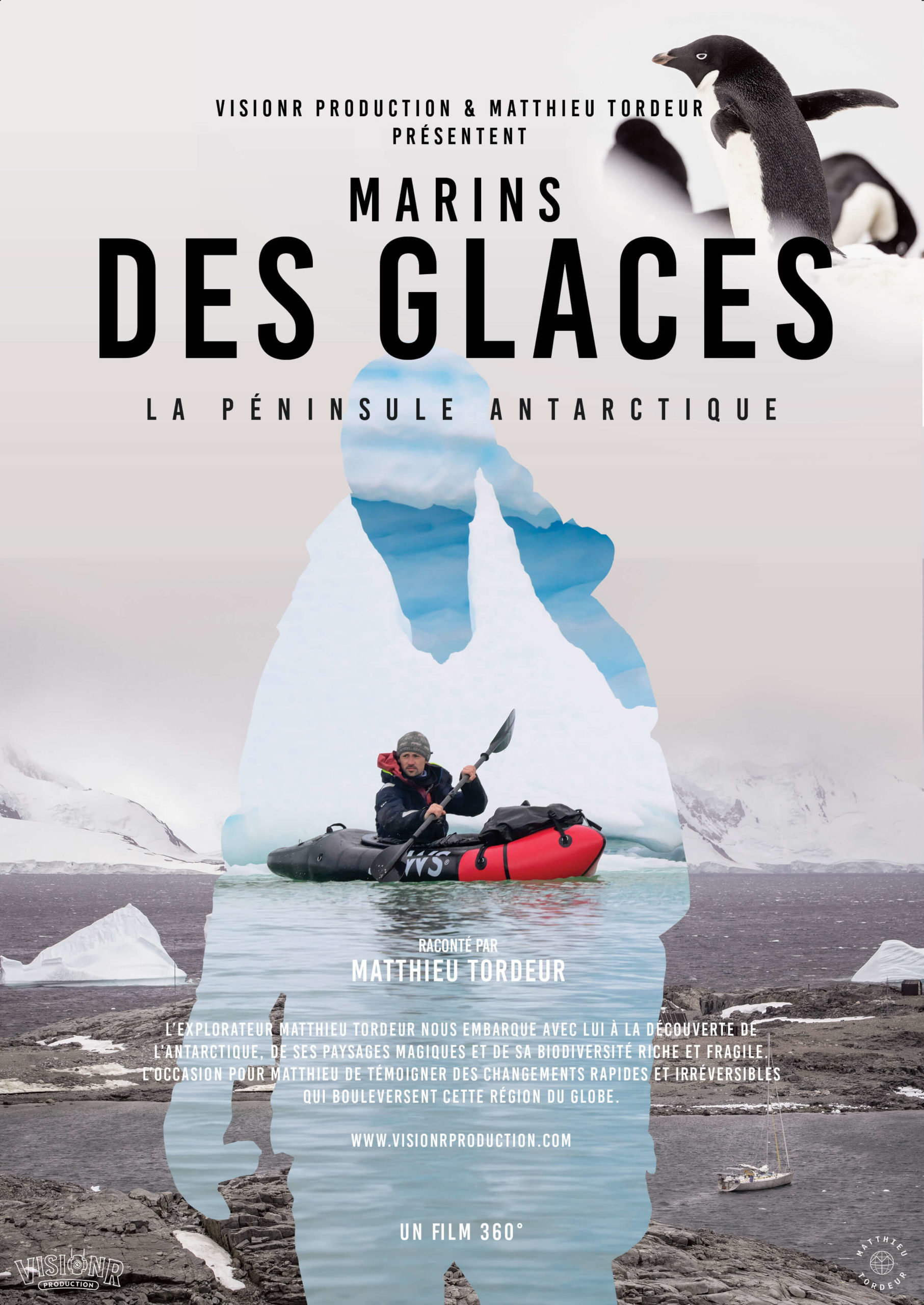

SAILING THE ANTARCTIC PENINSULA

Two months’ sailing to Marguerite Bay

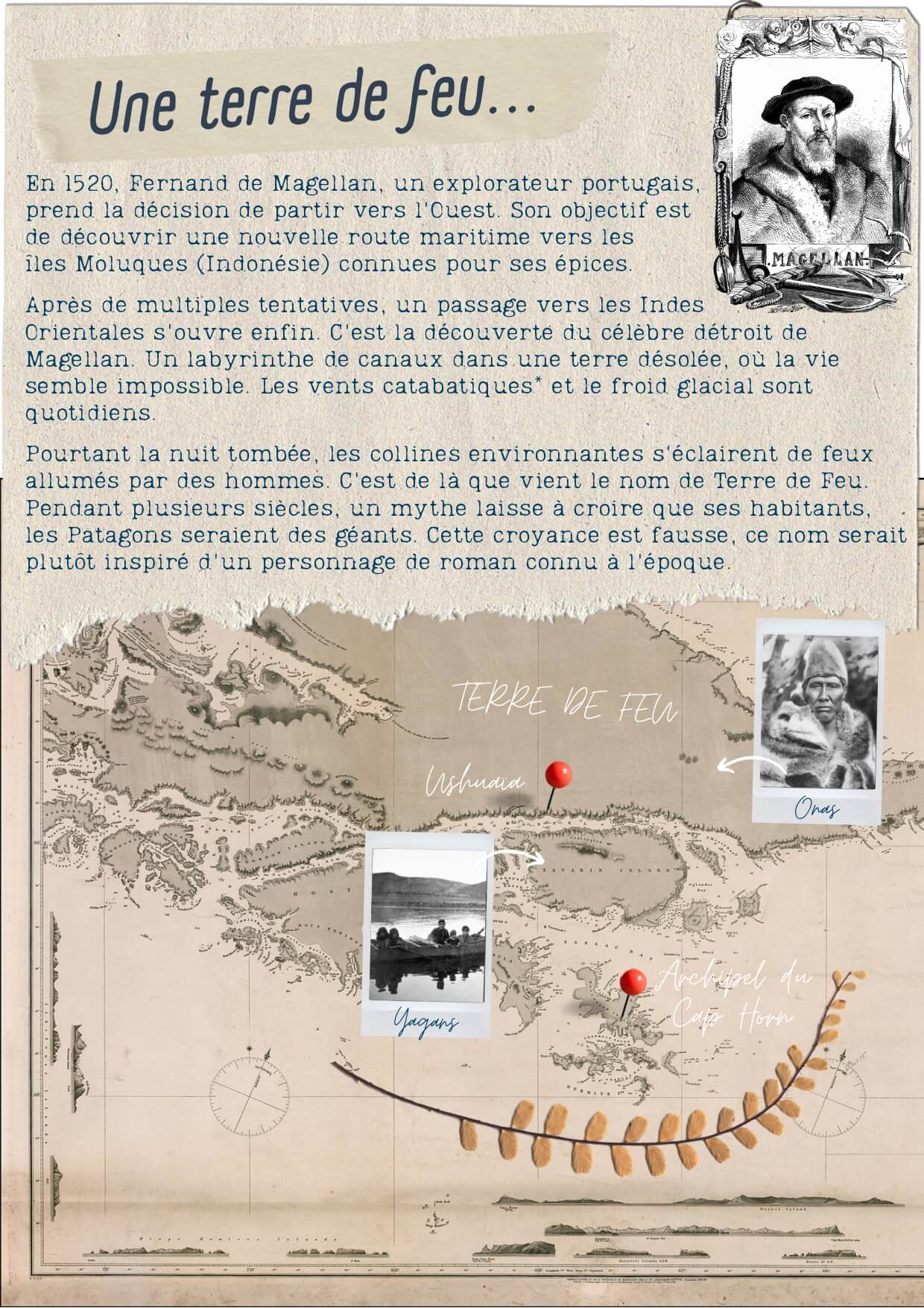

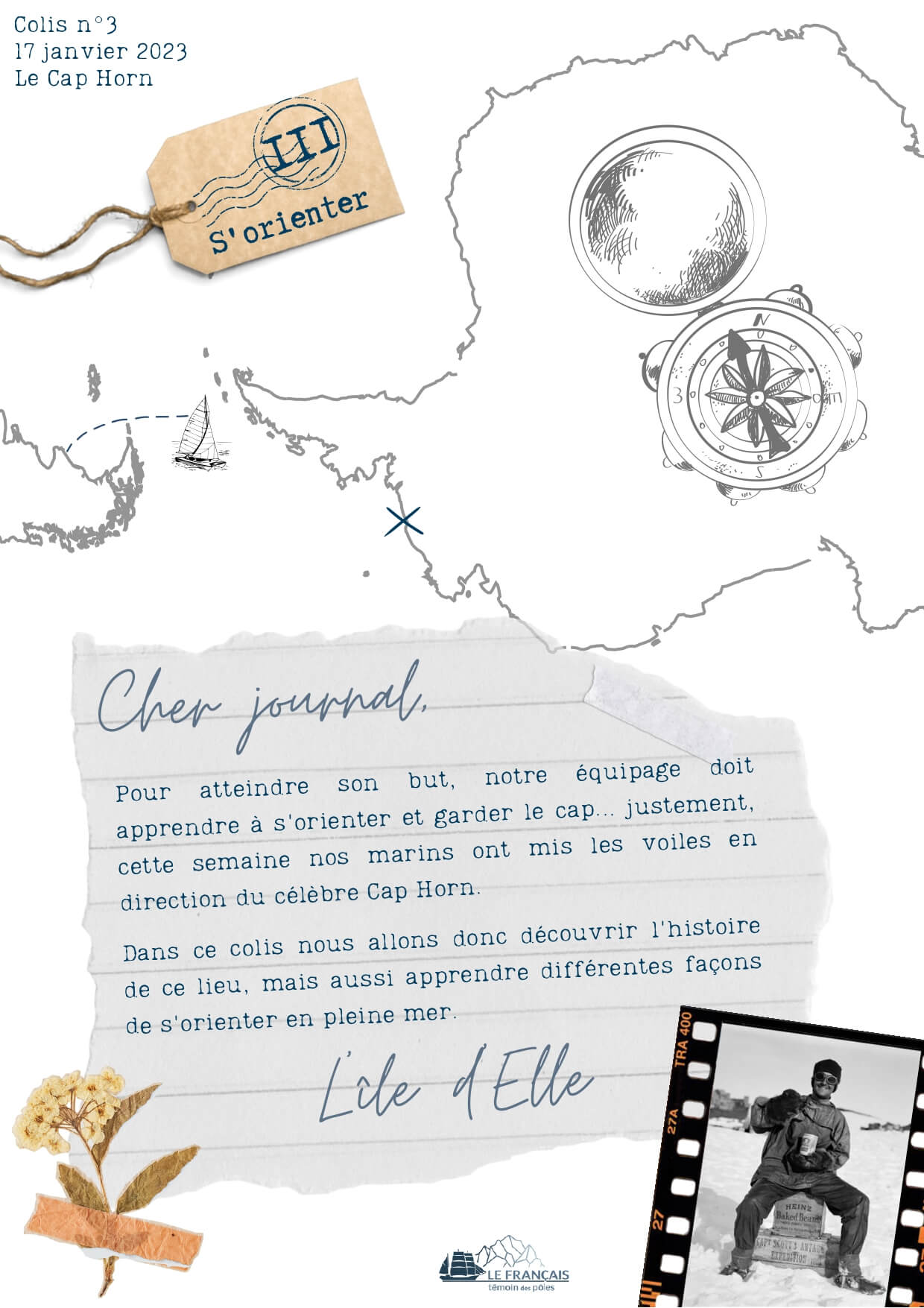

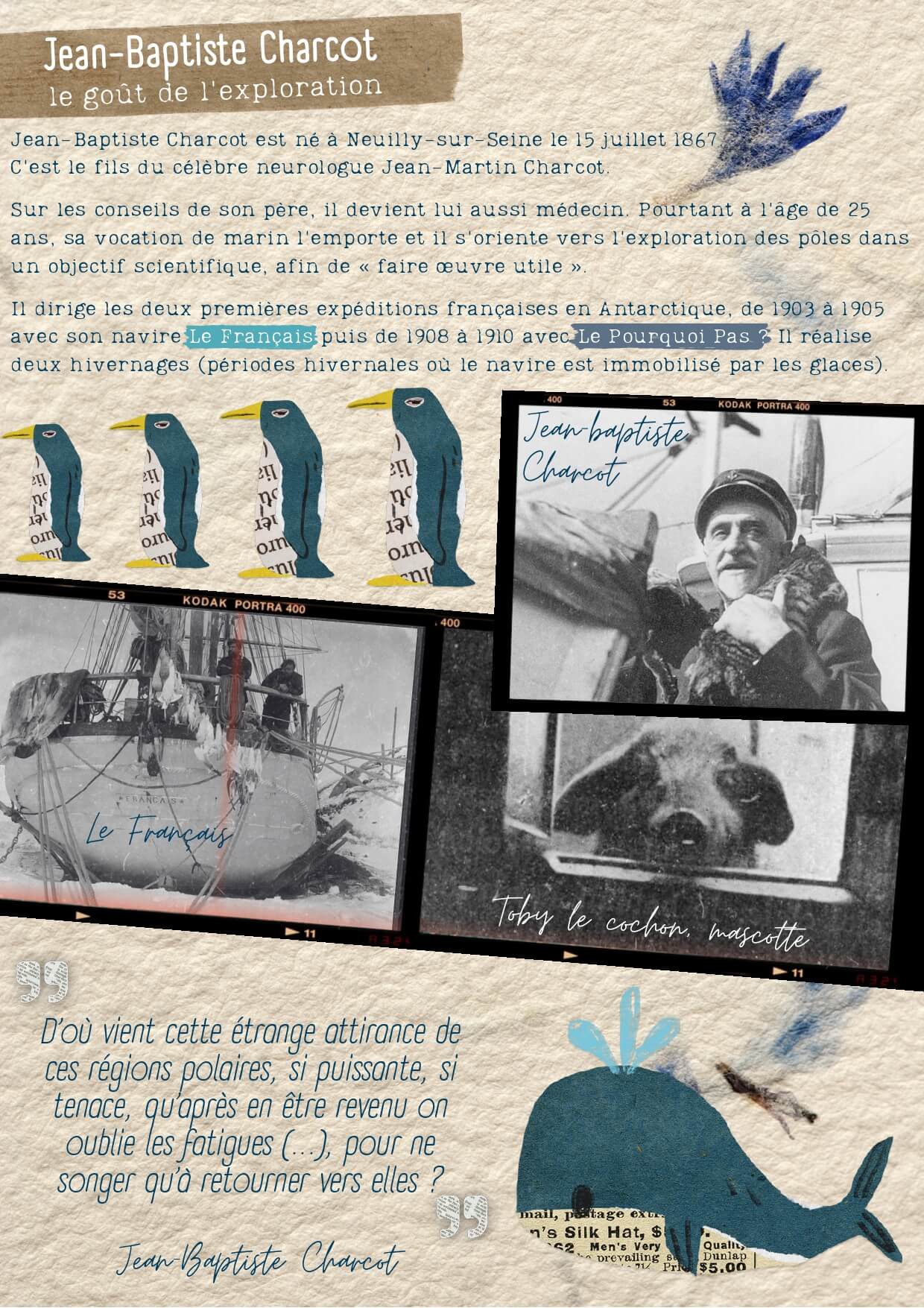

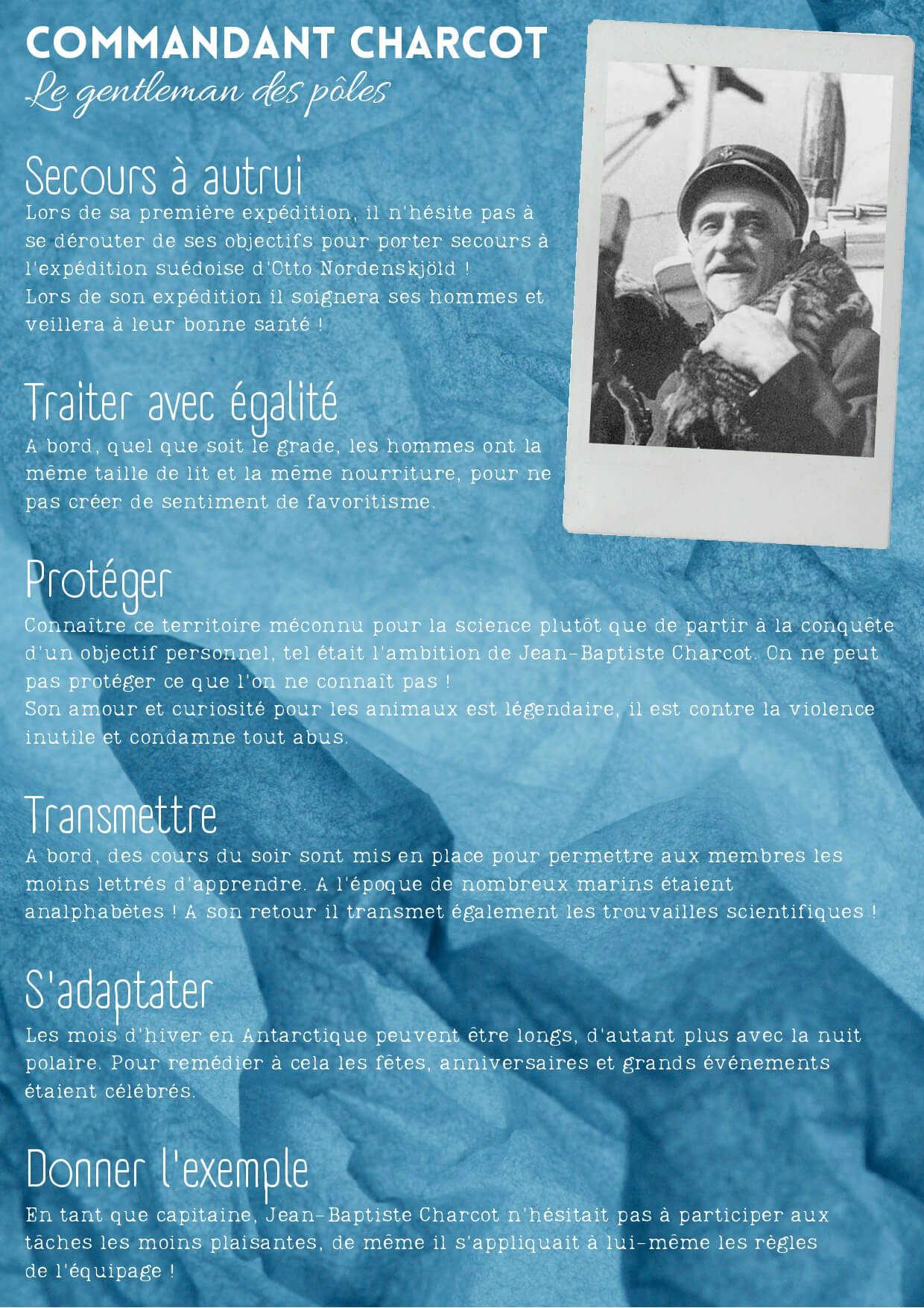

In January 2023, I’ll be embarking on L’Île d’Elle, a 16-metre sailing boat, for a long-haul discovery of the Antarctic Peninsula. Our goal is to sail down to Baie Marguerite, for 2 months. Named