Halgurd, the highest mountain in the country. I set off alone to say no to anything. To say yes to everything, as and when I met someone.

Flight PC374 to Erbil.

After a short stopover in Istanbul, I land in Erbil, the capital of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region. From the top of the citadel, you can see the central square. The surrounding alleyways are bustling with activity, with small restaurants, markets and terraced tearooms.

Erbil lies 80 km east of Mosul.

The citadel is the city’s historic center. The year of its foundation is not known, but it is believed to be the oldest in the world.

The atmosphere in Erbil is surprisingly calm. It’s strange and hard to imagine that the country is at war less than 100 km away.

I get lost in the markets. Curious about my presence, the Kurds ask me about the reasons for my trip and instantly invite me to join them for tea.

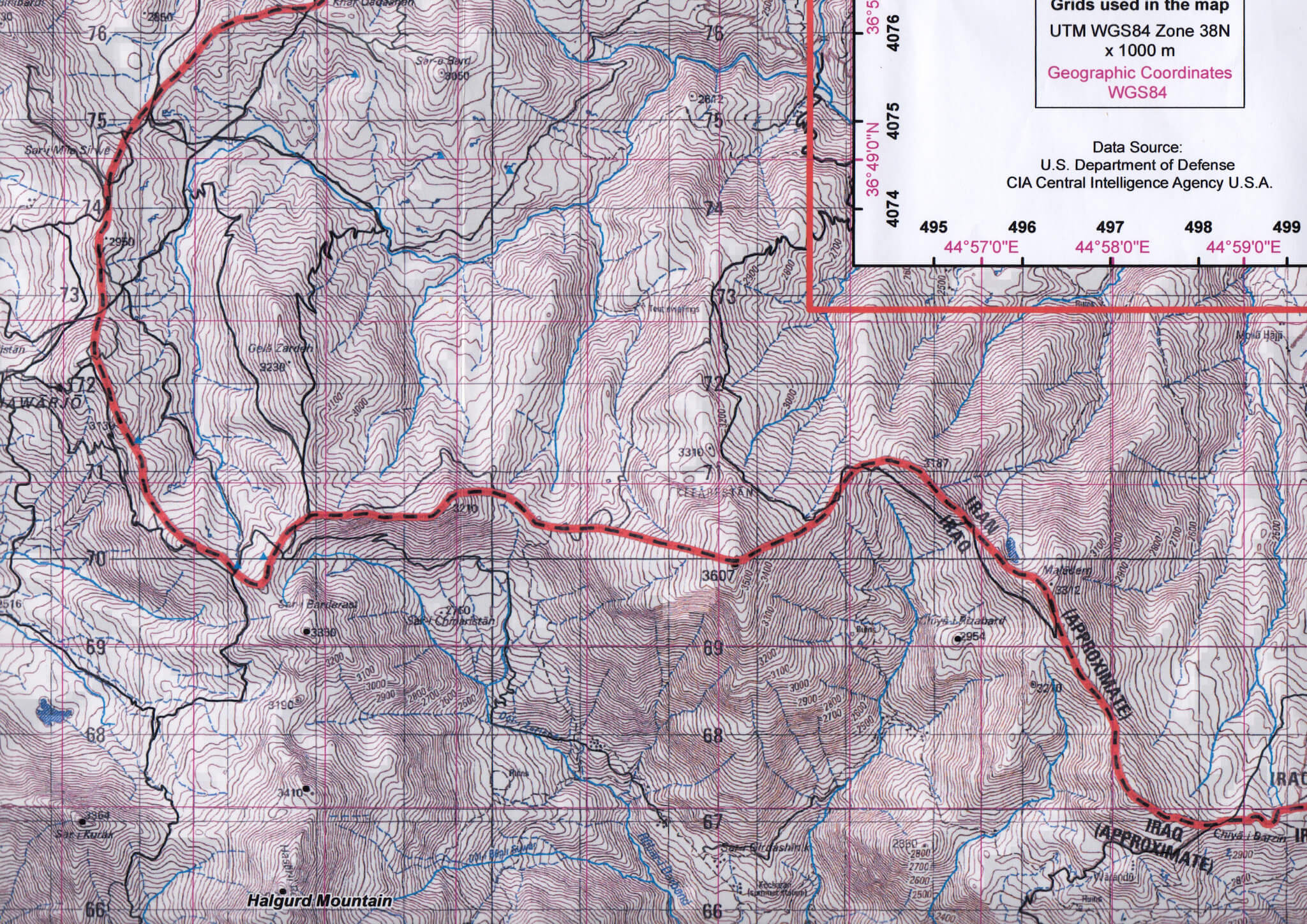

Military topographic map of the mountainous region of northern Iraq, a few kilometers from the border with Iran. From France, I contacted Salar, a local guide who agreed to accompany me to the summit of Mount Halgurd at an altitude of 3,607 metres. The climb isn’t particularly technical, but the area is mined and very isolated. Marcus, a 21-year-old Swedish traveler, is also in the area and interested in joining our little expedition. So, the three of us set off to conquer the mountain. Marcus Koehne

