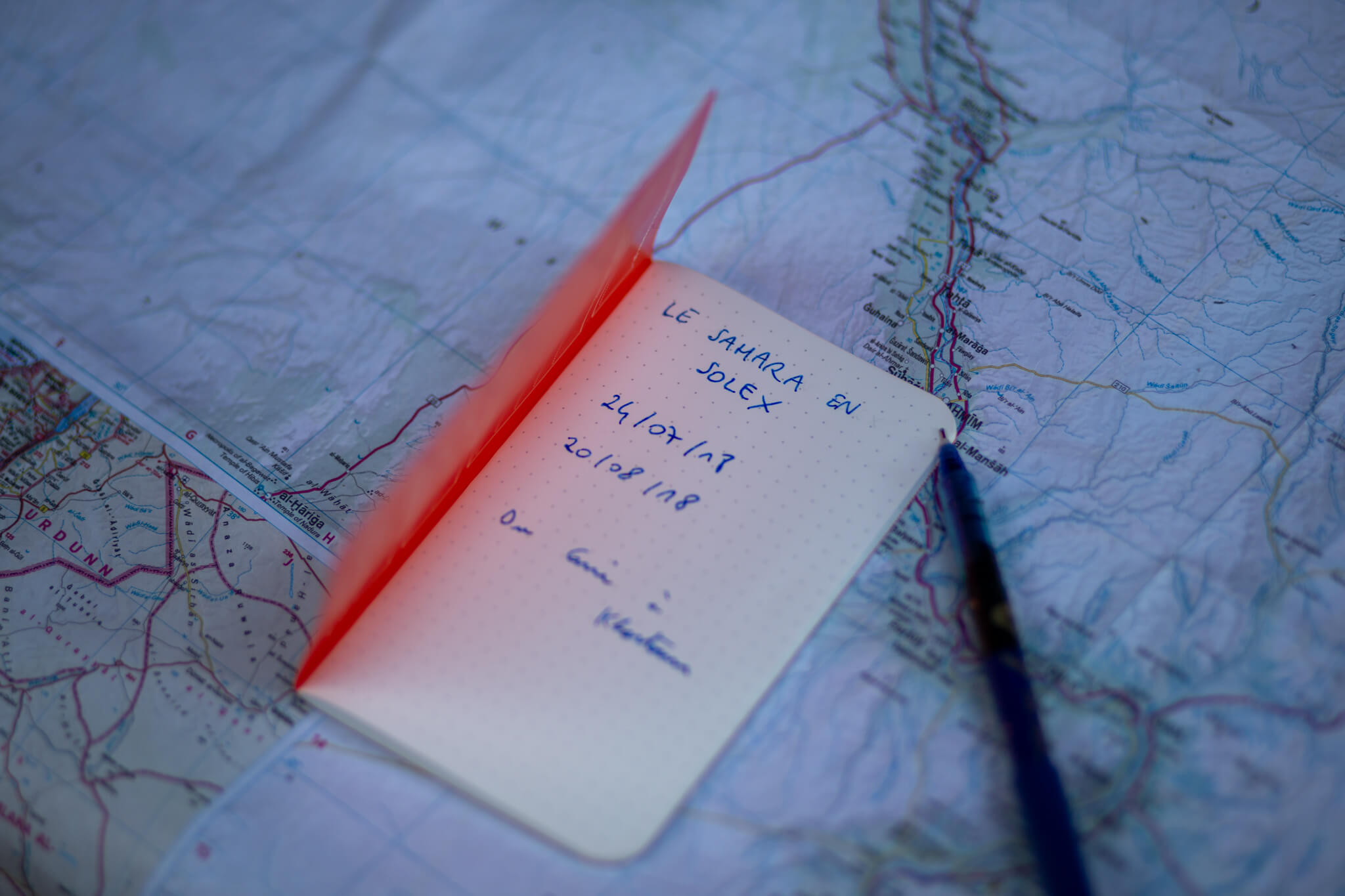

THE SAHARA BY SOLEX

Along the Nile on an electric bike

Back in July 2014, I crossed the Sahara with my childhood friend Nicolas. At the time, we were between Senegal and Morocco at the wheel of a 4L, on the verge of completing a circumnavigation of over 50,000 kilometers.

Four years later, we’re heading for the other side of the Sahara. We’ll be crossing the Sahara from north to south along the Nile. No camel caravan to accompany us, but two electric bikes to cover the 2,400 kilometers between Cairo in Egypt and Khartoum in Sudan.