by polar explorer Jean-Baptiste Charcot in homage to his wife Marguerite, this immense indentation in the middle of the ice is difficult to access, and very rarely reached by sailing boats.

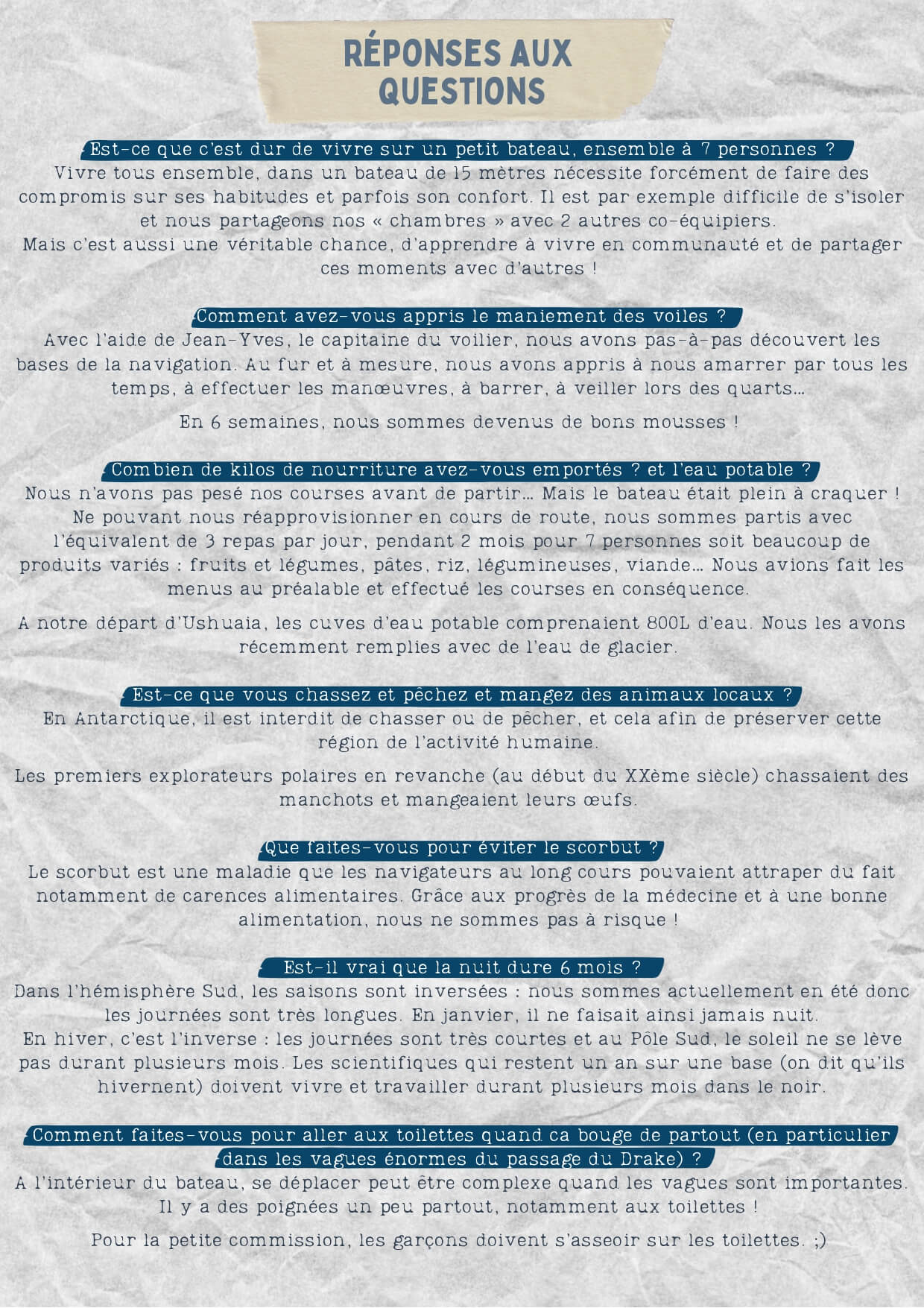

With the Endowment Fund Le Français, a witness to poles (now Témoins Polaires), of which I am one of the trustees, we have set up a school partnership to share the beauty, richness and fragility of this remote region with youngsters.

