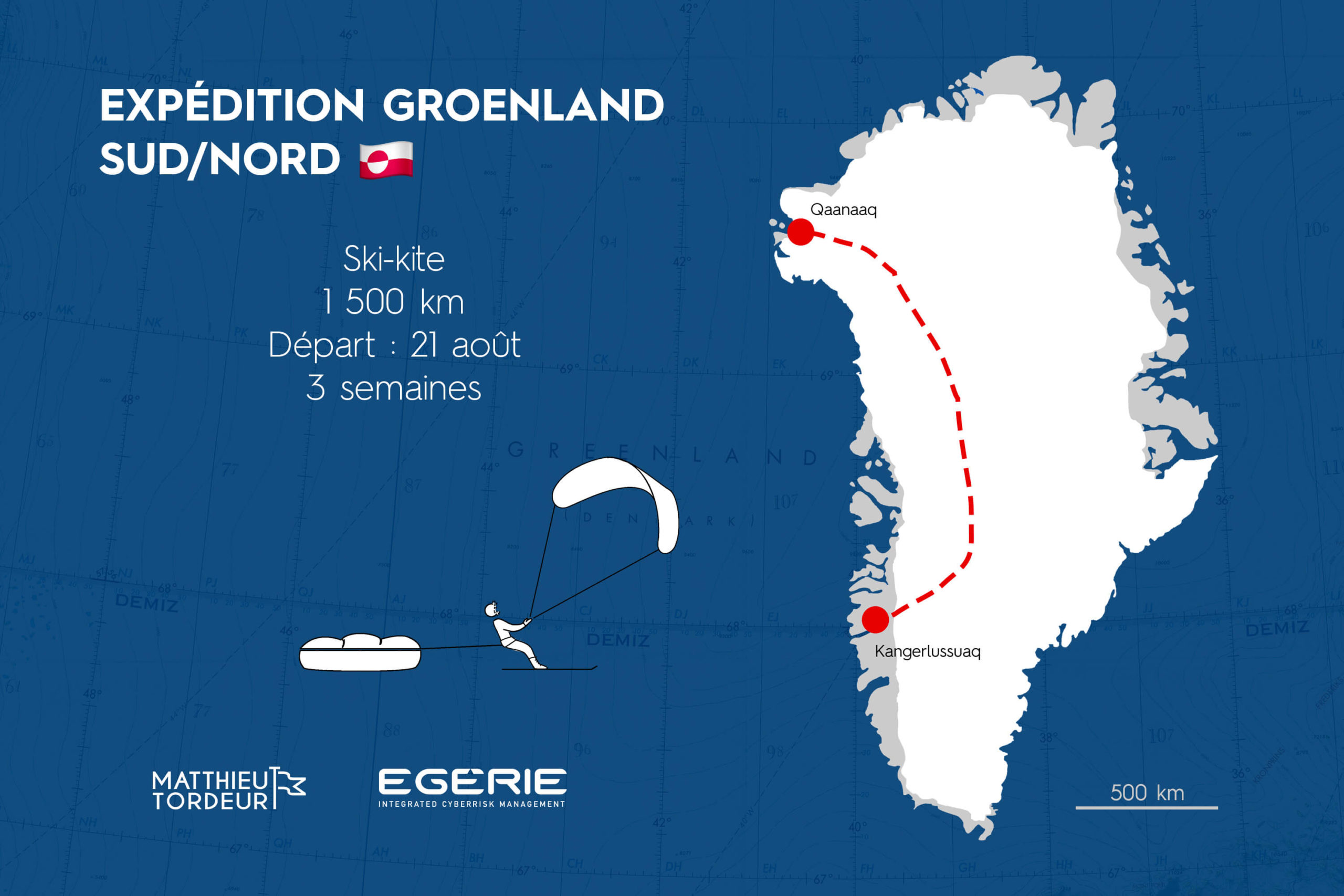

SNOWKITING IN GREENLAND

From Kangerlussuaq to Upernavik

August 21, 2020. In this strange time of pandemic, I have the opportunity to join an expedition at the drop of a hat with Dixie Dansercoer, one of the best polar kiters in the world.

Together with Cordula and Lorenz, two other Swiss adventurers, we’re going to attempt to cross Greenland from south to north by kite-ski, at the mercy of the katabatic winds. From Kangerlussuaq to Qaanaaq, over 1,500 kilometers of autonomous travel on the world’s largest glacier after Antarctica.

We plan to spend 3 weeks travelling from Kangerlussuaq to Qaanaaq by kite-ski. Our speed will depend on wind and terrain.