Resolutely modern, our adventure is a life-size test of a “soft” form of mobility in a harsh desert. The Nile will be our guiding river, source of life and cradle of a civilization thousands of years old. We’ll pedal our way past electrical outlets, temples and pyramids. Welcome to the kingdom of the pharaohs and the Nubian desert.

– EGYPT –

From Cairo to Abu Simbel

Our adventure begins in Cairo, Egypt, from where we map out our route to the Sudanese border.

We’re leaving in the middle of summer 2018. On the face of it, this is the worst time to go to the Sahara, but it’s the only time Nicolas can free up 4 weeks in a row.

For this adventure, we have entered into a partnership with Easybike. We’ll be using two Solex electric bikes to get to Khartoum.

The famous pyramids of Giza are located some 20 km from Cairo. It’s hard to visit Egypt without seeing them. When we see them, we can’t help but think of the great archaeologists, Tintin and certain masterpieces of French cinema.

The pyramids stand in the desert on the edge of town.

We leave our bikes outside the site. We then approach the pyramids on horseback and camelback. Since the Egyptian revolution in 2011, the country has struggled to attract foreign visitors, and the site is empty of tourists, much to the chagrin of those involved in the industry.

We make a detour to Djoser’s funerary complex at Saqqara. Here, the southeastern entrance to the enclosure.

We continue our journey on our electric bikes. In two panniers fixed to our luggage racks, we carry everything we need for the next month’s itinerary. We’ve opted not to camp and to stop in the many guesthouses along the Nile. We ride in our shirts. This may seem a surprising choice, but it’s extremely hot at this time of year. Shirts have many advantages. You can adjust the collar and sleeve length according to the time of day to protect yourself from the sun. And if you choose a shirt that’s loose enough, it dries very quickly, and the wind that rushes in makes it feel cooler.

We stop off in medium-sized towns. Here in Beni Suef, we take refuge in a hotel overlooking the city’s rooftops. At sunset, the muezzin’s call to prayer echoes throughout the town.

In the evenings, the cafés are lively. Tea is drunk, hookahs are smoked and “taoula” (Egyptian backgammon) is played. They are frequented only by men, as is often the case in public places in Egypt.

A traditional felucca on the river at Al-Minya. Seen from the air, Egypt is a vast arid desert scarred by a green vein through which flows the waters of the Nile. Its annual flood deposits silt that fertilizes the soil and fills reservoirs for irrigation. The Nile plays a key role in agriculture and livestock breeding. Most of Egypt’s population is concentrated on its banks.

The police are everywhere on our route. Checkpoints abound. A team of policemen accompanies us to visit the Coptic monastery of Deir el-Muharraq, just off the road.

It is one of the oldest operational Coptic monasteries in the world (4th century) and the most sacred place for the Copts of Egypt. In a population that is 90% Muslim, they are in the extreme minority.

Within the monastery grounds are a covered market and tea stalls. We are welcomed with open arms by the faithful and pilgrims.

The monk Philippe in charge of the guest house gives us the tour.

Inside the Temple of Amun in Luxor. A 3500-year-old jewel of ancient Egypt, we marvel at the power of this civilization.

The Temple of Karnak in the early morning. The obelisk in the photo bears a striking resemblance to the one that once stood in the Temple of Amun and was presented to French King Charles X in 1830 as a sign of goodwill. It is now enthroned on the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

Inside the temple, the guard mischievously points out the best photo vantage points.

Nile, Nile, Nile. With a length of some 6,700 kilometers, it is, along with the Amazon, the longest river in the world. We’ll be following it all the way to Khartoum, where it has two tributaries: the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which have their source even further south.

As of July 2018, the western half of Egypt is classified as red by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, i.e. formally inadvisable for visitors . The western desert near Libya is a high-risk area plagued by traffickers and terrorism. The eastern half of the country, where we are located, is calmer, although it is advisable to remain vigilant.

As a result, there are numerous police checkpoints all along the Nile. We are assigned police escorts between each checkpoint, with no possibility of refusing them. We never get any concrete explanation for these escorts. It would seem that the region is under control, but that tourists must be given special attention to avoid any incidents.

The Temple of Horus at Edfu. This is one of the best-preserved monuments of antiquity. The temple overlooks an open-air courtyard surrounded by porticoes.

At the end of the day, the light shines through the interior of the temple, highlighting the hieroglyphs on the wall.