Equipped with cameras, binoculars and hydrophones, we’ll be sharing the magic of these southern lands in real time, through immersive content. Each week, we’ll provide schoolchildren with educational content on biodiversity, ice, climate, the environment…

Raising awareness and popularizing science to preserve the poles

This partnership, straight from the ice, was free and open to all schoolchildren from CE2 to CM2. Over 16,500 students in 28 countries took part!

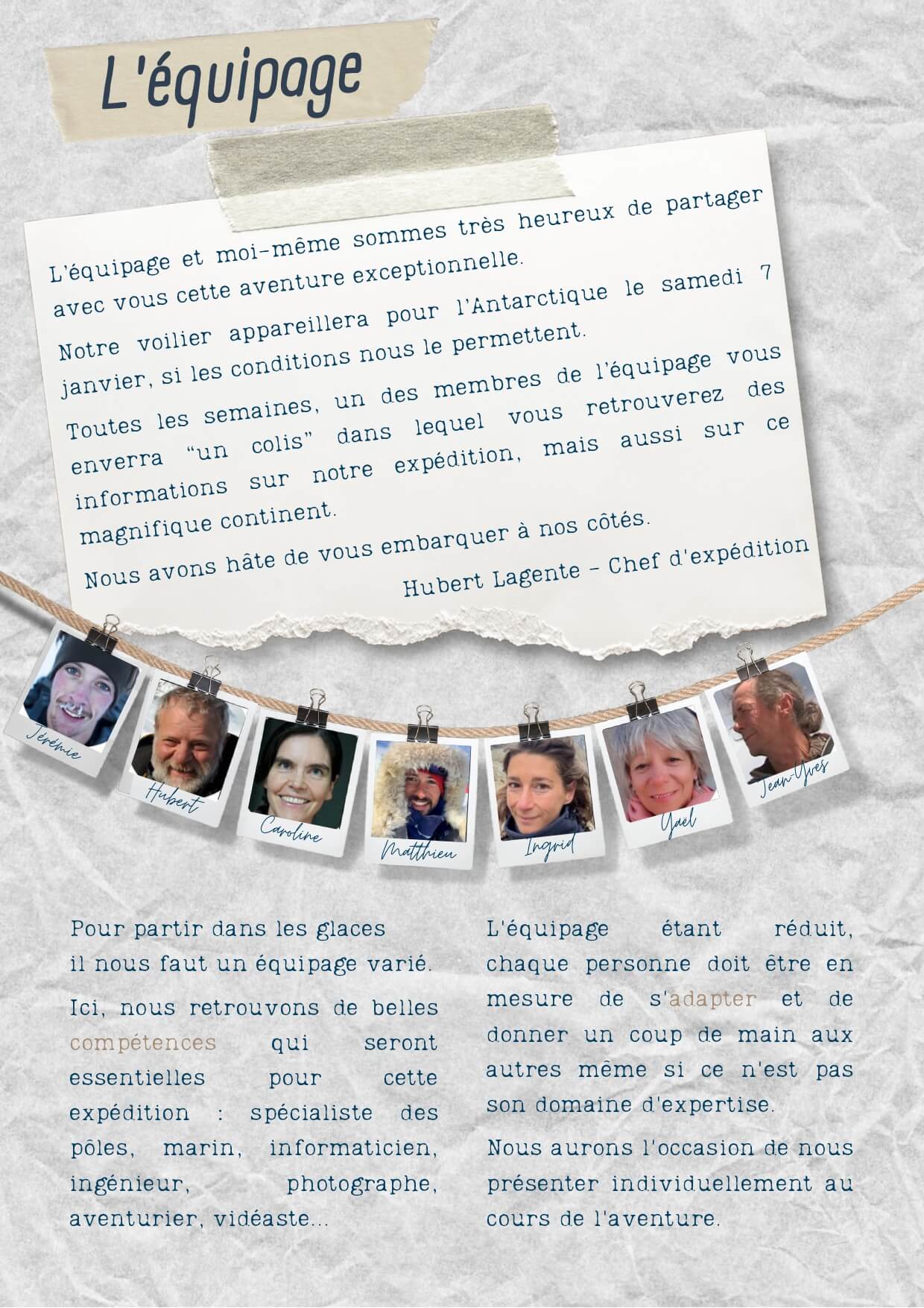

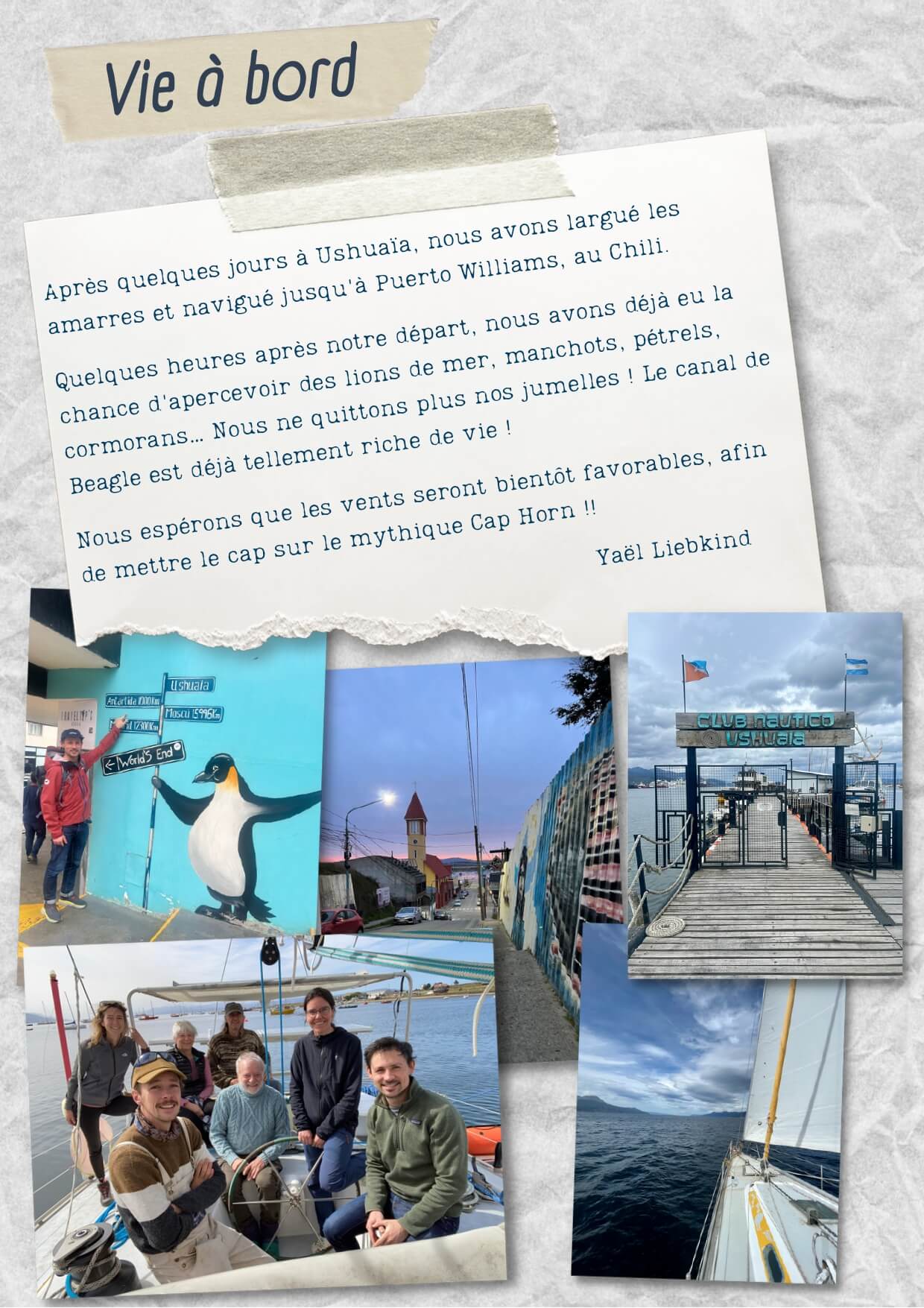

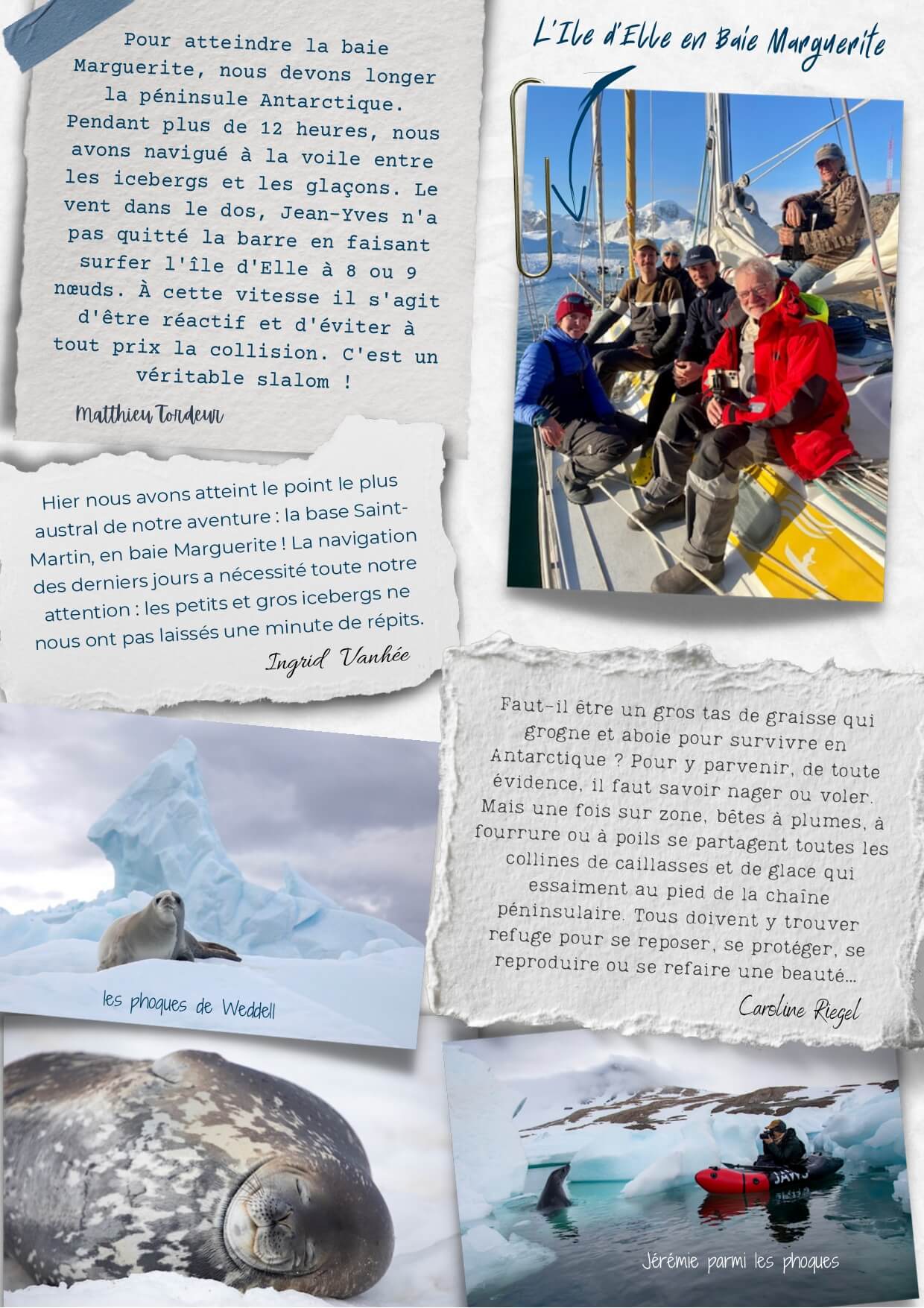

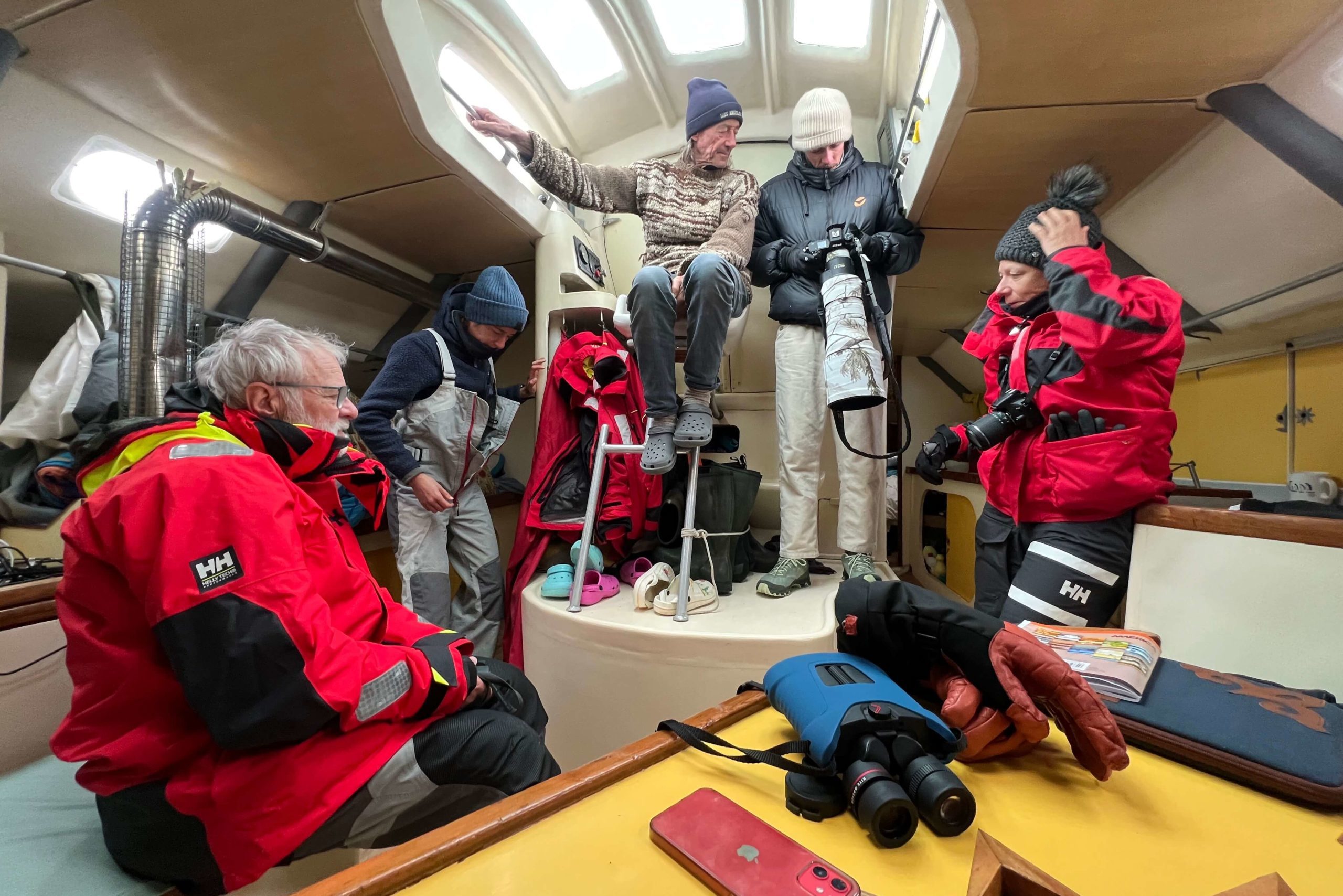

At the beginning of January, the crew meets up at the Club Nautico d’Ushuaïa. L’Île d’Elle, a 16-meter sailboat, is waiting for us at the dock. Her warm yellow colors are reminiscent of the sun and the tropics. And with good reason: Jean-Yves, our skipper, brought the boat all the way from Polynesia. He built what he calls his “floating home” with his own hands in 2006. He wanted his boat to be fast enough to sail the world’s oceans, tough enough with an aluminum hull to cope with ice and friendliness. Its shallow draught allows it to squeeze into small creeks, which comes in handy in Antarctica when bad weather arrives. Fitted out with mooring lines, solar panels and canisters, this is a true expedition vessel, capable of accommodating up to nine people.

This time there are seven of us. From left to right: Ingrid Vanhée, biodiversity specialist and wildlife investigator; Jérémie Villet, multi-award-winning wildlife photographer; and Yaël Liebkind, a Swiss Antarctic enthusiast by night and social activist by day. Jean-Yves Lepage, the boat’s skipper, a long-distance sailor and sailboat builder, Hubert Lagente, a former winterer at the Dumont d’Urville scientific base in Terre Adélie, and Caroline Riegel, an avid traveler and documentary filmmaker. An eclectic crew ranging in age from 30 to 74, but all united by the same passion for the poles.