Right up to the end, we feared we wouldn’t be able to get on the plane. In August 2020, the pandemic is making it very difficult to travel abroad. Even more so in Greenland, where hospital services are limited. After a long wait and endless administrative formalities, we are one of the only expeditions of the year to Greenland.

As we leave the plane at Kangerlussuaq airport, we gather all our belongings, relieved to be on Greenlandic soil at last. This is my second time here. As for Dixie, he’s lost count of the number of expeditions he’s made here.

We take up residence in a hostel that only we occupy. Now it’s time to get our sleds, food and equipment ready, before we reach the polar cap and begin our expedition in a few days’ time.

It’s the big day! We are dropped off by car at the end of the road leading to the polar cap. Along the way, we come across musk oxen, arctic hares and reindeer. It’s as if the animal kingdom is greeting us before we enter the great polar desert.

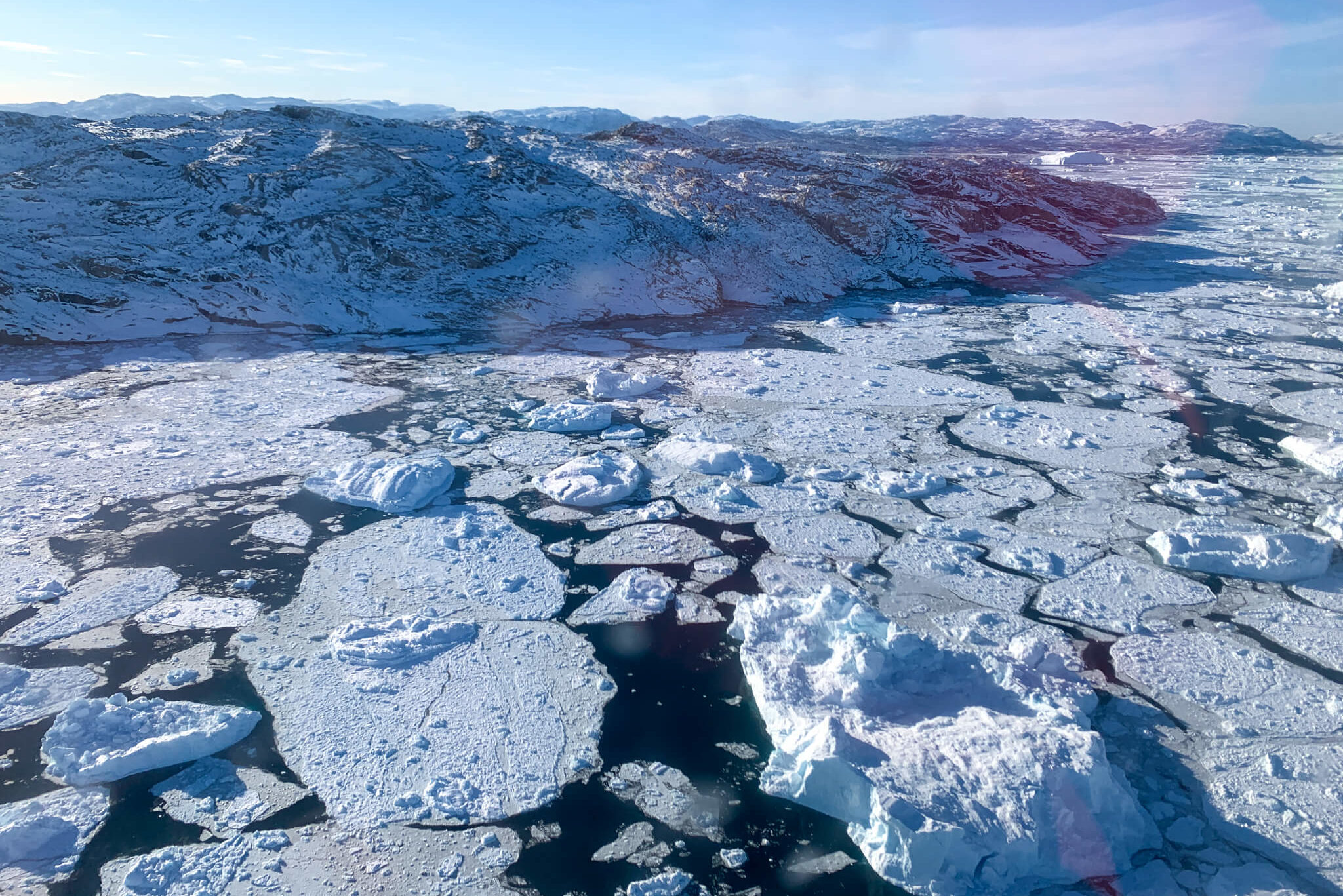

The lower part of the glacier is very uneven, dried out by the sun that has warmed it all summer. Ahead of us is a terrain bristling with ridges, peaks, crevasses and steep passages. We first have to make our way through this ice chaos on foot, and then patiently get out our kites.