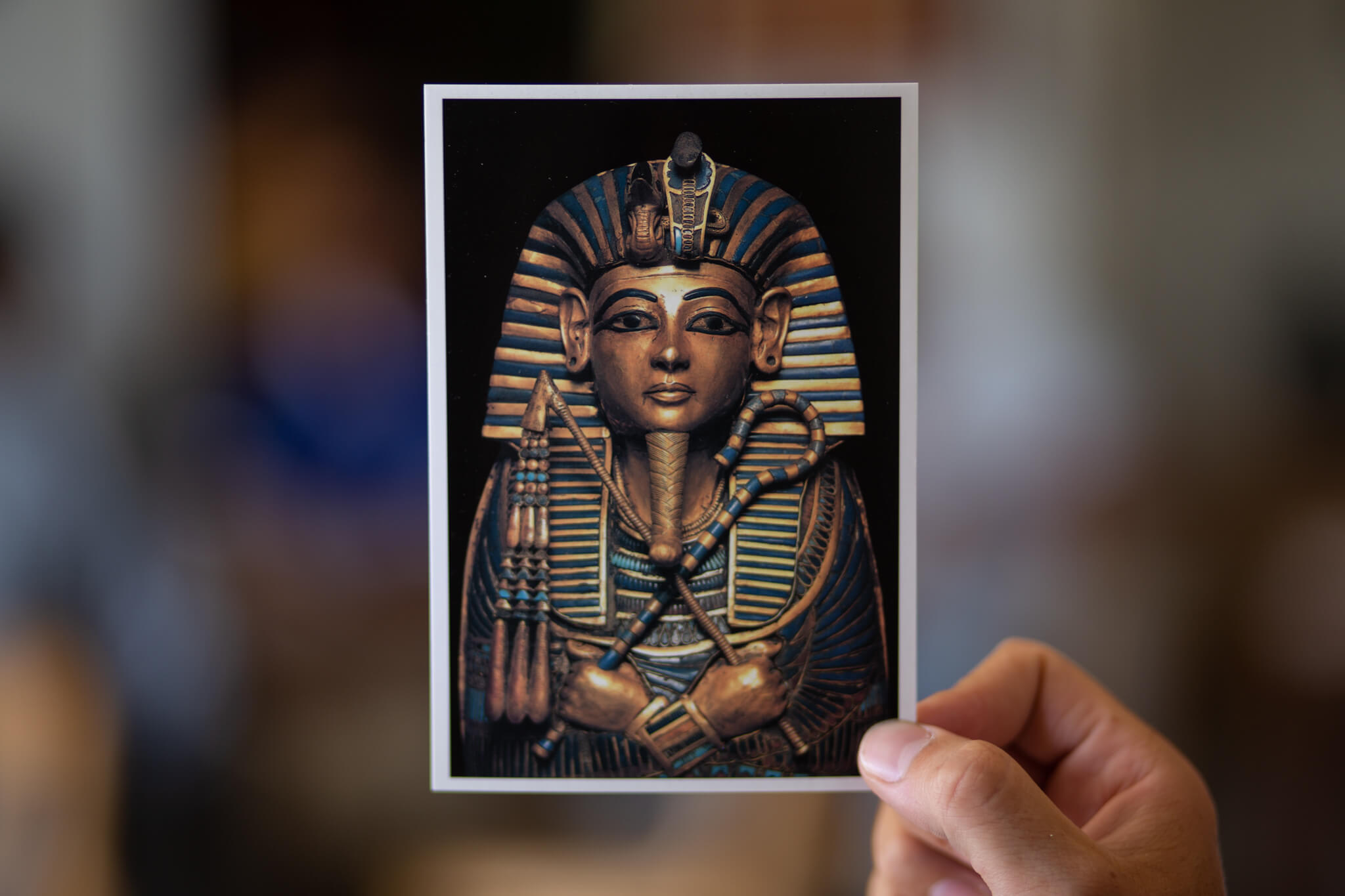

Tutankhamun’s funerary mask, discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1925.