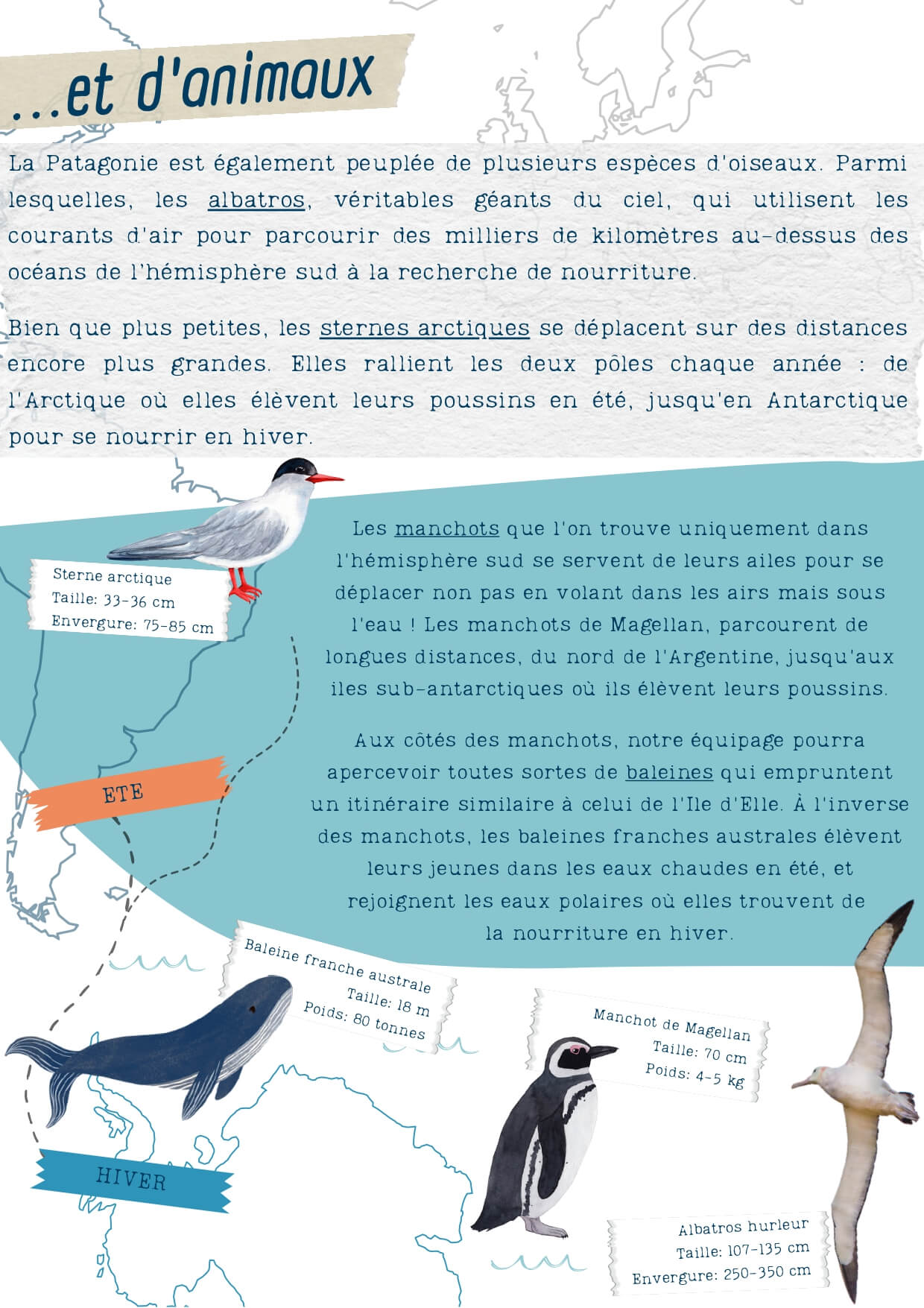

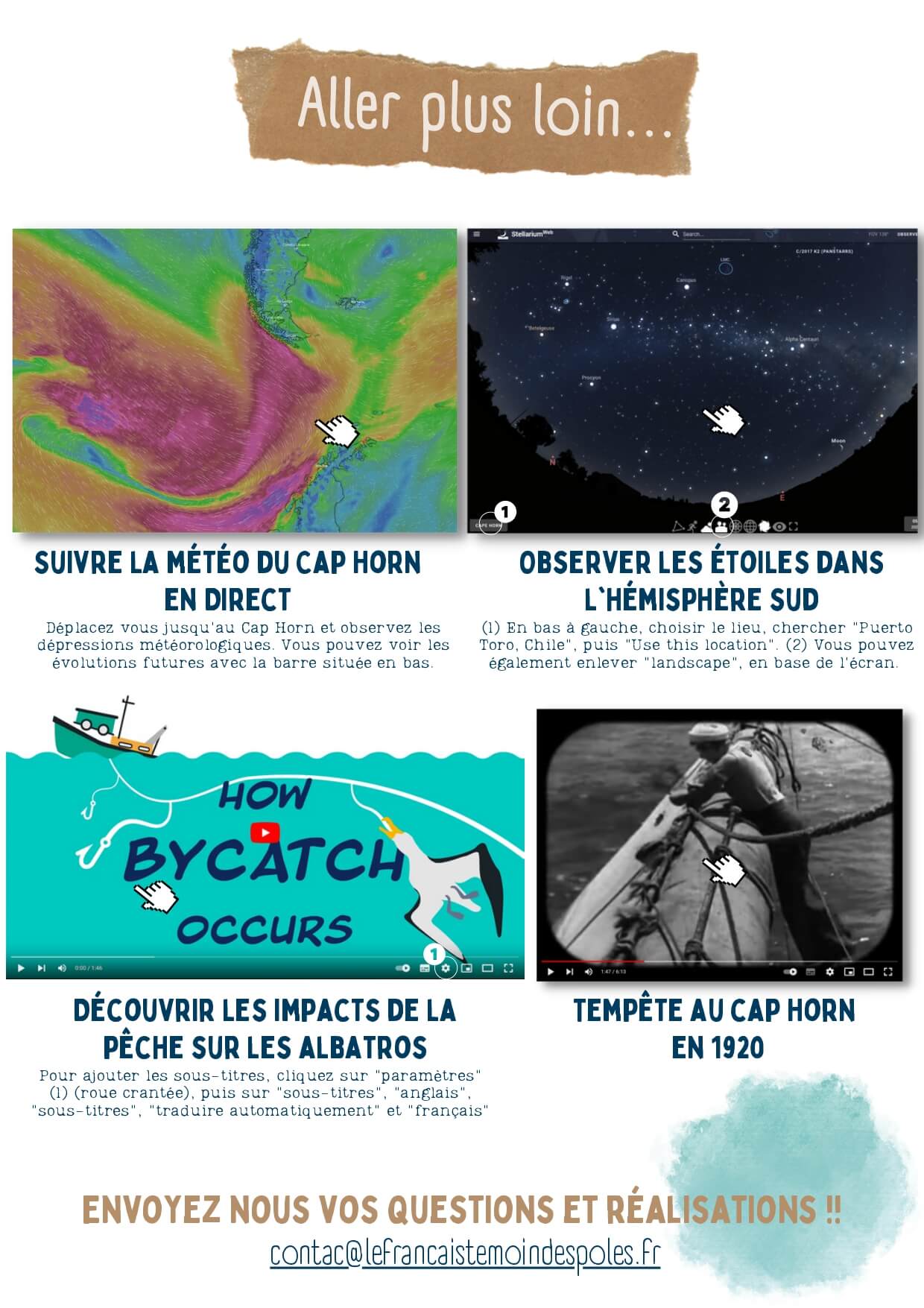

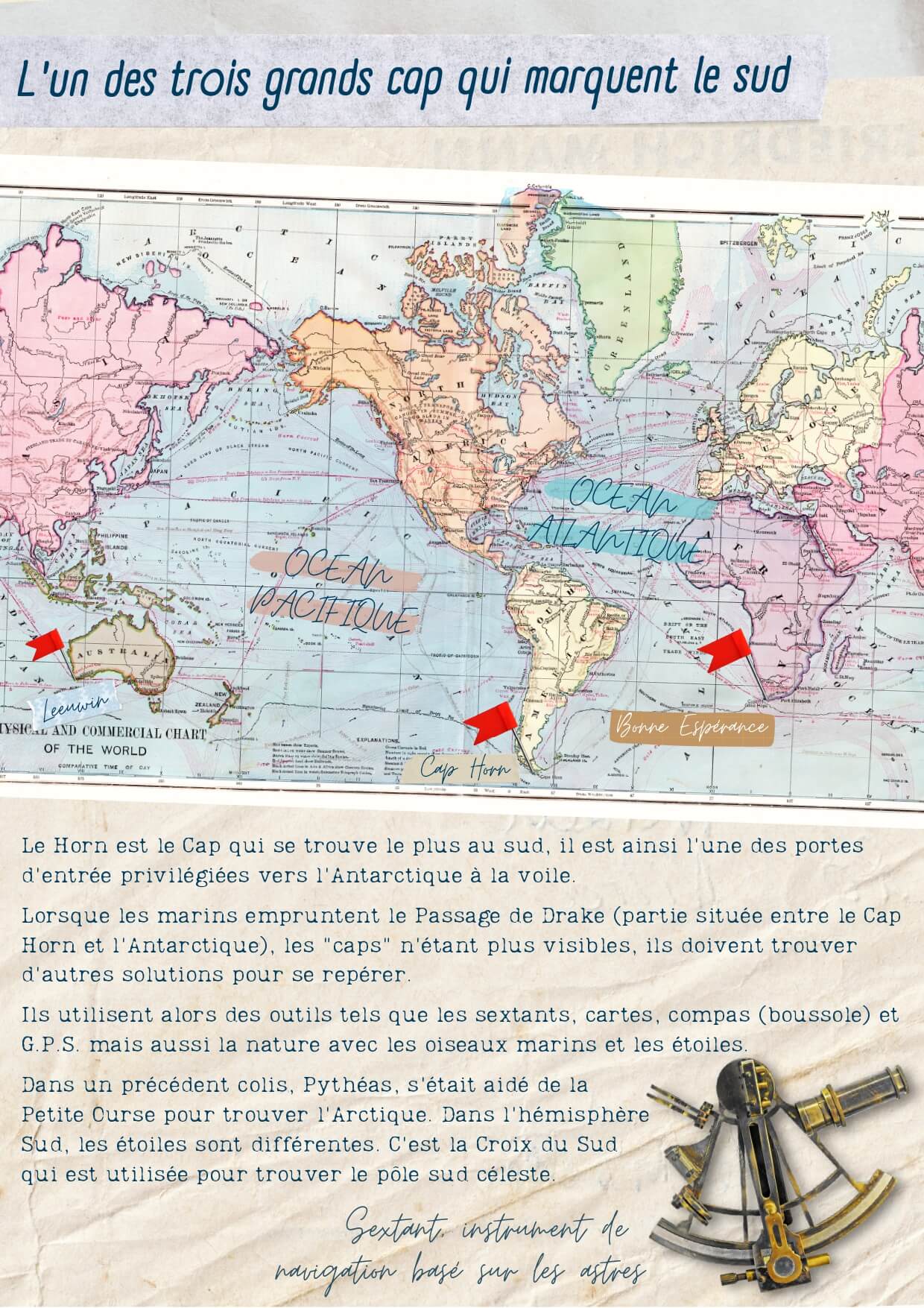

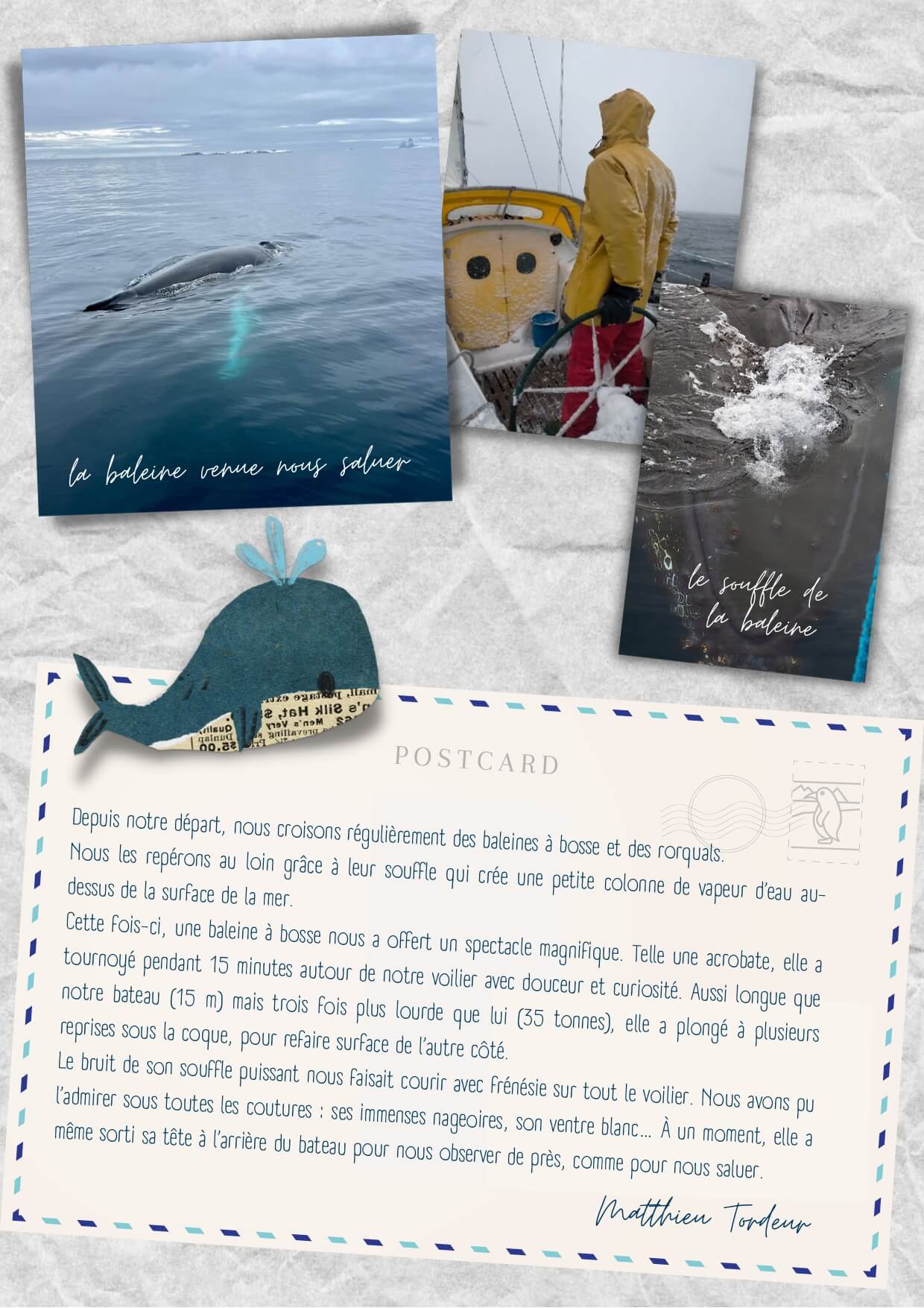

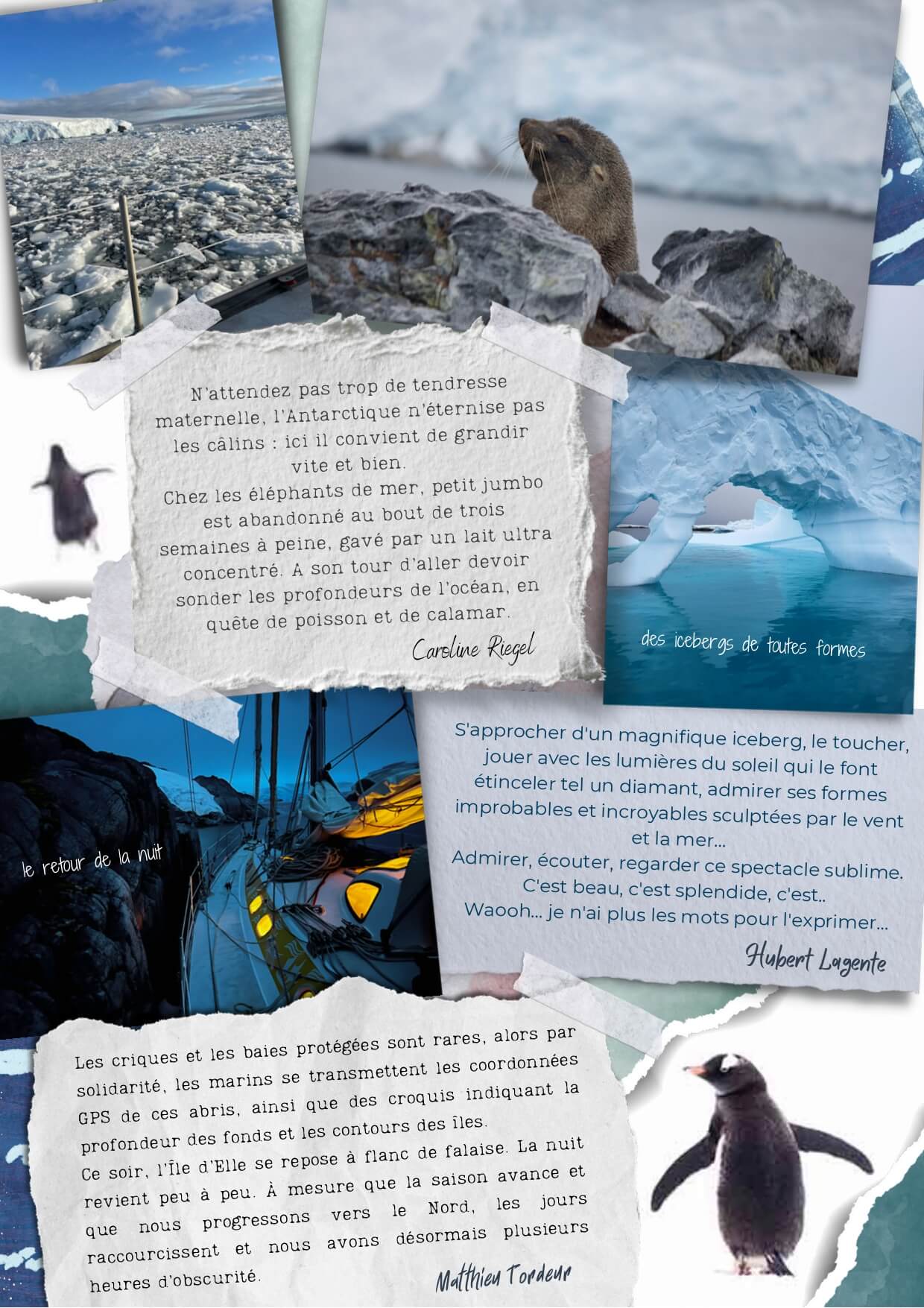

After provisioning the boat and a final video-conference with our partner classes, we set sail on January 7, at the first opportunity, to pass through the mythical Drake Passage to Antarctica. This strait must be approached with great humility: it is the meeting point of the world’s two largest oceans, where enemy masses of water and air clash. Four days at sea and a few gulps later, we enter another universe. On deck, we’re stunned by the spectacle before us. Under a zinc-colored sky laden with threatening clouds, filtered light illuminates drifting icebergs. They take on the ephemeral shapes of towers, arenas, fortresses, buildings… Pierced by the sun’s rays, the ice refracts a turquoise color and the submerged part of the icebergs gives the water a turquoise-blue appearance.