My sled weighs 110 kg. It’s so heavy and bulky that I have to bend over with all my weight and push with all my might to tip it over the ridges. When it’s balanced on the ridge, I have to scramble down the slope, avoiding the water holes, and the sled coming up fast on my heels.

Rivers of meltwater cut through the ice. With global warming, the polar ice cap is now melting at an alarming rate. Greenland is an island (4 times the size of France), covered in ice and snow. This ice, which is “land ice”, melts around its perimeter and flows into the sea. It is precisely this ice that causes sea levels to rise. If the whole of Greenland melted, sea levels would rise by 7 meters, directly threatening our coastlines.

In the evening, we try to find a more or less flat spot to set up camp. The terrain we find ourselves on is so fragmented that we’ve only progressed 2 kilometers in 9 hours of effort.

We’re moving at a snail’s pace, but I’m delighted to be discovering this part of the world and immersing myself in expedition life once again. The view from the tent I’m sharing with Dixie announces the program to come. The next few days will be challenging, but the further we go, the flatter the glacier will become.

In late summer, the glacier is not at all in the same condition as it was in May, when this expedition was planned but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In spring, the terrain is less rugged and it takes around 5 days to reach a flat area of ice where you can kite-ski. At the end of August, we often find ourselves facing walls. With crampons on, two of us have to pull and push the pulkas.

During the day, we spend a lot of energy pulling the pulkas. So when there’s a ray of sunshine, I take the opportunity to break the ice and wash up briefly in a water hole. I once went more than 60 days without showering (during my South Pole expedition in 2018-19) and I have no ambition to come close to this record.

In this labyrinth of canyons and cracks, meltwater forms little pools of blue water. This is often the easiest way through the chaos of ice bumps, especially as we can float our pulkas in it. But you have to be careful: water is a friend that doesn’t do you any favors in these polar regions.

We spend a good part of our days looking for the best passage through the ice. We often unhook ourselves from our pulkas to climb a boulder and read the terrain ahead.

At the bivouac, we dry out our gear, soaked by our time in the water. We carry a rifle to defend ourselves in the event of a polar bear attack. Logically, we shouldn’t come across any: they spend most of their time near the ocean, where they can feed. In addition to the rifle, we also carry smoke bombs, which are of course used as a last resort. The terrain is still very difficult and we’re making progress at a rate of 250 metres per hour, which isn’t enough.

At the rate we’re progressing, it would take us about 2 weeks to find flat ground. Our goal on this expedition is to kite. Not to climb the glacier and do 2 km a day. Our time is limited by the food we’ve brought with us and the weekly flight from Qaanaaq back down south. After 5 days, we reluctantly decide to call a helicopter to get us past the glacier’s tension zone.

All the equipment is transported in a net and we are deposited on the polar cap after a 20-minute flight at an altitude of 1,300 meters.