Off to Choman, the last town before the ascent of Mount Halgurd. I meet Hiwa in the cab we’ve been sharing since Erbil. When we arrive, he offers to put me up instead of letting me stay in a hotel. After a few courtesies, I accept and Salar and Marcus join us for tea and cakes. Hiwa is my age. He’s married and has a daughter. He tells us he just got out of prison, where he served a one-year sentence for possession of cannabis. In Iraqi Kurdistan, trafficking is severely repressed. Today he is unemployed.

The majority of houses in Kurdistan have no heating, but two large electric radiators heat the room. But it won’t be warm for long, as a power cut plunged us into darkness until morning. Throughout Kurdistan, power cuts are a daily occurrence.

Choman in the early morning. The weather looks good for the day.

Preparing for our little expedition. I leave everything superfluous with Salar, our guide, and take the essentials in my rucksack: crampons, ice axe, tent, sleeping bag, ground sheet, food for two days, stove, empty bottles…

In winter, the road to the start of the climb is blocked by snow. A friend of our guide takes us as high as possible in his 4×4.

We start climbing in the snow early in the morning. There’s not a soul around, we’re alone for miles around.

However, a few animals have left their mark.

We are self-sufficient in food and fill our bottles at the springs we come across. Here, the open water has dug a veritable well, which we bypass.

We slowly make our way up the mountain towards the base camp, from where we’ll set off for the summit.

As the sun sets, the temperature drops sharply. The harbinger of a cool night.

At the end of the day, we’re at just under 3,000 metres altitude. View of the road ahead.

We’re looking for a flat spot to pitch our tent before night falls.

After a day walking in the snow, our socks are inevitably wet and we try to dry them on our stove to make the next day’s departure a little more pleasant.

-20°C. It was a rough night. The socks didn’t dry and it took us an hour to warm up and put on our shoes, which were completely solidified by the ice. We knew the temperature was going to be low at this altitude. That’s why we opted for a 2-person tent for 3, to conserve as much heat as possible under the canvas.

It snowed all night. The fresh snow greatly compromises our chances of reaching the summit. We give it a try, but soon sink knee-deep. Sometimes we lose our footing altogether, slipping on patches of ice under the thick layer of freshly fallen snow. After a few hours, Salar turns to me and warns me of a possible avalanche risk. Visibility is poor.

We decide to turn back. In the mountains, only the descent is compulsory. I’m frustrated, but on the other hand, I know that if something were to happen to us on the mountainside, we’d be on our own, dozens of kilometers from any possible rescue. I reassure myself that in any case, even if we had reached the summit, the view would have been obstructed by snowfall and clouds.

The region bordering Iran was strategic during the war between the two countries in the 1980s. The barbed wire fences still in place bear witness to this period.

The mines are also numerous, and you need to know where to step.

Back to civilization, I leave Choman by cab. The easiest way to get around Iraq is to share a car. You can find them by going to “garaj cabs” in the center or on the outskirts of towns. From there, drivers wait to fill them up before starting their journey.

While waiting for new customers, a group of drivers take turns playing a game of chess.

Sadiq, by the gas stove, waits his turn to play.

Finally, a driver delivering a parcel for a customer picks me up for free, curious to chat with me. Although I saved about ten euros for a 2-hour journey, I could have done without the savings. The man beside me was driving like a madman between potholes. When we arrived, he asked me proudly: “What do you think of my driving? Relieved to be out of his death trap, I replied that I thought it was “fast”.

In Kurdistan, road checks are very frequent. I am regularly stopped at the entrances and exits of towns by the peshmergas (Kurdish fighters). The length of the interrogation varies. They check my identity, the reasons for my journey, the photos I’ve taken… With my few words of Kurdish and their few words of English, communication is sometimes difficult, but I’m allowed to go on my way freely.

The city of Duhok in northern Iraqi Kurdistan from my hotel room. In 9 days of travel, I only spent two nights in a hotel, thanks to the boundless hospitality of the Kurds and the kindness of friends of friends in the region.