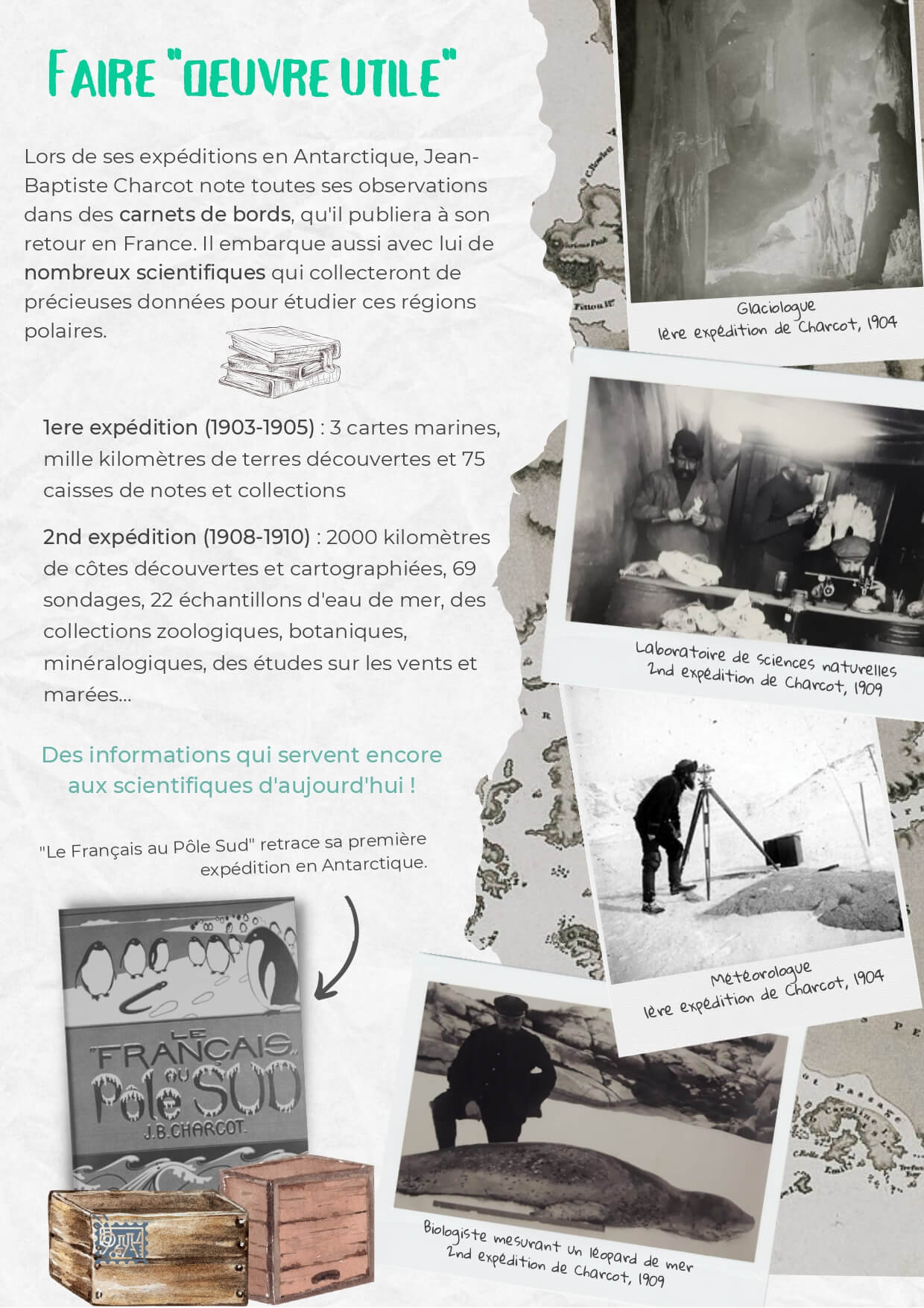

Commandant Charcot liked to say that his expeditions were intended to do “useful work”. That’s what I’d like to do with mine, in my own modest way. For this sailing adventure, I’m piloting an awareness-raising project on behalf of the Polar Witnesses Endowment Fund, with the idea of raising awareness and respect for the poles, symbols of the beauty and fragility of our planet. On board, we’ll be creating content to share our observations with youngsters. Equipped with cameras, binoculars and hydrophones, we’ll be transmitting educational content on biodiversity, ice, climate and the environment to schoolchildren every week. Interactive documents will be sent to teachers along the way. We’ll also be regularly answering questions from our budding adventurers by satellite phone. In all, over 16,500 primary school children in 28 countries will be following our expedition.