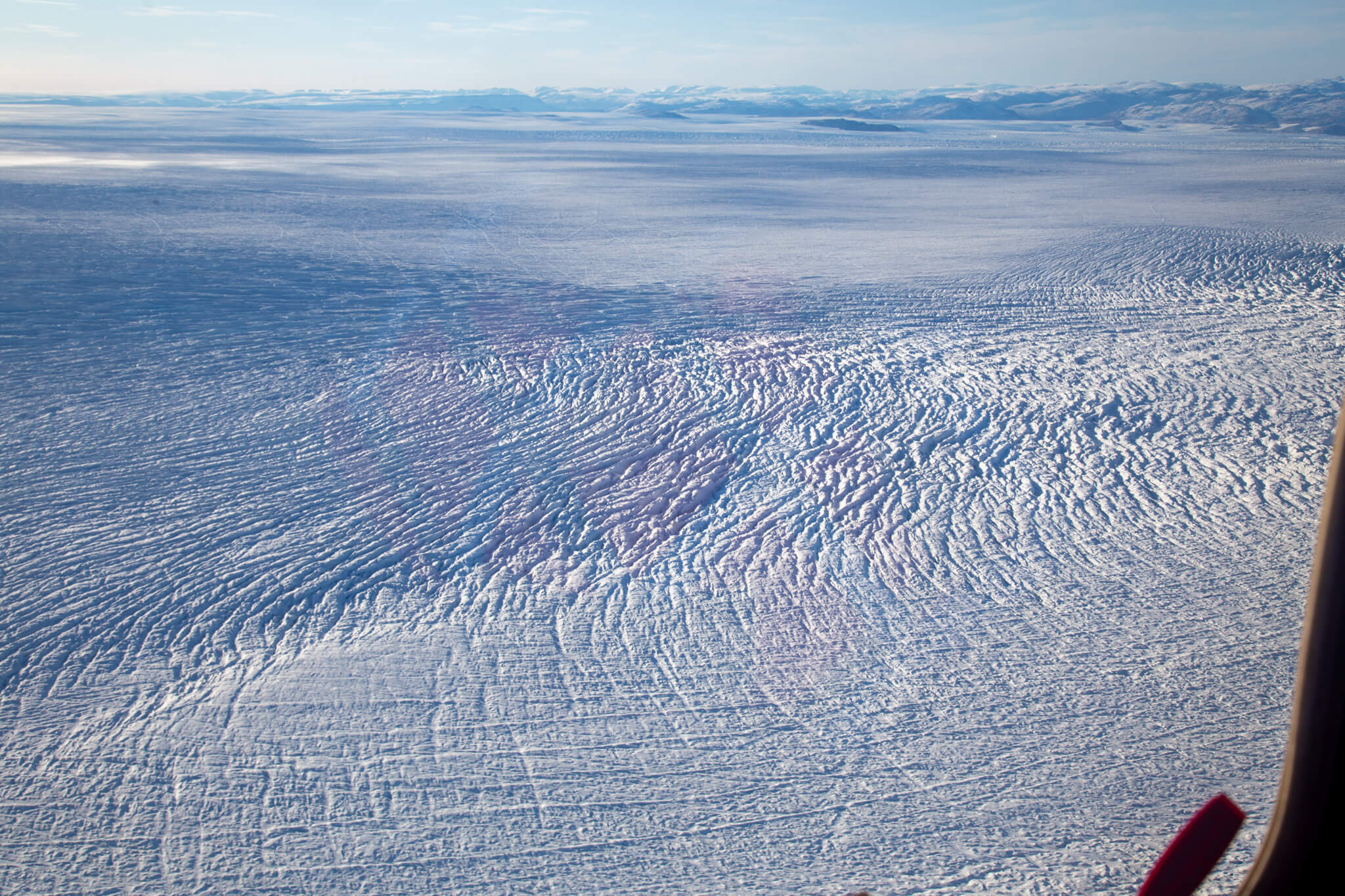

From the helicopter, we first glimpse the impassable chaos of ice ridges, then the blue rivers that criss-cross the surface – relieved to cross them with such ease.