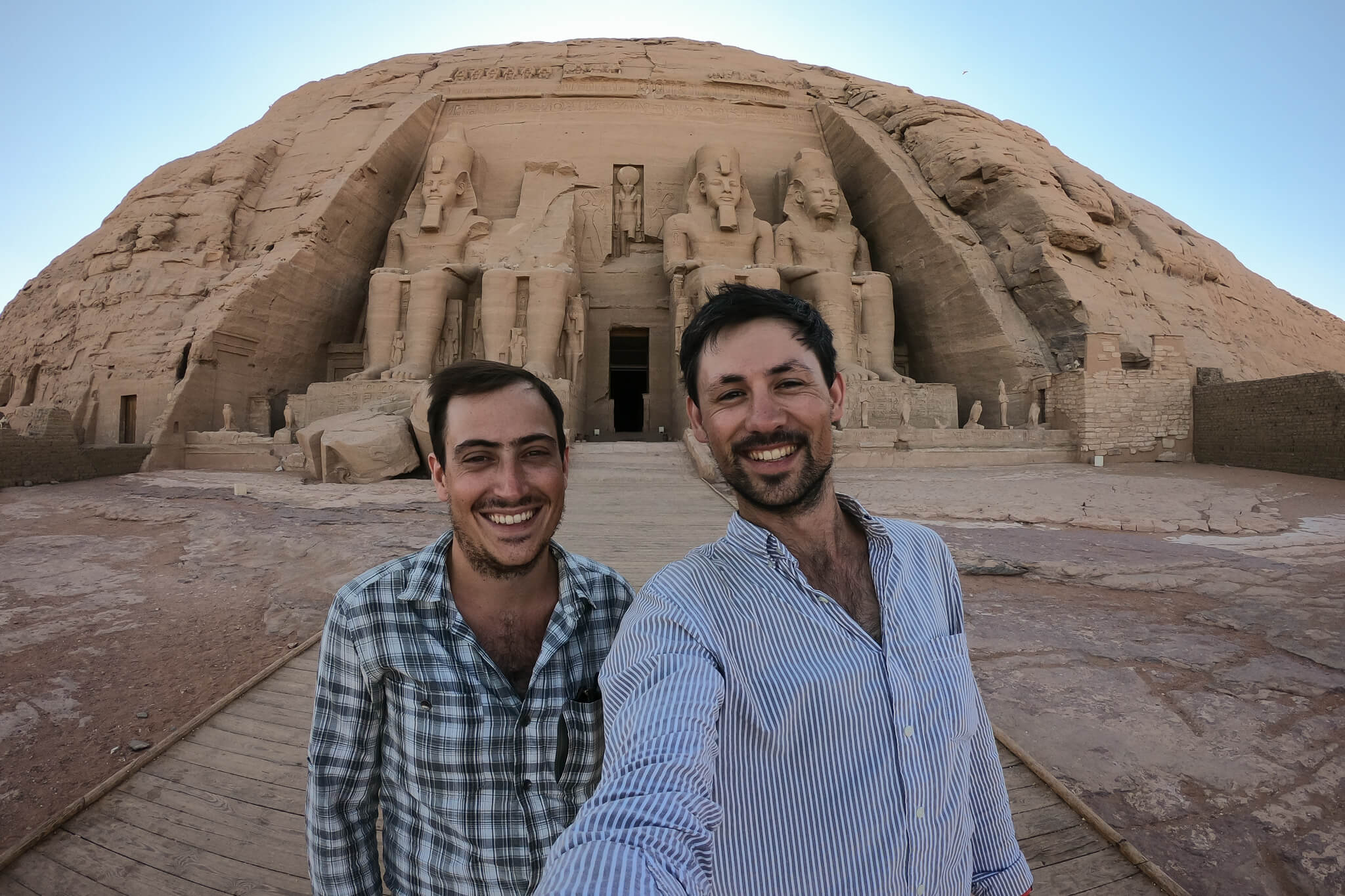

One of the positive effects of the absence of tourists is that we have the privilege of visiting Abu Simbel completely alone. Following the decision to build a hydraulic dam at Aswan, the waters of which would have threatened the sanctuary, the temple was completely dismantled and relocated under the aegis of UNESCO in 1968.

On the road, we take breaks every two hours in small shops in the shade for a drink. These are our refuges in the middle of the day, when the thermometer regularly climbs above 40°C.

In the afternoons, these areas are crowded with onlookers and workers.

With a 1300-kilometer border, the only crossing point between Egypt and Sudan is on Lake Nasser, via a ferry.

Once disembarked on the other side of the lake, the border post is in the middle of the desert.

Soon we will arrive in Sudan after 1000 kilometers on the road. What we don’t know at the time is that the border post is in disarray. It will take us more than 7 hours to cross.

– SUDAN –

From Wadi Halfa to Khartoum

Wadi Halfa is the first town on our arrival in Sudan from Egypt. Delayed by a laborious border crossing, we arrive at dusk in search of a small hotel to rest up.