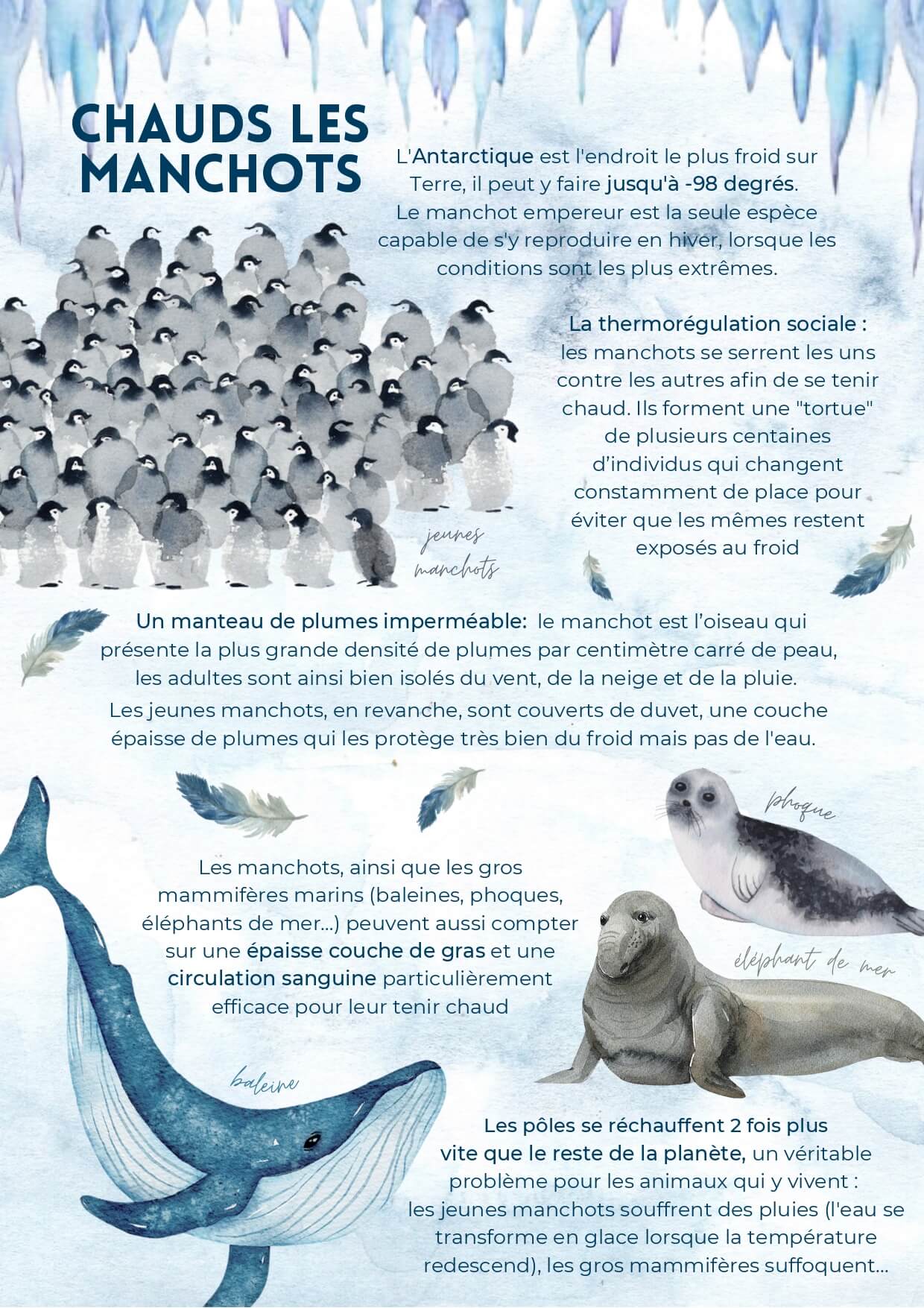

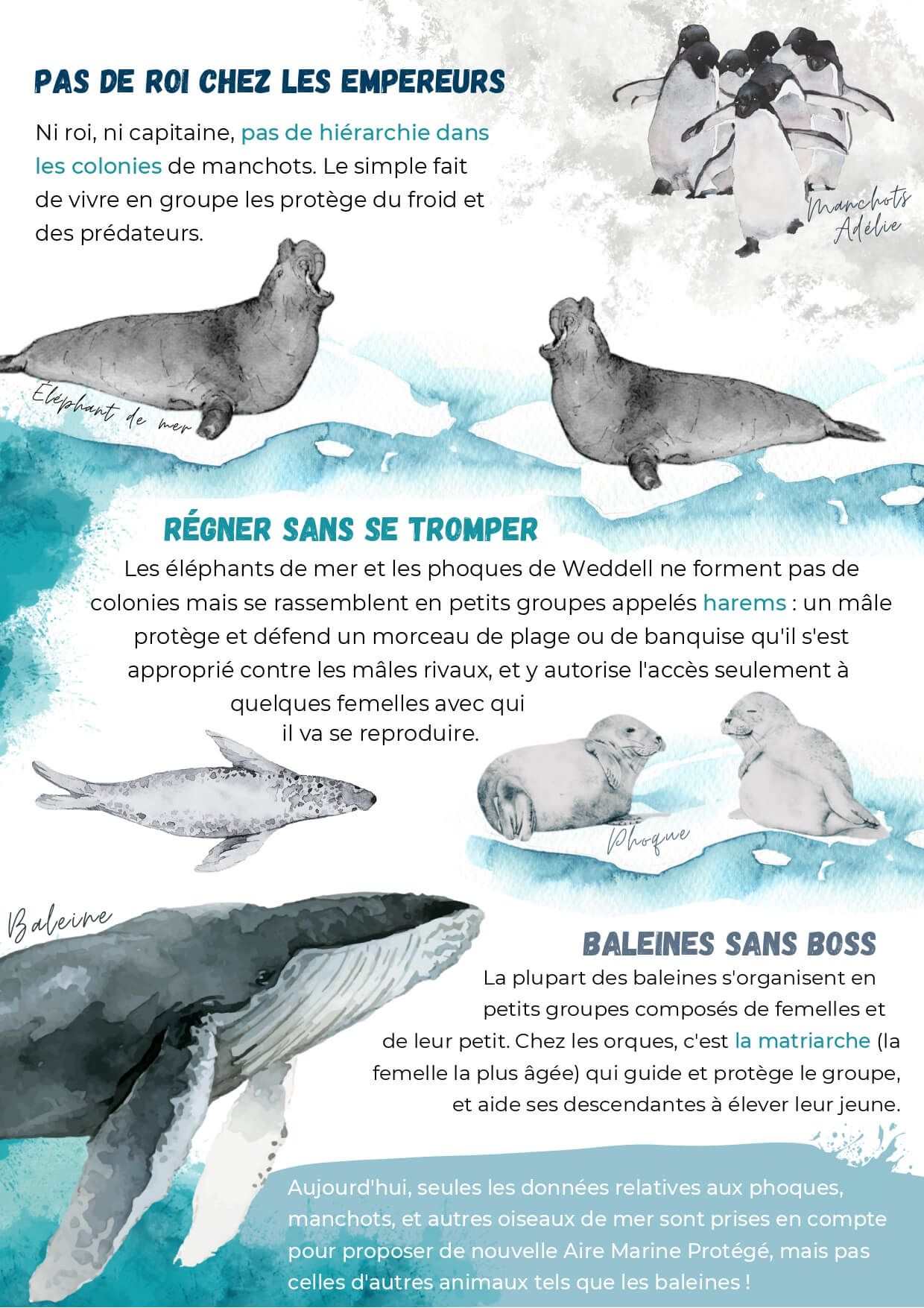

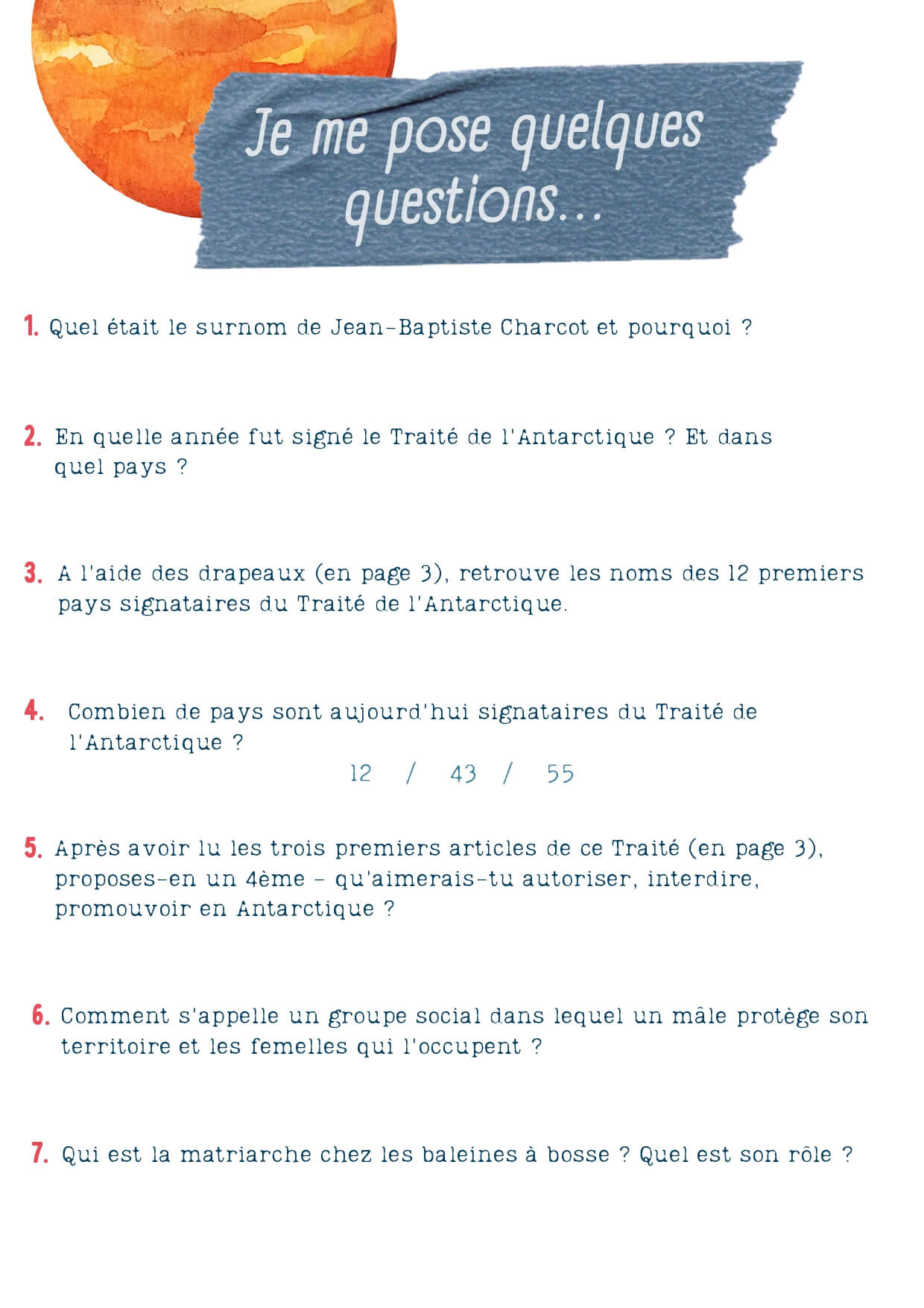

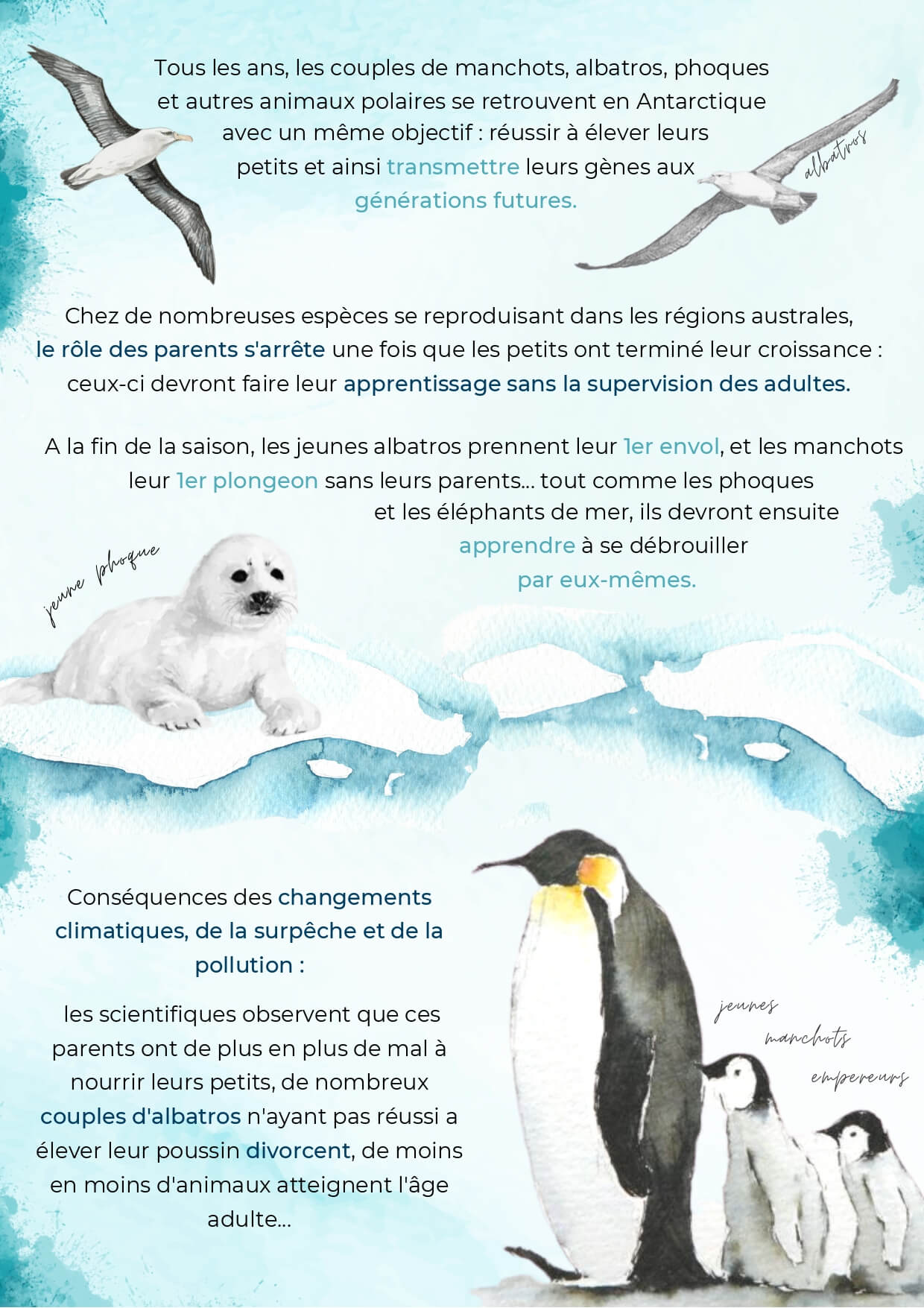

Our journey takes us along the west coast of the peninsula, past the Brabant, Antwerp, Renaud and Lavoisier islands, then on to the immense Adelaide Island, 4,600 square kilometers of ice and snow-capped mountains, with its first-morning-in-the-world feel. Antarctica may be a desert, but it’s a very inhabited desert. Life is literally everywhere. Here, a Weddell seal emerges from a patch of ice, gliding through the water in front of our bow. Further on, a ballet of terns twirls above the mast. Then a colony of penguins, busy raising their offspring, the male and female taking turns incubating the egg and building the nest, as if in a race against time for the survival of their species.

Of all these encounters, one in particular stands out for me. As we anchored off Horseshoe Island, I decided to launch my packraft (a small inflatable boat). As I was sailing alone between the icebergs, a big black head popped out in front of me. A leopard seal! Bigger than a seal and weighing up to 400 kilos, it’s recognizable by its reptilian head and elongated neck. It is one of Antarctica’s most ferocious predators. To feed, it prowls around penguins, grabbing them and tearing them apart with its teeth. For about ten minutes, he circles me without taking his eyes off me, surfacing every 30 seconds. I know I’m at the mercy of his curiosity. But he’s not threatening me, he’s testing me. He sniffs me, looks at me. A fang in the packraft, and I could be in the water. For a brief moment, I have the strange sensation of becoming prey. A feeling of vulnerability that puts you in your rightful place and reminds you that this is no place for man.