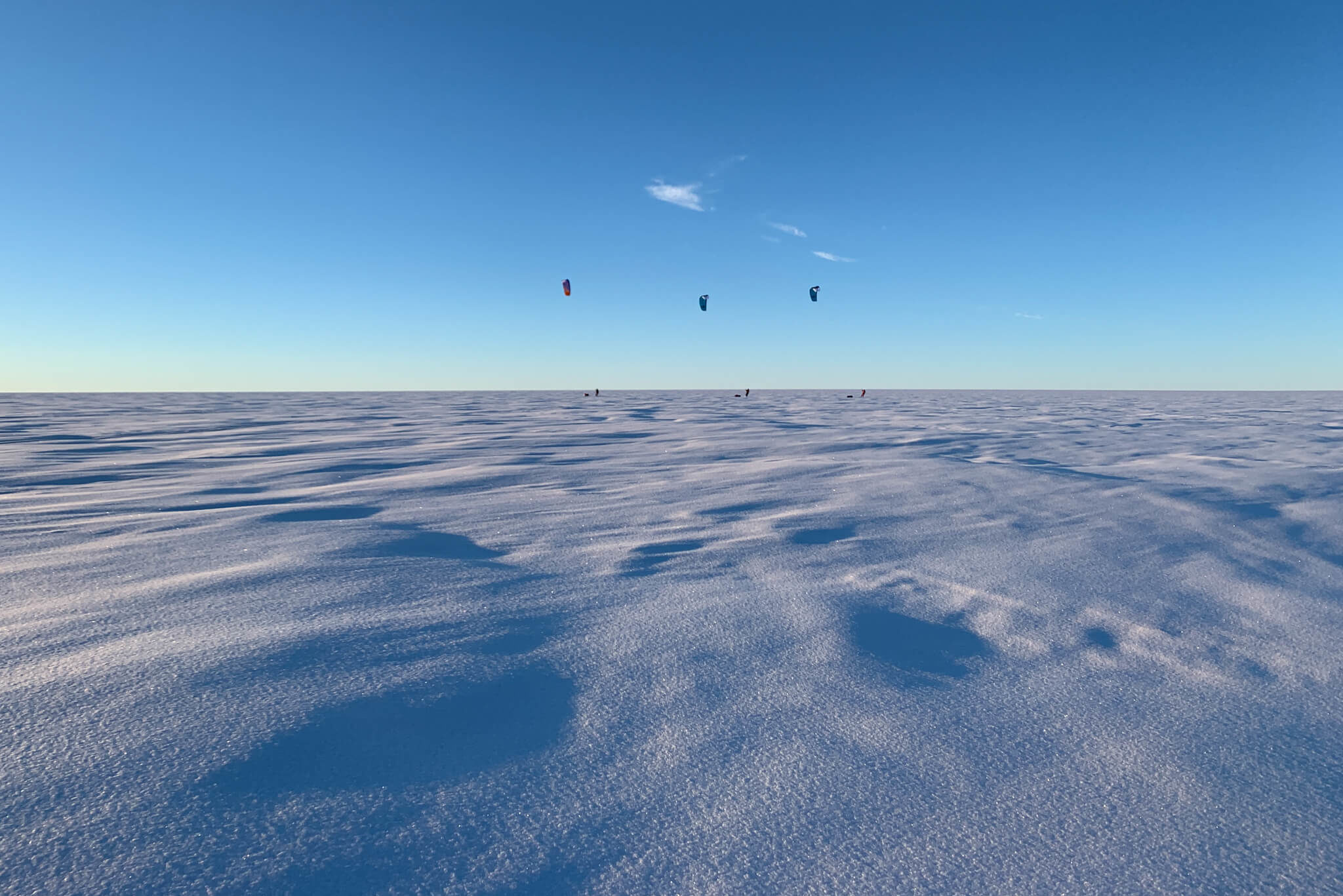

Flat ground at last! After rearranging our sleds, we send our 18-square-meter kites into the air and mark the immaculate snow with our skis.

Perfect conditions to start the expedition: flat surface, 100% visibility, moderate wind. We’re on our way!

I follow Dixie closely as she leads the way. Our smiles beneath our masks and helmets speak volumes about how happy we are to be here.

We make our sails dance in the sky. In light winds, we have to turn the kites, describing arcs, figure-eights and circles in the air… This gives them power to pull us and our 100-kilo sleds northwards.