This border town doesn’t offer much in the way of interest. Wadi Halfa is a town of passage.

It is bustling with trucks loading and unloading all kinds of household appliances from Egypt.

Sudan is far from being a tourist destination. Guesthouses and hotels are rare.

As we head deeper into the Sahara, the heat becomes more and more overwhelming. So, in order to ride when it’s not too hot, we set off in the morning at 5:30 am.

We set off again, but not without some trepidation. Unlike Egypt, which is teeming with towns and villages along the Nile, northern Sudan is a real cycling challenge. The country is completely deserted, and the only road to Khartoum is often dozens of kilometers away from the Nile. What’s more, the distance to the next “city” is 190 kilometers. To guarantee sufficient autonomy, we carried 2 batteries each for our bikes. Using the minimum assistance mode, we can cover just over a hundred kilometers with one battery. The road is good, but traffic is light. We pass a vehicle every 30 minutes or so.

At 45°C, pedaling feels like having a hairdryer on your face all the time. When we stop, the heat is reflected by the tar and burns our calves. It’s so hot that our perspiration evaporates instantly, leaving our skin covered in salt. Fortunately, we sometimes find small shelters on the side of the road where large jars filled with water rest. These are used by road users for ablutions and refreshment.

After 170 kilometers under a leaden sky and despite drinking 10 liters of water, the cramps got to me and I collapsed in the shade under a small shelter.

Finally, after a short break, we reach the village of Abri on the banks of the Nile. A source of life, we’re happy to be back.

We take up residence in the only guesthouse for hundreds of kilometers.

The bikes are holding up well. The temperature doesn’t affect the batteries, and loaded as we are, the electric assistance is a great relief when it’s windy or there are slight hills.

Around the village of Delgo, we choose to explore an island on the Nile.

To do this, we have to cross the river on a motorboat.

We’re not the only ones who want to make the crossing. Without a bridge, it’s the only way to get from one village to another.

We gaze at the Nile, trying to imagine that the water before our eyes has its source thousands of kilometers away. It’s a soothing moment at dusk, when the heat drops.

We wake up to a windstorm and sandstorm, as can happen in the Sahara.

Traffic in Sudan is so light that travelers can wait several hours before seeing a truck or car.

Running late because of the sandstorm, we decide to take a mini-bus for part of the route. Continuing by bike would mean missing out on the archaeological wonders of Sudan.

We arrive in Karima, in the heart of the Sahara. The heat is stifling, sand and dust invade everything. Shoes, roads, houses… making life in these parts very difficult.

We stock up in small stores like this one.

Or in markets, like this one in Atbara.

- Sudan is a country that lacks everything except smiles and joie de vivre.

We pass through an incredible animal market in Kabushiya.

Heavy rains hit the region, causing flooding. These rains herald the end of the Sahara and the beginning of the Sahel.

According to some religious texts, the Prophet Mohammed dyed his beard with henna. Some men dye their beards in the hope of gaining blessings.

In the afternoon, during the hottest part of the day, we take refuge in small restaurants.

Under the amused gaze of the children.

The breathtaking site of Meroe. It was these forgotten pyramids that first drew me to Sudan. This country has more pyramids than Egypt. They are also funerary tombs, erected in honor of the kings and queens of Nubia. They are, however, smaller and more pointed than their Egyptian neighbors.

We wander alone between the ruins and tombs of the Meroe site.

The site is extensive and excavations are far from complete. Many remains have yet to be discovered.

- Despite the heat and the sand, our bikes held up!

- Every Friday evening in Omdourman, a Sufi ceremony is held, a branch of Islam characterized by dancing rites. The ceremony begins with the participants crossing a cemetery to the sound of drums and chants.

Some are dressed in green, the color of Islam, from head to toe.

The community prays, sings and dances with impressive fervor.

Participants spin or sway back and forth while repeating the “shahada” (the Muslim profession of faith) in the expectation of making contact with Allah.

Some of them go into a trance and no longer seem to control their own movements.

- Bodies move to the sound of the drums throughout this ritual, which lasts almost two hours.

This month’s journey across the Sahara by electric bike was more demanding than we had imagined. The heat, wind and dust surprised us with their intensity, and humbled us for these desert peoples. We won’t forget the big smiles and welcomes that accompanied us along the Nile.

On the other hand, the Easybike brand’s reception of our adventure was unfortunately less warm. Although we were able to use their bikes, they failed to meet their financial commitments for the production of the documentary and the follow-up to this operation.

See the interactive map of our adventure on LiveXplorer.