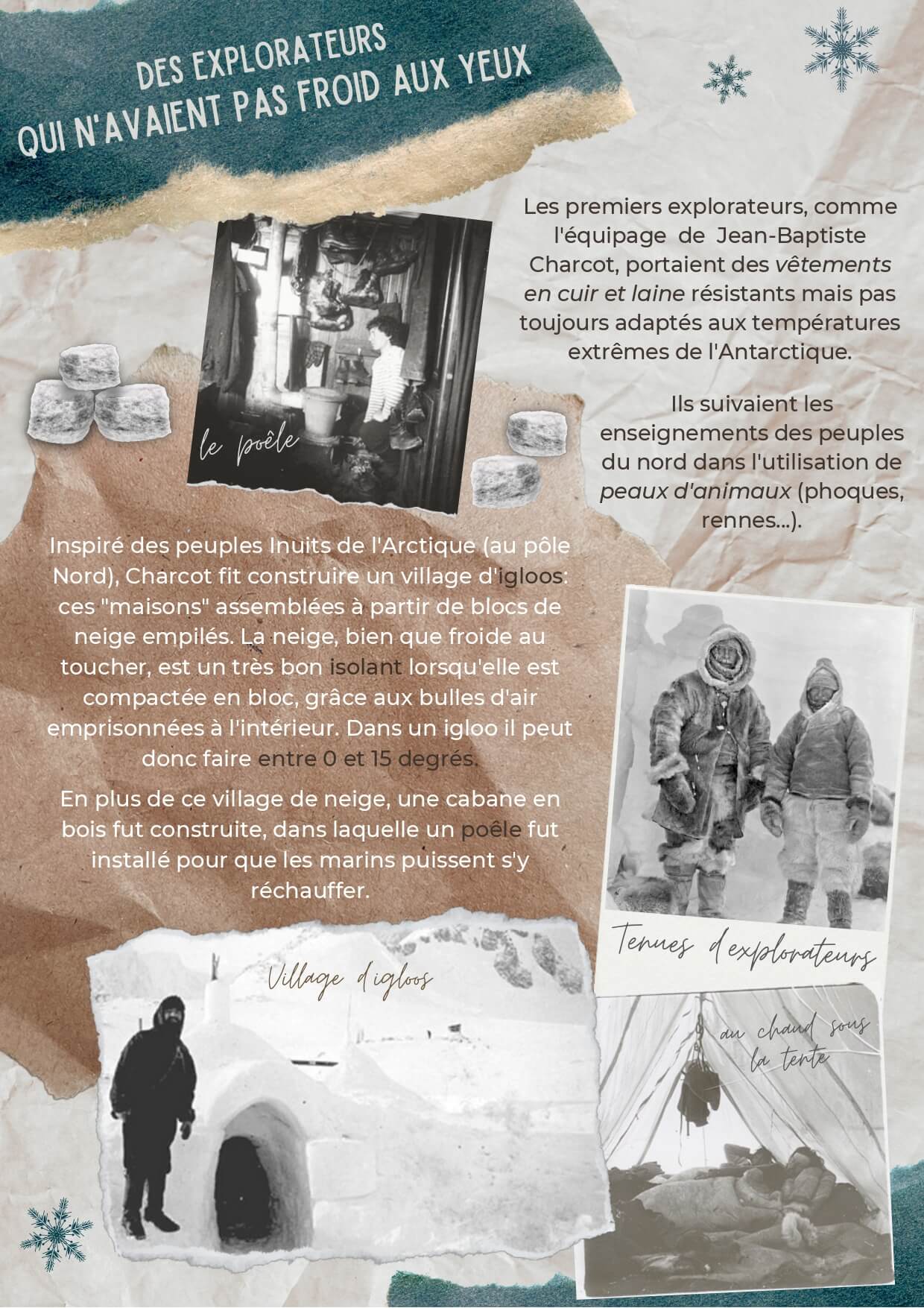

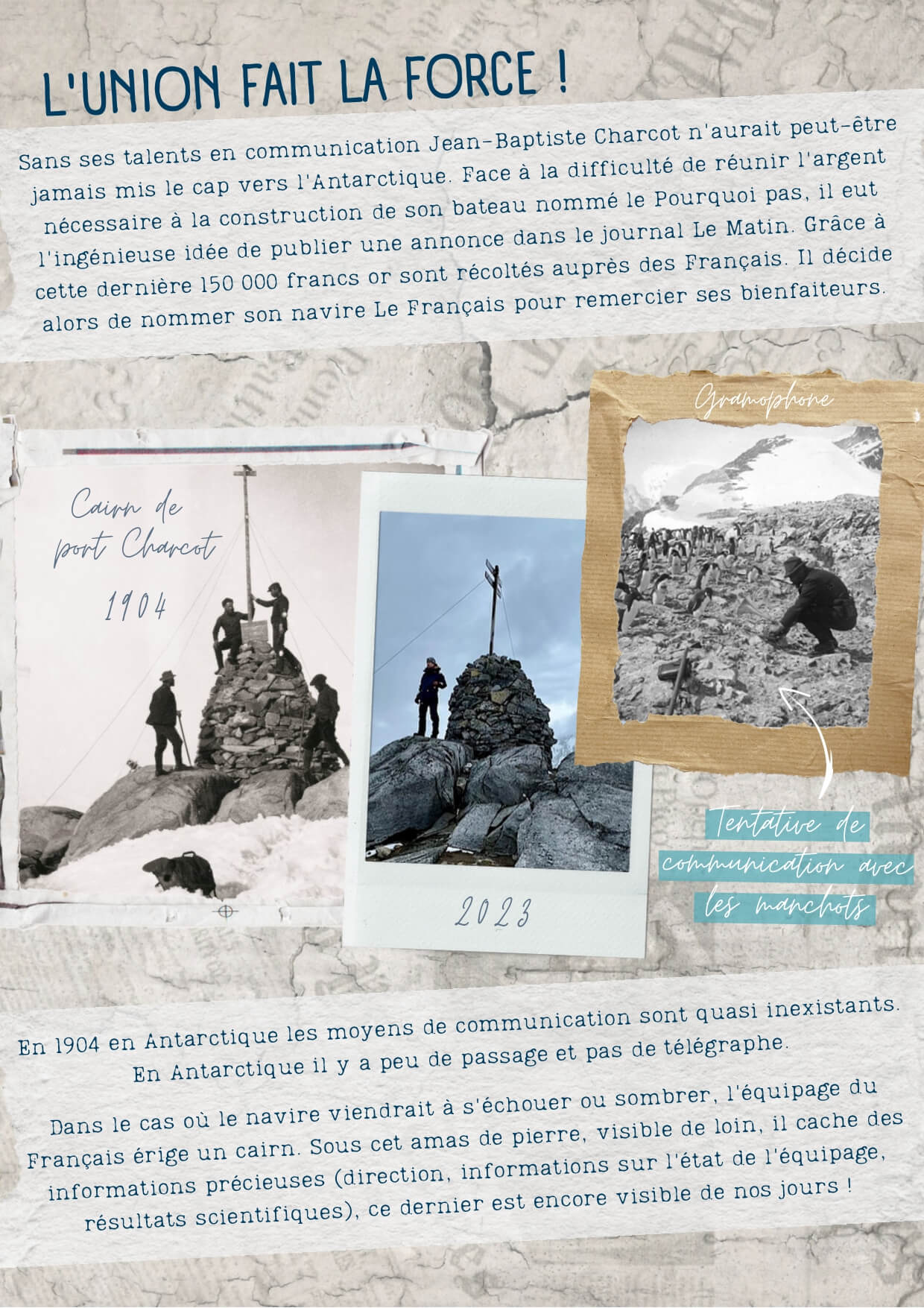

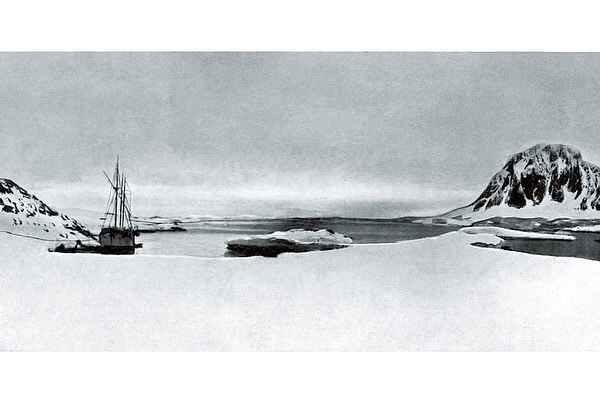

It’s with a touch of emotion that we moor our sailboat L’Île d’Elle, at the exact spot where 119 years earlier, the ship Le Français of the famous polar explorer Jean-Baptiste Charcot stood. From March to December 1904, Charcot wintered in a bay north of Booth Island in the Wilhelm Archipelago. Some twenty men studied currents and tides, astronomy, terrestrial magnetism, geology, botany and zoology… An “F”, like

After a stopover on Petermann Island, where Jean-Baptiste Charcot wintered for the second time in 1909, we head for the Ukrainian scientific base Akademik Vernadsky, where 14 people are engaged in long-term studies of meteorology, seismology and biology. We are warmly welcomed by the team of scientists, who explain that the station wasn’t always Ukrainian. It used to belong to the United Kingdom and was known as the Faraday Station. It was ceded to Ukraine in 1996 for a symbolic £1. One of the special features of this station is that it has a bar! At the time, the station’s architect was asked to build a meeting room. He decided that a bar would be more appropriate. So he built a pub from scratch, complete with pool table, darts board and high stools, just like you’d find in England. He was fired, but his work lives on!

Sailing on the Antarctic Peninsula requires a real understanding of the sea, weather and ice. There are no harbors or sea rescue services here. To last in the Southern Ocean, you have to find small protected bays and coves to rest in and protect yourself from the elements, which can be fierce and unpredictable. As a gesture of solidarity, the few sailors pass on to each other the GPS coordinates of these shelters, as well as sketches showing the depth of the seabed and the contours of the islands. We reach the Mutton Cove anchorage. Here we find the most beautiful lawn in Antarctica – a warm welcome! In fact, it’s moss and lichen that take advantage of the meltwater stream to grow on the rocks. It’s rare to see green on this continent of ice. Île d’Elle rests on the cliffside. Night is gradually returning. As the season progresses, the days grow shorter and darkness returns for a few hours at night.

As we sail off Renaud Island, I spot a red dot in the rock in the distance. Intriguingly, there are no (or very few) human traces here. We check it out with binoculars… it’s a huge pink buoy! According to Jean-Yves, it could have come off a fishing line. Pushed by the wind and currents, it would have ended up here, in a rocky fault. It catches the eye of our skipper, who sees it as a fine fender. We, on the other hand, see the buoy as a big piece of plastic waste. So we launch the dinghy. I take the helm of the dinghy in full view of the crew on board. It’s a hard collision, and I rush Jérémie ashore and watch from the dinghy as he struggles with the big pink bubble. It’s much bigger than expected: at least 1.30 m high! Proud of our rescue, we hoist the buoy aboard and, under the captain’s orders, deflate it to keep it off the deck. It briefly became a superb footstool for observing the drifting ice and will certainly be exchanged or sold on our return to Ushuaïa.

After a month at sea, we finally reached Marguerite Bay, having made our way through a tiny gateway into the ice-covered funnel-shaped rocks that sailors call the “Narrows”. But Antarctica was hot again this year. The Narrows didn’t even freeze over this winter. The year 2022 saw a new and sad record: the extension of the southern pack ice reached its lowest point since satellite records began, falling below 2 million square kilometers for the first time. This fragility, this precious nature of the life that unfolds here, in this realm of ice, is something I had only scratched the surface of on my first visit to Antarctica. This return to Antarctica by sailboat did more than give me time to contemplate all this splendor. It definitely opened my eyes to the importance of doing everything in our power to preserve them.

Find out more about our awareness-raising initiatives on the Polar Witnesses Endowment Fund andÉcole des Pôles websites, as well as my virtual reality film Marins des Glaces, co-produced with VisionR, and the film L’Île d’Elle, directed by Hubert Lagente.