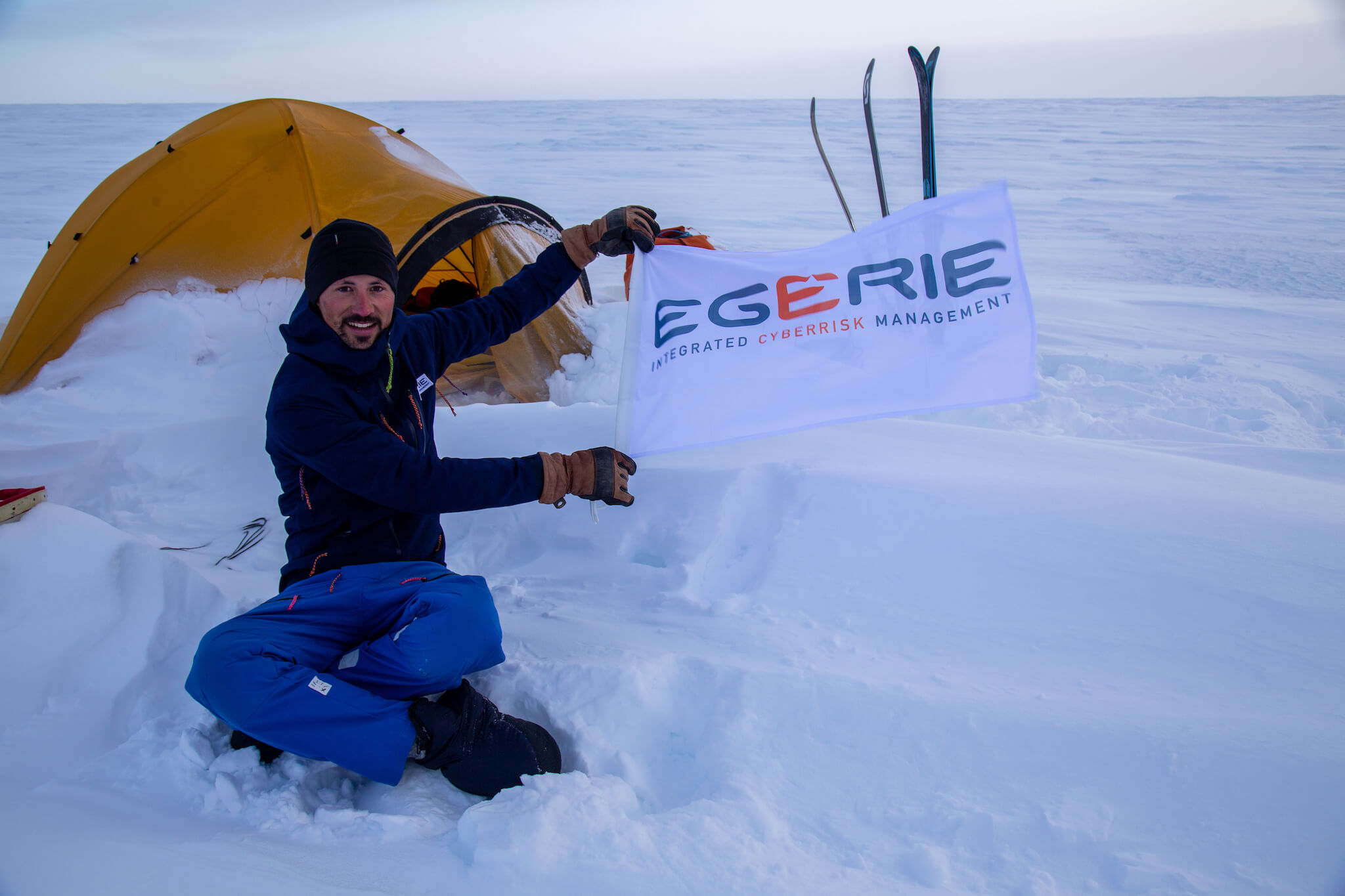

EGERIE Software, a specialist in cybersecurity, is the sponsor of my expedition. The management team immediately recognized themselves in my Greenland expedition, because we share a conviction: anticipating risk is already mastering it! Thank you EGERIE for your confidence.