A smiling kebab shop owner points to his employee and exclaims, “He’s Daesh! Laughter erupts throughout the restaurant at my incomprehension. His employee is Mossoulian. Faced with the EI, he fled the fighting and took refuge in Kurdistan. Even if today the Kurds are not directly threatened by the EI, the presence of the jihadists is on everyone’s mind.

Tea is served all day long. Any excuse is good enough to drink it.

On the road from Mosul to the Christian town of Alqosh.

With my driver, we pass one of the last checkpoints before Mosul held by the peshmergas. Their presence forms a thousand-kilometer defensive line around Iraqi Kurdistan to counter the expansion of the EI. Under the Kurdish flag, heroic portraits of fallen peshmergas can be seen.

View from the monastery of Rabban Hormizd in Alqosh. This Assyrian city is known as a hotbed of Eastern Christianity.

The monastery was founded in the 7th century on the rocky slope of a mountain. Today, it is open to visitors, but no one occupies it.

With the exception of a Christian Iraqi soldier guarding the premises. In 2014, the EI arrived within 2 km of Alqosh, causing the vast majority of the town’s inhabitants to flee for fear of being targeted. When I was there, you could hear from the top of the mountain the very regular coalition bombardments on Mosul, far away on the plain, some forty kilometers away.

The snow-white countryside around Amedi, in northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

In front of the flag of Kurdistan. Red represents Kurdish determination and fighting spirit, white symbolizes peace and prosperity, and green recalls the mountains and plains of Kurdistan. In the center, the 21-beam sun designates the Kurdish New Year, which takes place on March 21.

Kurdish cuisine consists mainly of charcoal-grilled meats served with rice and vegetables.

In Lalech, one of the holy places of Yezidism in northern Iraqi Kurdistan. This is one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions, whose followers were recently massacred by jihadists for being “devil worshippers”.

Lalech is home to the sacred temple of the Yezidis. Every believer must make a pilgrimage here at least once in his or her life. You walk barefoot to get closer to nature. The faithful kiss the door before stepping over it and entering the temple.

Yezidi religious buildings have conical roofs that symbolize the journey from earth to heaven.

During their visit to the temple, pilgrims perform a number of rituals, such as tying a knot in the colorful cloth that adorns the temple pillars. By tying a piece of cloth, they make a vow. Then they untie another to grant the wish of a previous devotee.

Their worship and rituals are transmitted orally, without the need for a prophet. That’s why you don’t become a Yezidi, you’re born one.

The number of Yezidis in Iraqi Kurdistan is estimated at between 100,000 and 600,000. But it’s difficult to count them, as they form a widely dispersed community. Some Yezidis live at the temple year-round. Like this man wearing the traditional khefieh.

They pray five times a day, with the morning prayer facing the sun.

For the Yezidis, fire is the incarnation of the sun on earth. The sun is sacred, and they worship it by lighting wicks with oil in front of every house every evening.

Very hospitable, I am invited to lunch by my hosts. We eat sitting on the floor on a mat in the common room, while the women eat in the kitchen.

All dishes are brought in at the same time, whether hot or cold, and served by the young boys of the house. Whereas we used to be very talkative, the meal takes place in silence. Several times, the best pieces of meat and brains are placed in front of me.

Conversation resumes once tea is served at the end of the meal.

Duhok at sunset. The city is surrounded by mountains and offers great hiking opportunities.

Bakery in Erbil. Men queue up to buy their bread. Circular and flat, it’s a staple food in Kurdistan. It is eaten at every meal and used to scoop food from dishes.

For my last few hours in Erbil, I decide to spend the evening in a “tchaikhane”, a popular tea room. On TV, the latest news from the front in Mosul is broadcast over and over again.

Curious to exchange ideas, my neighbors and I found an English-Kurdish dictionary that enabled us to communicate.

My two interlocutors are opera singers. Before the war, they were able to perform abroad; today it’s more difficult.

Customers come and go, and I’m quickly accepted by them, although my presence at this late hour is unusual. I spend the evening drinking tea. As I leave, the owner I’ve made friends with refuses to take my money.

Erbil International Airport. Back to Paris after a week of meetings, photos and exchanges.

When I left Paris, the border police asked me many questions about my reasons for going to Iraq. But it’s not difficult to visit Kurdistan. For stays of less than 30 days, a tourist visa is issued on arrival.

During my visit, I experienced once again the incredible hospitality and generosity of the Middle East (see my trip to Iran in 4L, Un tour du monde du microcrédit). Despite the tragedy of war and the murderous madness of the EI at the gates of Iraqi Kurdistan, I met a proud, serene and curious Kurdish people who gave me a new vision of the land of two rivers.