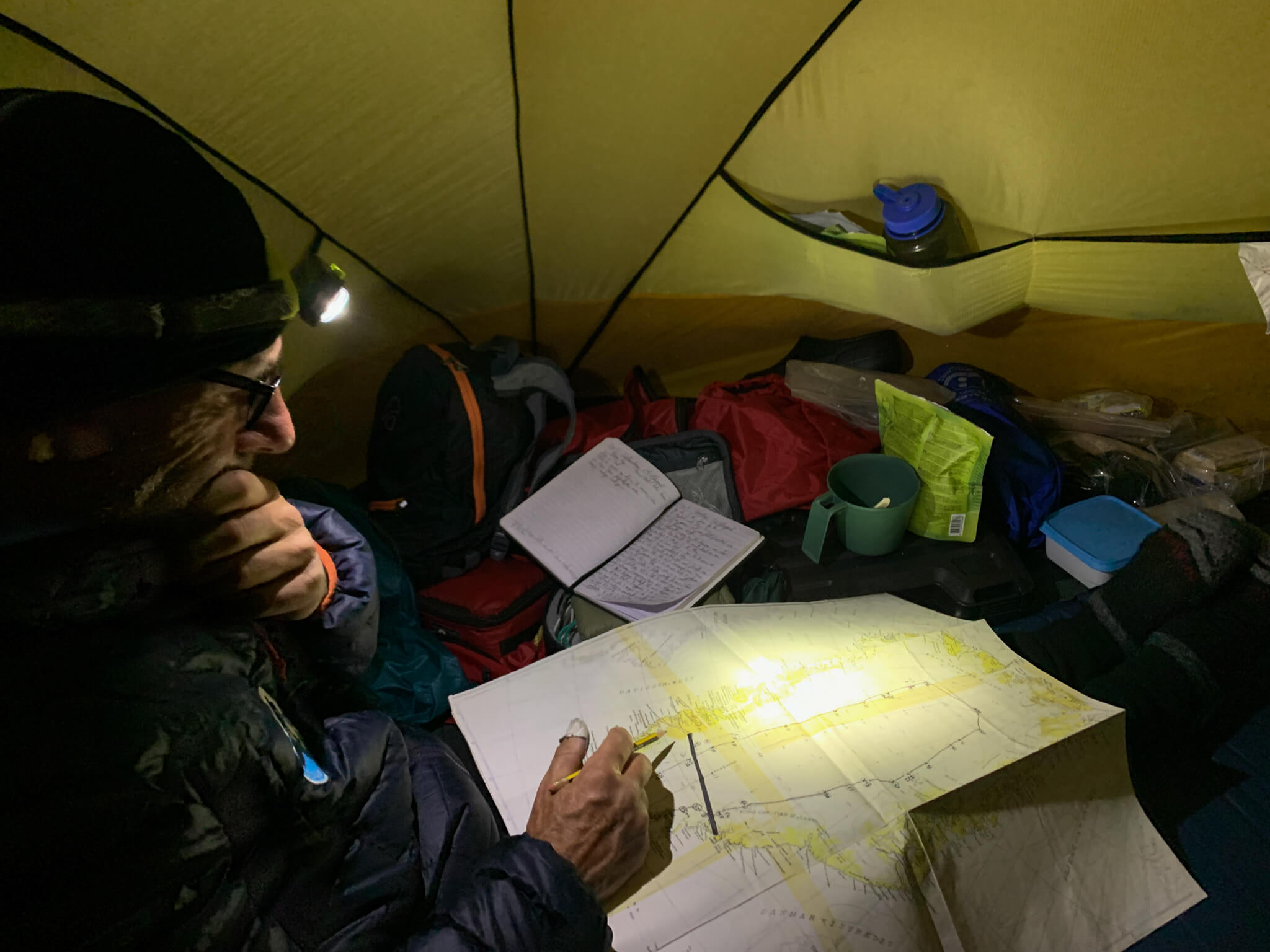

In the tent after a day’s kiteboarding, Dixie plots our position on his Greenland map. The map shows the route he and Eric McNair-Landry took around Greenland in kite-skiing in 2014 (55 days). Dixie is certainly the world’s most accomplished kite-skier, and he confided to me with a smile that by the end of our expedition he will have kite-skied 20,000 km in the polar zones.

We sometimes kit until sunset. We’re still lucky enough to have a few hours of night at this latitude (N68°). You have to make the most of the conditions while they’re here. The lights on the ice are sublime.

In kite-skiing, we need both wind and visibility. Sometimes the wind gusts make it impossible to move forward. The gusts lift the surface snow, covering our sleds and settling around the tent as if to bury it.

When the wind drops, it sometimes gives way to whiteout, an optical atmospheric phenomenon that cancels out all sense of space, depth and relief. So we’re forced to stay in our tents, sometimes for days on end. Cordula and Dixie pass the time by doing laps around our camp on cross-country skis and running.

Sails down, we groped our way forward. Reduced visibility means we have to proceed vigilantly, in single file. We stay together, in constant visual contact. We each carry a satellite phone, just in case. When visibility becomes zero, we stop, either with our sails in the air, or with our sails on the ground, to wait for conditions to improve.

The sky almost merges with the surface. Only the sun occasionally breaks through the opaque clouds. “It’s a strange world”, says Dixie when I reach her height. We are indeed in a polar desert open to the winds, where only ice reigns. It’s both sublime and inhuman.

It’s a magical feeling to zip along on skis, leaning back in your harness at between 15 and 30 km/h towards the horizon.

Due to the lack of visibility, we take an enforced break to warm up, eat and drink. With four of us, it’s always a bit of a hassle to land the kites, secure them and get away safely. So when the weather’s good, we only take two or three in a day.

The first time I met Dixie was when he called to congratulate me on my solo expedition to Antarctica in 2019. I was very touched to hear from someone I admired so much. I immediately connected with his jovial and enthusiastic temperament. We trusted each other very quickly, and it was a great privilege to spend so much time with him.

Gusts of wind of up to 90 km/h keep us on the spot. Huddled in our sleeping bags, we can feel the force of the wind drowning out our voices and reducing our conversations at the same time. We still go out in the afternoon to collect food from our sleds and fuel for our stove. Faced with the wind, the cold is instantaneous and brutal. It’s impossible to face it with your eyes open. We spend a few minutes running around the tents to warm up and take a few pictures. It’s frustrating to be assigned to stand still, but when conditions aren’t right, we have no choice. There are variables we can influence: skiing longer, more efficiently, but we certainly can’t control the weather.

After 48 hours of waiting, we can finally set off again. But there’s no need to rush: before each departure, we have to conscientiously unfold the kite and make sure the lines aren’t tangled.

The terrain is very favourable and we’re speeding along, clocking up a record 142 km in one day!

It’s a great feeling to be pulled along by the wind, to choose your path on the ice by waving your sail in the air.

At an altitude of over 2,000 m, the temperature is getting cooler and cooler. We have to add a layer and put on the big mittens. With the wind, the temperature feels much colder than -20°C. It’s mainly the left hand that suffers. It’s the one that holds the bar of the kite, but being in the air, the blood doesn’t circulate as well.

A few days ago, we changed course. We’re heading much further west, towards the coast. In view of the bad weather, the delay and our dwindling food rations, my expedition companions Cordula and Lorenz have decided to stop in Upernavik for professional reasons. It’s the only village with an airport before Qaanaaq, far to the north.

We stopped 94 km as the crow flies from Upernavik, stuck in a bowl surrounded by crevasses. We crossed a dozen of them on snow bridges. It would have been dangerous to continue. Upernavik is located on an island, far from the coast. Once again, we had to call in a helicopter. Had we been able to follow the original route to Qaanaaq, we would have had to descend the glacier (more practicable to the north), then be picked up by dog sled or boat to reach the village. Unfortunately, we don’t have that option here.

At 4 o’clock in the morning, Cordula and Lorenz were surprised when their tent collapsed in on itself. Not being positioned exactly in line with the wind, they then undertook the perilous but necessary operation of moving it, headlamp on. In the morning, Lorenz defied the gusts to come and visit us, and collapsed in our tent after battling against the elements. The three of us, stunned by our misfortune, laugh out loud at the violence of the storm. From now on, we’ll have to be patient, count our food and evacuate at the first weather window. Adventure is adventure!

Patience, patience… Every day we wait for the weather to improve so that Air Greenland can take off and pick us up. But the sky is not cooperating. So we pass the time with Dixie by playing Yatzi, a game of chance with dice. It consists of making combinations to obtain the most points possible. The scores are close!

Good news as we awoke from our seventh day of waiting. Air Greenland attempts a flight. In 30 minutes, we’re ready to go. It’s windy, but visibility is very clear. From the airstrip we’ve spotted, we scan the sky, impatient… At the appointed time, a black dot suddenly appears! It’s them! The huge helicopter flies over us once to scout the area. Then it lands with its two pilots on board. Snow flies in every direction. We’re relieved to see them here.

Smiles on our faces after 6 and a half days in our tents. We were picked up by Air Greenland after almost a week of interminable waiting and two aborted attempts, one of which was 9.25 km from our position.

I’m not in favor of using helicopters for everything, but in our situation, on this very crevassed part of the glacier and with no other way of reaching Upernavik, we had little choice. Air Greenland did their utmost to get us back as quickly as possible, but were confronted with capricious weather (as we have been since the start of this expedition).

In the back of Air Greenland’s Bell 212 helicopter. The end of the adventure. Not quite as I’d imagined it, but that’s what adventures are for.

As we approach Upernavik, it’s time for a shower, fresh food and the joys of returning to civilization.

Upernavik

The town of Upernavik, home to just over 1,000 people.

Large icebergs can be seen drifting from the shore.

The town is quiet. There’s a very communal atmosphere, as everyone knows everyone else.

There’s only one flight a week back to southern Greenland and then France. So we take advantage of our free time to go kayaking to see the icebergs.

Traditionally, house colors were used to identify their function: green buildings were for administration, yellow for medical staff, blue for technical trades and red for the church.

From the airplane window, I gaze at the coast and the drifting ice, dreaming of new adventures.

“In adventure, nothing must be left to the unforeseen, but everything is unforeseeable”. Paul-Émile Victor, famous French polar explorer and ethnologist, had this saying, which illustrates our expedition quite well.

All in all, we stayed in tents for 1 day out of 3, unable to make any headway due to poor weather conditions. The Swiss’ request to return to Upernavik took us off course and would have required a lot of effort and time to climb back up. Naturally, I’m disappointed not to have gone all the way, but continuing to Qaanaaq would have meant counting on excellent conditions.

My main aim in taking part in this last-minute guided expedition was to perfect my kite-skiing. With 800 km covered in both good and bad winds, I’ve done just that. And it’s already giving me ideas for new expeditions.

Many thanks to EGERIE Software for their support and to Expeditions Unlimited for the logistics.

See the interactive map of our adventure on LiveXplorer.

On June 7, 2021, one year after our expedition, Dixie fell into a crevasse 250 km north of Upernavik in Greenland. Unfortunately, his body could not be found after rescue operations. He left us doing what he loved best. He was a man of rare humility and kindness – as well as being one of the best polar guides in the world. I’ll always remember the 35 days I spent snowkiting with him on the Greenland ice cap. Dixie was a mentor and a friend. We had plans to go on expeditions together. I feel privileged to have crossed his path and at the same time orphaned by an extraordinary teammate. Dixie, my friend, you are dearly missed!

The publication of this article comes a year after Dixie’s death. It’s hard to catch up on writing after such a tragic event. My thoughts are with his wife, children and loved ones.